Looking for a specific blog post or topic? Search below.

Friday springtime vibes in this classic image by photographer Constance Stuart Larrabee, ca. 1950. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Waterman’s shanties in Dorchester County, Maryland, ca. 1941. Collections of the Library of Congress.

Springtime means flood tides here in the Chesapeake, both today and historically. These images from a waterman’s community in Dorchester County, Maryland, in 1941, show that flooded fields, catwalks above drowned yards and an unclear distinction between water and land are nothing new.

What has changed is that these flood tides are now no longer relegated to spring. Dorchester County barely skims above sea level- it the second lowest county in Maryland and one of the lowest in the United States- and because of that, it experiences the ravages of high water and the prevailing winds across the Bay more intensely than anywhere else in Maryland. Today, flooding happens year-round, and along with impassable roads and submerged cars, whole stretches of the shoreline are steadily eroded by the ceaselessly encroaching waves of the Chesapeake.

The loss of land is particularly acute on the islands the lie offshore of Dorchester- Hooper’s, Holland, and Bloodsworth, where more than 20 acres a year disappear into the Bay. In many of these communities, residents have attempted to protect their homes by armoring their shorelines or jacking up their houses. Many have been forced to leave all together.

For Dorchester County’s maritime towns, the lives of watermen and their families have have long been dictated by the cycles of the Bay. But unlike 1941, when a springtime flood muddied boots and flooded yards, modern Chesapeake towns suffer tides that come seasonlessly, threatening their homes as well as their livelihoods.

“The Washington Navy Yard, With Shad Seines in the Foreground.” Harpers Weekly, 1861. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Spring has historically meant the beginning of one of the Chesapeake’s most significant harvests- shad. This “founding fishery” marked the beginning of large-scale commercial fishing in the Bay, in the mid-1700′s. Unlike oysters or crabs, which required canning and refrigeration (not invented for another 75 years), shad could be preserved just by being salted and dried. As many tobacco plantations switched to wheat, the time saved by the less-laborious crop meant that many waterfront estates began to use their slave labor to harvest shad as another way to make money.

Shad remained a vital industry in the Chesapeake well into the 20th century. This image, from Harper’s Weekly in 1861, shows the traditional spring shad seine harvest on the shoreline of the Potomac. In the background is the Washington Navy Yard, depicted as tidy and efficient (a quintessentially Victorian love of industry), and beyond that, the skeleton of the Capitol Building, still under construction.

Chestertown, Maryland’s 2016 Downrigging Festival was a beautiful fall weekend for celebrating the most beautiful wooden boats on the Chesapeake Bay. Whether local ladies like the Sultana or the Elsworth, city girls like the Pride of Baltimore or the Sigsbee, or vessels from further afield like the Kalmar Nyckel, the ships are stacked up on the dock sometimes two-deep to allow visitors from around the country the chance to see and sail on these magnificent craft.

It’s an event that marks the end of the tall ship season on the Chesapeake- and afterwards, many of the buyboats, bugeyes, schooners and clippers return to their home port to be unrigged, hauled and worked on over the winter. With fireworks, bluegrass, and some stately trips down the Chester River, thousands of people celebrate the year’s last hurrah for these charming watercraft. Hulls gleaming and flags standing proud in a warm fall breeze, they are reminders of a time not so distant when these ships were the Bay’s most essential connection between small Chesapeake towns and a vast maritime world.

It’s a past worth celebrating- and a beautiful one, at that.

Images by author. All rights reserved.

River Schooling

Students onboard the school skipjack Elsworth at sunset on the Chester River. Photo by author.

Throughout the Chesapeake when the weather is fair, wooden vessels are plying their trade—but it isn’t shellfish they’re capturing, or finfish, or even blue crabs. Rather than bushels of the Bay’s bounty, their decks are awash in kids. These are the Chesapeake’s school ships: once built for working the water, they are now floating classrooms, taking out school groups to experience that old Bay magic, up close and personal.

It’s a trend that’s extended to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, with the buyboat-turned-educational-vessel Winnie Estelle, to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and their skipjack Stanley Norman, and to Living Classrooms onboard the skipjack Sigsbee and the buyboat Mildred Belle. These beamy working beauties, so perfectly adapted to Chesapeake waterways, provide the perfect space for learning on the water— and as modern watermen turn almost universally today to fiberglass vessels, it’s a second chance at life for these traditional Bay boats that might otherwise have ended up as just another rotting hulk in a remote Bay marsh.

A fine day for exploring the Chester with a full class of students onboard the Elsworth. Photo by author.

The skipjack Elsworth is one of these Chesapeake river school boats. Owned and operated today by Echo Hill Outdoor School, she was originally built in 1901 in Hudson, Maryland on a tributary of the Little Choptank River— ground zero of the Bay’s historic oystering industry. After a long career of oystering, the Elsworth was acquired by Echo Hill in 1988. For the next eight years, she continued to work for her keep, taking students out in the warm months and then dredging during the “r” months to earn the funds needed to pay down the loan for her aquisition. In 1996, after almost a decade of working the Bay’s oyster bars for Echo Hill Outdoor School, she was rebuilt and re-purposed as a purely educational vessel.

Captain Andrew McCown in his element. Photo by author.

The mastermind behind this successful gambit and the man who captained the Elsworth during those hard dredging winters is a passionate educator, conservationist, and all-around Chesapeake environmental expert— Captain Andrew McCown. A native of Kingstown, Maryland, just across the Chester River from Chestertown, McCown has dedicated his life to inspiring learners of all ages with the Bay’s environment, culture, and traditions. McCown’s father was a dedicated outdoorsman, and as a boy, McCown grew up fishing, hunting and exploring the dense marshes and hardwood uplands of the Chester River. These simple experiences would be so elemental to McCown— yet as an adult, he found fewer and fewer of the children he encountered could share them. The solution would become Echo Hill Outdoor School, founded in 1972 by Peter Rice, where McCown and a team of environmental educators could introduce children to the marvelous magic of quiet Bay coves, the cathedrals of old growth forests, and the freedom of wet, muddy and entirely hands-on outdoor learning.

A bevy of wooden-workboats-turned-school-vessels rafted up on the south Chester River. Photo by author.

Throughout the spring, summer, and fall, the Elsworth is joined in her on-the-water learning experiences by several other wooden Chesapeake craft in the EHOS fleet—the buyboat Annie D, two 20th century workboats, Spirit and Twilight and two bateaux, the Ric and the Mr. Lewey (both named after seminal characters in Gilbert Byron’s classic book, much beloved by Capt. Andy, “The Lord’s Oysters.”). These six vessels are deployed throughout the fine months to ferry students to the heart of the river action—the best holes to seine for silversides or to cast a line to maybe hook dinner, the muddiest gunkholing spots, quiet places where the purple spikes of pickerelweed attract the tiny jewellike bodies of mating damselflies.

Students from Washington College join EHOS Captain Annie Richards in an

up-close-and-personal look at watermen pound netting on the Chester

River. Photo by author.

These are not chance destinations— rather carefully chosen Chester River classrooms, where students can encounter the wild beauty of the outdoors and educators can shape meaningful environmental experiences. A morning trip after sunrise to a poundnet becomes a discussion about sustainability, watermen, and invasive species, and Capt. Andy holds up a diamondback terrapin he plucks from the net announcing, “I think this is the most beautiful turtle in the Chesapeake.”

He means it. As

your bateau bounces on the chop and the students around you push to get a

better view of the turtle or the watermen, there isn’t a shred of irony on this little wooden workboat. Capt. Andy is genuinely passionate about

the turtle in his hand and the watermen we’re watching, and every student is

too. Pure unadulterated enthusiasm, you understand, is a powerful teaching

tool.

Students enjoy a lunch crab feast of fat river crabs, and best of all, no need to worry about clean up. Photo by author.

Powerful, too, is the unfettered sense of freedom on these Chester River expeditions. Instead of cafeteria lunches, crabs, caught in the morning as the sun rose, are eaten for lunch directly from the bushel basket and cracked on the Elsworth’s broad decks. School uniforms are exchanged for old tee shirts and shorts or even better, bathing suits. And rather than paper, pencils, and books, students are encouraged to learn with their hands, their eyes, and and by making real-world connections— meeting watermen, raising sails, swabbing decks, and catching crabs. The study the ecosystem by literally immersing themselves in a marsh, as an environmental educator discusses the plants, animals, fish and insects they see. There is learning going on constantly, but it feels like play— the kind of play Andrew McCown so vividly recalls from his childhood on this same Chesapeake tributary.

The Mr. Lewey takes McCown and a few students out to explore the evening river. Photo by author.

A bluebird day of active environmental education ends with a audacious sunset, a repast of fried fish caught by students that afternoon, and possibly a quick trip out in one of the bateaux to cast one last line before last light. As the students settle into sleeping bags on the deck of the Elsworth, McCown, Captain Richards, and crewmate Aaron Thal pull guitars and a ukelele from belowdecks. Together they put on an inpromptu concert, singing Chesapeake-inspired songs and reading river-inspired poetry as a million stars slowly coalesce into a white river overhead mirroring the dark one lapping at the hull. “My sweet heaven on the Chester,” McCown sings in his fine voice, and the students onboard drop slowly onto pillows, to rest for another challenging day at outdoor school.

My thanks to Andrew McCown, Annie Richards, Aaron Thal, Echo Hill

Outdoor School and Washington College for the opportunity to join an

overnight educational program onboard the Elsworth.

A neighborhood crab house in Baltimore in the 1930′s wasn’t exactly what we expect of our modern crab establishments. The “house” part was often quite literal- proprietors were frequently women who ran a crabcake and clamcake business out of their kitchen, or in this case, their front window. Customers, lured in by the smell of fried things wafting on the breeze, could plunk down a few nickels, pull up a patch of curb and demolish a perfectly golden, perfectly greasy crabcake, right on the spot.

Though the venues may have changed, the ritual of a summer crabcake is deeply ingrained in Chesapeake tradition. Served between two slices of white bread, it is a taste of the Bay that conjures nostalgia, comfort, and the humid pleasures of a July afternoon in Baltimore.

From the Library of Congress, by “Look” magazine photographer John Vachon, 1938.

“There is but one entrance by Sea in this County, and that is at the mouth of a very goodly Bay, 18 or 20 myles broad…. Within is a country that may have the prerogative over the most pleasant place ever knowne, for large and pleasant navigable Rivers. Heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man’s habitation…Here are mountains, hills, plaines, valleyes, rivers, and brookes, all running into a faire Bay, compassed but for the mouth, with fruitfull and delightsome land.” -Captain John Smith, 1609.

Image by Kate Livie. All rights reserved.

Calvert Cliffs

Fragments of fossils at Calvert Cliffs. Image by author.

Just north of Solomons, Maryland, at the narrowing middle of the Chesapeake Bay is a treasure hunter’s wildest dream. Open to the public and free of charge, anyone with a will and a sieve can sift through soils of sand and clay at Calvert Cliffs, searching for sign of life from millions of years ago.

The massive, iconic cliffs were first documented by Captain John Smith during his 1608 exploration of the Chesapeake, who named them after his mother’s family. Leaving the Hooper Strait north of Bloodsworth Island, Smith wrote, “…we passed by the straights of Limbo, for the

weasterne shore. So broad is the bay here, that we could scarse

perceiue the great high Cliffes on the other side. By them, wee anc[h]ored that night, and called them Rickards Cliffes.”

Smith did not explore the cliffs in detail, and makes no mention of the feature that draws thousands of visitors to Calvert Cliffs each year— the incredible artifacts concealed within cliff face that slowly erode from the iron-stained soil. Shark’s teeth, scallop shells, snail shells and dinosaur bones emerge with heavy rains or high tides, evidence of the shallow sea that existed here during the Miocene epoch 20-3 million years ago.

Calvert Cliffs. Images by author.

During the Miocene, the Chesapeake as we know it today didn’t exist. Instead, most of the modern watershed was covered by a warm, shallow sea, known as the ‘Salisbury embayment.’ Within the sea, enormous sharks, turtles, crocodiles and other marine species thrived. On the land surrounding this ancient brackish water bay, an incredibly diverse spectrum of mammals from hippopotamus to mastodons roamed open grasslands and deciduous woods.

As these creatures eventually shuffled off the mortal coil, they left behind copious deposits of their bony remains that were entombed over millennia in sand or clay soils. They remained there until 18,000 years ago. When the glacial melt from the last Ice Age began to form the Susquehanna River Valley- the precursor to the Chesapeake Bay- the icy flow eroded the ancient sea floor. As the modern Chesapeake continued to emerge, the brittle Miocene artifacts were exposed.

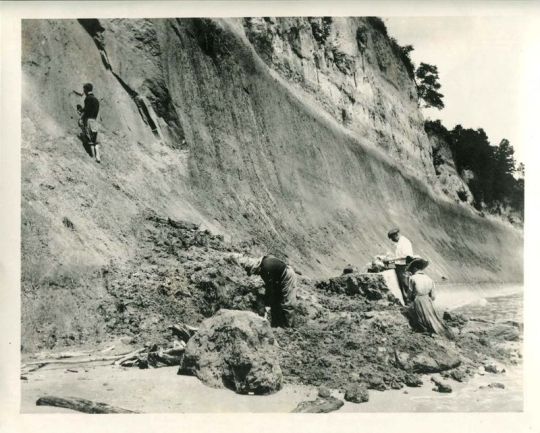

Members of Smithsonian Institution collecting fossils at Calvert Cliffs, summer of 1908. Courtesy of the Calvert Marine Museum.

Where there are fossils, there are fossil hunters, and Calvert Cliffs have been frequented by scientists (both credentialed and that of the armchair variety) for over a century. W.F. True, a palenontologist at the Smithsonian in the early 20th century wrote of one expedition to the cliffs in 1906, “Weather dull, but cleared at noon…Left a large number of vertebrae and

some fragments of jaws etc., along the cliffs, as could not carry so

many.” Since then, many have followed True’s path along the cliffs, searching for the latest treasures to be liberated by rain, wind, or water. The nearby Calvert Marine Museum has an extensive exhibit dedicated to some of the most spectacular discoveries by paleontologists over the years— but true to the open-access spirit of the Cliffs, the museum also provides a free ‘paleontologist on call’ service for amateur fossil hunters who need help identifying their treasures.

Fossils at the Calvert Marine Museum.

Treasure hunting at Calvert Cliffs State Park. Image by author.

There are several sites along Calvert Cliffs that are open to the public and welcome fossil hunters. Bayfront Park, Calvert Cliffs State Park and Flag Ponds Nature Park all provide some access to the cliffs and allow visitors to take home their finds (more info here). Although not every visit yields a truly rare find, it’s a great way to explore a wonderfully weird aspect of the Chesapeake toothier, more primal past.

A common sight on rivers during the midsummer around the Chesapeake Bay— pound nets. Used to trap fish, pound nets are one of the oldest gear types used by watermen in the Chesapeake. Made up of a stout poles strung with netting to create a series of funnels, pound nets can catch and hold thousands of fish once they’re constructed. Native Americans along the Bay had their own version of pound nets known as “weirs,” which closely resembled the gear used by modern watermen. Herons, osprey, eagles and other fish-loving birds of prey are often thickly settled on the pound nets, poles and trees nearby— anything that will get them closer to the fish that seethe within.

Image by author.

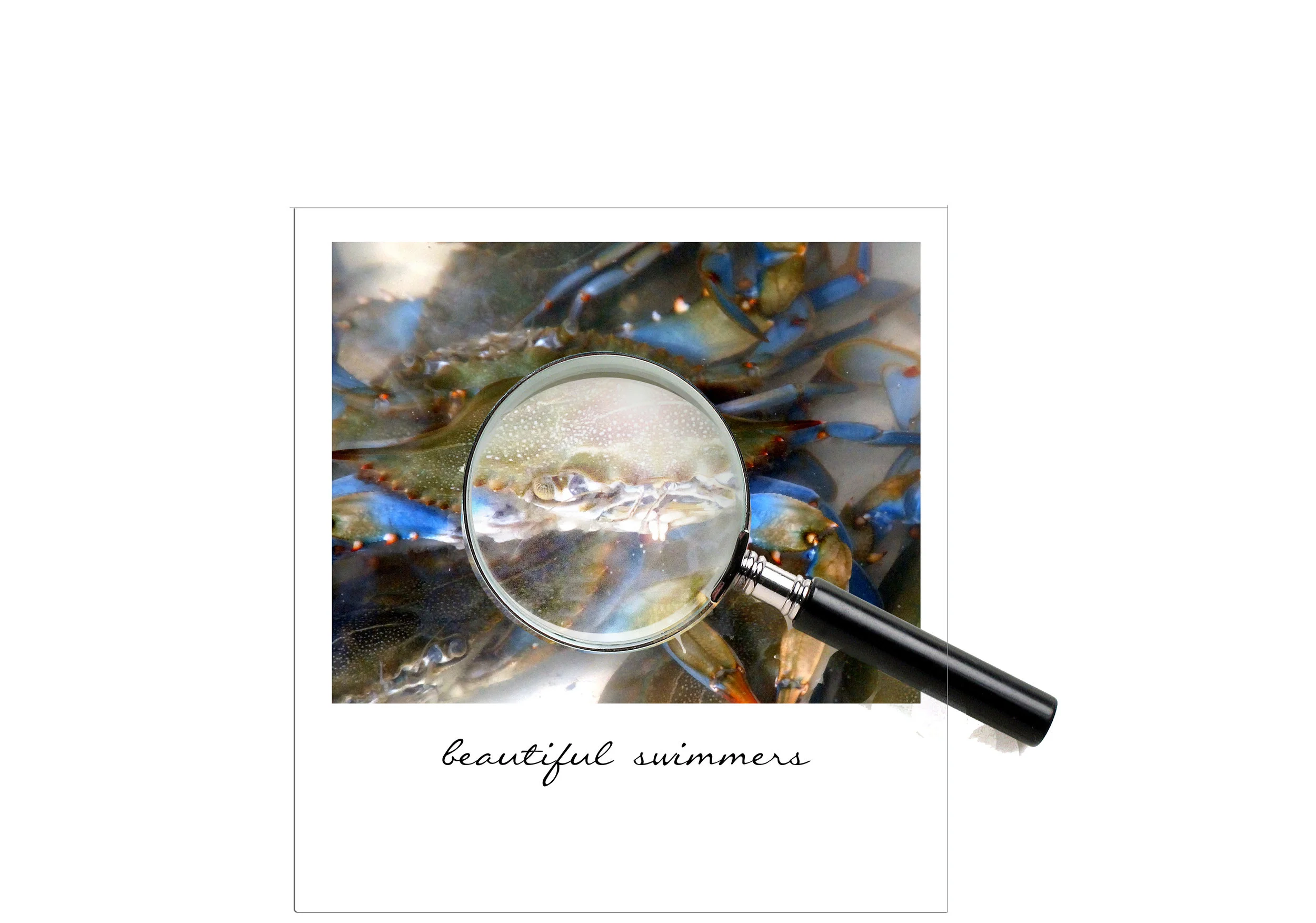

Oh yeah, it’s on. Higher temperatures at the end of May have brought on the full flush of the Chesapeake’s blue crab bounty. From now until first frost, the crabs will only get fatter- good news for anybody who loves a Sunday spent at a picnic table with an ice-cold beer and a pile of these delicious monsters.

19th century postcard depicting Baltimore Harbor, with the steamboat Chester in the center of the image. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

On this day, May 31, in 1872, a Chesapeake steamboat was the object of one of the earliest pre-Jim Crow cases in Maryland. Josephine Carr, an African-American school teacher from

Kent County, sued the steamboat Chester for an assault. The incident

had taken place on May 14, when Carr sat in the steamboat’s main cabin- a space reserved for white passengers. When Carr refused to

move, the captain and crew dragged her to the black-only forward cabin, where Carr declined to wait. Instead, she moved to the bow, where she stood until the Chester reached Chestertown and Carr disembarked. She would later file a libel suit against the Chester for her mistreatment.

Carr won her landmark case, and was awarded $25 damages. Carr’s case was one of several

in which 19th century courts ruled in favor of blacks on

transportation accommodations- a precursor to many such standoffs, which Rosa Parks would someday make famous.

Solomons Island, Maryland

Aerial view of Solomons Island, Maryland. Photo by author.

About halfway down the Chesapeake Bay’s main stem, where the Bay narrows to a blue band flanked by cliffs and marshy islands, the small town of Solomons protrudes into a bend at the mouth of the Patuxent River. Occupying a fishhook-shaped island of white churches, prosperous 19th century homes, a long promenade, bustling shops, and a signature museum, Solomons is a place that seems to have effortlessly transitioned from working waterfront town built on the oyster industry to a modern mix of savvy commerce and tourism seasoned with a deeply Chesapeake flavor.

Stained glass window at St Peter’s Episcopal Church, Solomons Island, Maryland. Photo by author.

The maritime roots of the town are clear. Cheek to jowl with the Patuxent River, local churches bear stained glass decorated with boats, not saints. Docks protrude like piano keys into the river. Adjacent to the long promenade, small runabouts are moored under the gentle curve of the Johnson bridge. Marinas, tiki bars, the Calvert Marine Museum and a nearby Naval Air Station all emphasize the commercial, educational and strategic importance of Solomons Island’s endless waterfront.

Sunset at Governor Thomas Johnson bridge, Solomons Island, Maryland. Photo by author.

Drum Point lighthouse at the Calvert Marine Museum. Source

Solomons Island seems remote today, when urban centers are the locus around which populations congregate. Historically, however, it was located adjacent to one of the richest oyster troves in the entire Chesapeake Bay. Alternately called “Bourne’s Island,” “Somervell’s Island,” or “Sandy Island,” from the 17th century through the 19th century, it was the name of the Baltimore entrepreneur Issac Solomon—who established a major oyster cannery on the island after the Civil War—whose moniker stuck. Solomon was a major investor in the island. He initially purchased 80 acres for his oyster cannery, worker’s housing, and support buildings. Solomon also invented a rapid sterilization process that allowed packinghouses to increase their production from 3,000 cans a day to 20,000- a boom that allowed packers like Solomon to turn an enormous profit. Thanks to this jump in production, the Solomons’ fishing fleet reached 500 vessels by 1880, and the little island boasted fine Victorian homes and a businesses all supported by the vast infusions of oyster money.

Solomons Island, ca. 1920. Images from the Library of Congress collections.

JC Lore Oyster Packinghouse, Solomons Island, ca. 1970. Image from the Library of Congress Collections.

Today, the J.C. Lore Oyster House is all that remains of Solomons’ oyster heyday. Now part of the Calvert Marine Museum, it represents the 60 year pinnacle of the Chesapeake’s once-might oyster fishery and the prosperity it brought to waterfront communities like Solomons Island. But while the decline of the oyster and crab industries spelled ruin for other maritime towns, Solomons’ story wasn’t over yet. World War II saw Solomons Island chosen as a staging area for amphibious invasion training. Between 1942-45, the population on Solomons Island grew from 263 people to more than 2,600— all of them requiring homes, utilities, stores and services. It shepherded in the next era of good fortune into the little island, which wasn’t so little anymore.

J.C. Lore Oyster House, Solomons Island, Maryland. Photo by author.

Today, Solomons Island, despite many transformations remains waterbound, bustling, and full of Chesapeake charm. Watermen still work on the river, and locals crowd restaurant patios on fine summer evenings. Built on its past, like a packinghouse on oyster shells, it sits at the tideline, timelessly.

For more information on Solomons Island:

Book explores history and future of Chesapeake Bay oysters

Kate Livie, director of education at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, is a champion of Tidewater Maryland’s culture and heritage.Her book, “Chesapeake Oysters: The Bay’s Foundation and Future,” recently published by American Palate, a division of History Press, couldn’t be more timely, as oystermen, scientists and state governments continue to grapple over what is the best way to manage, preserve and increase the bay’s bounty of Crassostrea virginica, better known to connoisseurs as the eastern oyster.

Gilbert Byron’s original tiny house

The Gilbert Byron house, the home of “the Chesapeake Thoreau,” image by author.

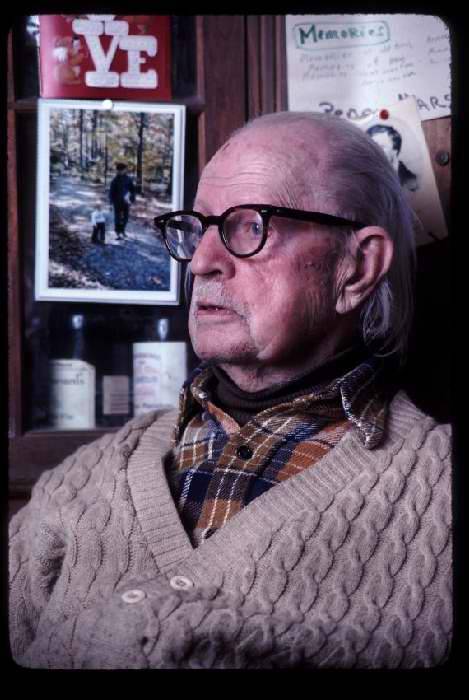

Writer Gilbert Byron

lived alone in this cabin for nearly 45 years on San Domingo Creek’s

Old House Cove. Within its three rooms, which he built himself, Byron crafted short stories and poetry, all inspired by the

people, places and landscapes of the Chesapeake Bay. A prolific writer

of the late twentieth century, Gilbert Byron published 14 books and 70

short stories, articles and poems during his writing career, and most were composed here.

Gilbert Byron. Photo by Tyler Campbell, shared with permission of the Kent County Historical Society.

Byron was a native of Chestertown, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, and much of his work is set along the Chester River where he grew up and the lower Eastern Shore where he spent his adult life. Lyrical, keenly observant, and deeply steeped in place, Byron’s work reflects the end of the Bay’s era as the great highway and the great divider. His stories are inspired by a Chesapeake when rivers were roads traversed by steamboats and log-built descendants of dugout canoes, plied by hardy people Byron referred to as ‘elementals’— watermen and farmers who lived close to the land and closer to the water.

Image by author.

After his death in 1991, Byron’s modest

cabin, truly the original ‘tiny house,’ was preserved thanks to the

efforts of several Talbot County organizations. Relocated from its

little cove outside of St. Michaels and restored in commemoration of

Byron’s life and work, Byron’s cabin now resides at Pickering Creek

Audubon Center. It can be visited by the public for free, and once you lift a hook on the door, you’re free to explore the diminutive rooms that Byron built himself and imagine him gathering inspiration from the view over his beloved placid little cove.

Images by author.

A low sun turns/ Chesapeake’s yellow cliffs/ Into golden hills/ Stillness finds the evening/ calms the water/ And my spirit/ Joyous fish leap/ From the cooling river,/ The peepers whistle/ To the greying marshes/ In the darkening skies/ A passing heron cries/ A falling leaf/ A cowbell far away/ That flitting bat/ From night itself/ Ushers out the day.

“Chesapeake Evening” from The Wind’s Will by Gilbert Byron, 1940.

For more information on Byron’s work and life, the Gilbert Byron Society is an excellent resource: www.gilbertbyron.org

Signs of spring- menhaden are moving into the Bay. This time of year, the water clarity is excellent- providing a clear view to the massive, undulating schools.

Menhaden are often found at the top of the water column near the surface, where, as filter feeders, the gape-mouthed fish will devour copious quantities of both plant and animal plankton.

Menhaden are essential to the Chesapeake food chain, both digesting plankton and in turn feeding predators, whether birds or large fish species. Although fears of over-fishing have been widespread given their critical role in the estuary, today the fishery is well-managed and stable- good news for a species critical to the Chesapeake’s environment.

For more information on menhaden: http://1.usa.gov/25nnC3a

Image by author. All rights reserved.

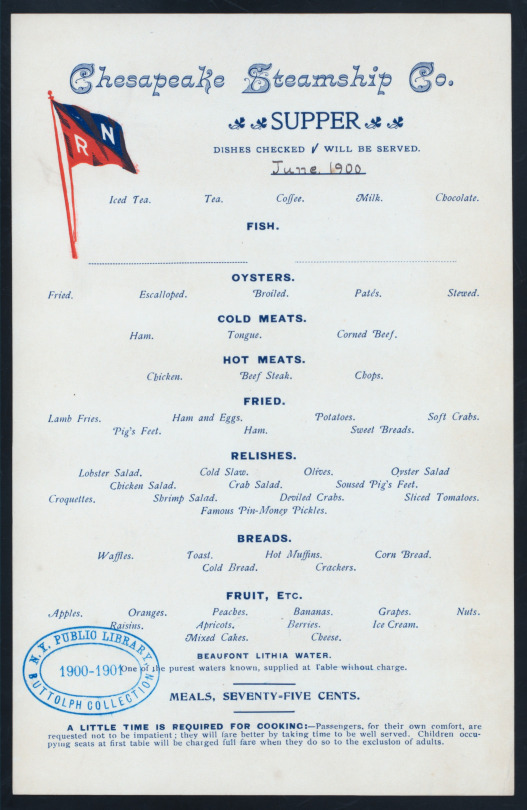

Savoring the Bay Through Historic Menus

1901 Breakfast menu from the Hotel Chamberlin at Old Point Comfort, Virginia. Collections of the New York Public Library.

Like the rest of the online world, we at CBMM have spent our time virtually plundering the treasure trove that is the New York Public Library’s newly digitized online collections. Over 674,000 items have been scanned and uploaded, for anyone to enjoy, and the site is full of thousands of rabbit holes to descend into, delightfully. One such rabbit hole is the Buttholph collection of menus, which encompasses almost 19,000 pieces of restaurant ephemera from 1843- 2008.

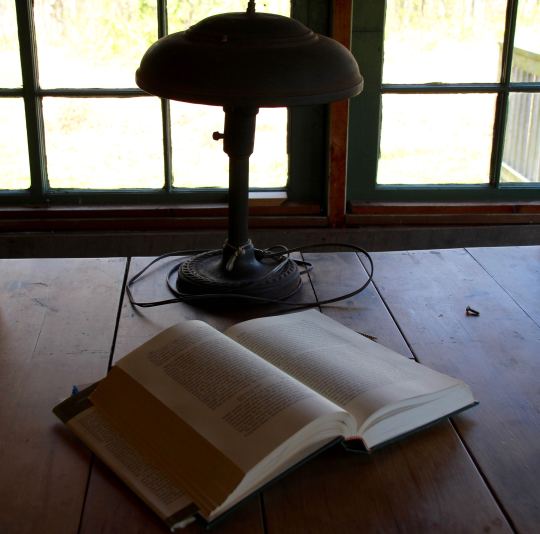

Princess Anne Hotel menu from Virginia Beach in 1897. Collections of the New York Public Library.

The menus have been sourced from around the country, and the Chesapeake examples are particularly delightful. The strong representation of seasonal harvests is clear, from the planked shad and oyster fritters served up at the Princess Anne Hotel to stewed oysters and clam broth (for breakfast, no less!) on offer at old Point Comfort’s Hotel Chamberlin.

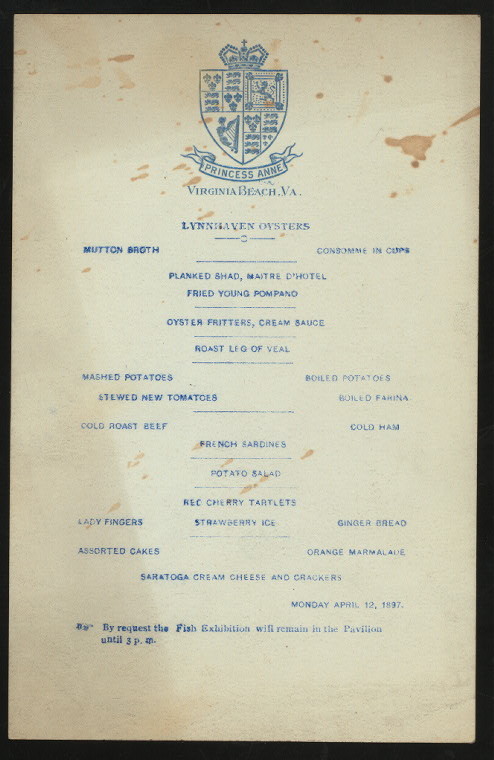

1900 Supper menu from the Chesapeake Steamship Company. Collections of the New York Public Library.

White tablecloth service and the Bay’s bounty weren’t only available on land, however- Chesapeake Bay steamboats were renowned for their elegant meals and world-class service. Diners enjoyed their sumptuous repasts in lavishly paneled dining rooms under crystal chandeliers, and tucked in real linen napkins at their collar. Liveried waiters brought courses of oyster pate, tongue, pig’s feet, pin-money pickles, and other substantial fare for the reasonable price of seventy-five cents.

1901 Baltimore Masonic Temple menu. Collections of the New York Public Library.

The menus also indicate that both citified and country folks alike savored meals built around the ample harvests sourced from the Chesapeake Bay- many of which are illegal or restricted today. Shad, for example, was a popular 19th century dish that has been a closed fishery in Maryland waters since the 1980′s due to low populations. Green turtle soup, made from sea turtles harvested at the mouth of the Chesapeake, is another example of bygone fare- the species is now endangered, largely due to harvesting for that very dish.

These fascinating examples of Chesapeake material culture are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg in the New York Public Library’s digital collections- where carefully-saved documents create a paper trail that leads us right to the Chesapeake’s rich, delicious past.

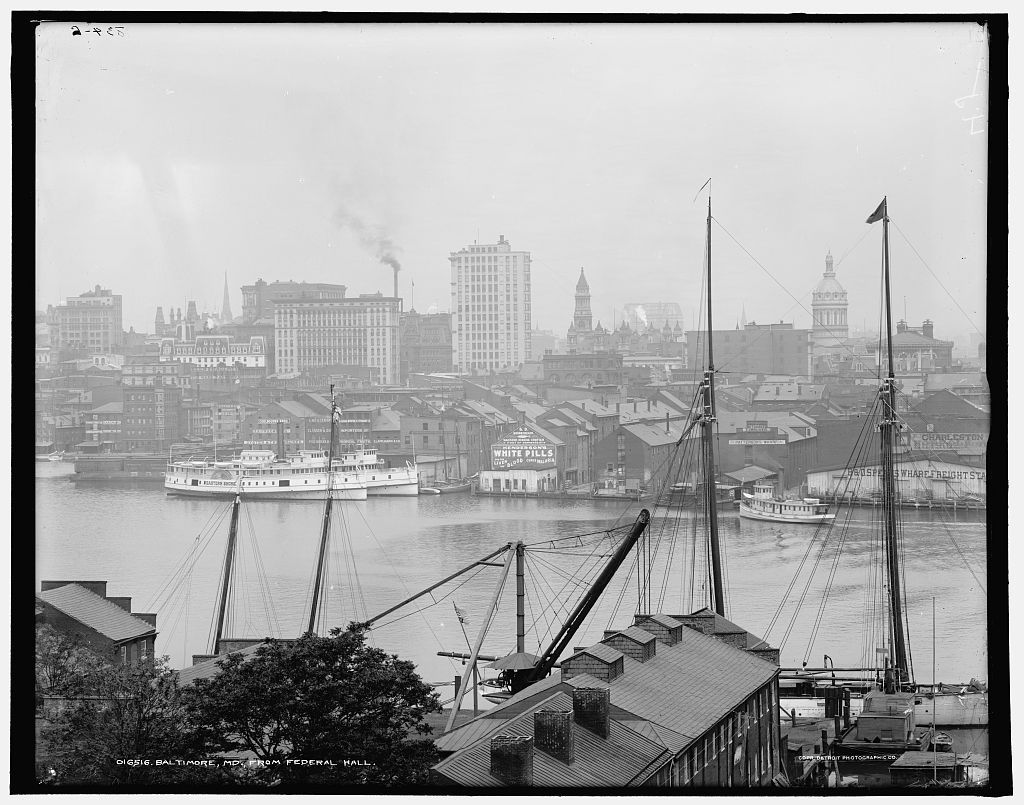

(top) Baltimore harbor from Federal Hill, 1850.

(top middle) Baltimore harbor from Federal Hill (facing Fell’s Point), 1870.

(middle) Baltimore harbor from Federal Hill, 1902.

(bottom middle) Baltimore harbor from Federal Hill, 1948.

(bottom) Baltimore harbor from Federal Hill, 2014.

These five images show the dramatic transformation of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, all taken from the vantage point of Federal Hill. From the 1850′s, when the city had just started to feel the impact of the Industrial Age, to the 1870′s, when oyster packing filled the harbor with skipjacks and bugeyes, to the early 20th century, when the last of the steamboats plied their routes throughout the Bay, to today, when most of the traces of industry have been replaced by museums, malls, and leisure craft- Baltimore’s harbor has remained an essential element of Maryland’s largest city.

In our recent exhibition at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, “Broad Reach: 50 Years of Collecting,” one treasured item in our collections really stood out- a silent film, taken at the beginning of the 20th century, depicting what was then a series of quotidian scenes of steamboats arriving and departing from Chesapeake wharves. The filmmaker was a Washington, DC resident, Herman Hollerith, had a family home on Mobjack Bay.

The wealthy son of an inventor, Hollerith would later become one of the founders of the Norfolk and Mobjack Bay Steamboat Company after service to Mobjack Bay via the Old Dominion Line was ceased in April of 1920. He was also apparently a bit of a techie (as much as you could be in that era) and with his own hand-cranked movie camera, Hollerith set about capturing the everyday activities along lower Chesapeake wharves.

The product is astonishing- a turn of the century Chesapeake, captured like a moth in amber. These were the days so many old-timers fondly recollect, when the rivers were highways of commerce and of transportation, and the tiny communities they connected by steam were isolated enough to develop their own character. Even though the film lacks sound, it is still so incredibly alive- watermen use a hand-pump to bail their boat, a crewmen scrapes his supper off a plate, a gleaming thoroughbred hesitates before it boards the hold of a steamboat. Though much has changed about the Chesapeake since Hollerith made his little film, from the Bay’s boats to its occupations, it is reassuring that even today, the Chesapeake still occupies a central place for many along its tributaries.

A few of the many standout shots:

0:01 Unloading steamboat at rural wharf- Note that deckhand workforce is African-American

0:21 Loading thoroughbred racehorse

0:41 Steamboat General Mathews backing away from wharf

1:25 Deckhands loading barrels aboard in orderly succession

2:23 weighing fish—buying from watermen

2:58 bailing boat

3:21 Tug with railroad barge on the hip

3:33 aftermath of fire on General Mathews

• Burned March 22, 1930 at Norfolk Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company

4:23 steam Pilot boat and Hotel Chamberlin at Old Point Comfort

5:11 black deckhand handling a (heaving?) line

5:18 captain at starboard engine room telegraph

5:44 automobile exiting steamer

6:05 steamboat Annie L. Vansciver, built 1905 Camden NJ

6:14 back to Old Point & the plush Hotel Chamberlin

6:30 Annie L. Vansciver leaving Old Point wharf

6:50 large steamer with dark star on stack

7:12 sidewheel steamboat Annapolis, Built 1892 Baltimore as Sassafras (renamed when lengthened in 1902)

• Owned by Tolchester Beach Improvement Co, burned October 29, 1935

7:19 tug on C&D Canal

7:25 large motor yacht with crew clad in white on a dressed ship

7:43 lift bridge opening, possibly in Chesapeake City

7:55 tug with canal barge

8:27 motor yacht with white steel hull passing under lift bridge

“Tonging Skiff Gypsy Girl 7,” by Robert de Gast, collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

In this 1969 image, Tilghman Island waterman Ben Gowe gingerly follows the state icebreaker back to safe harbor after a day’s tonging during a cold snap. In icy winters, the state works to keep the Chesapeake’s principal channels open to navigation and deploys small icebreakers to help watermen return safely to port. Photojournalist Robert de Gast rode the icebreaker while documenting the Chesapeake’s oyster industry in 1969 and 1970 in preparation for a book, The Oystermen of the Chesapeake.