Calvert Cliffs

Fragments of fossils at Calvert Cliffs. Image by author.

Just north of Solomons, Maryland, at the narrowing middle of the Chesapeake Bay is a treasure hunter’s wildest dream. Open to the public and free of charge, anyone with a will and a sieve can sift through soils of sand and clay at Calvert Cliffs, searching for sign of life from millions of years ago.

The massive, iconic cliffs were first documented by Captain John Smith during his 1608 exploration of the Chesapeake, who named them after his mother’s family. Leaving the Hooper Strait north of Bloodsworth Island, Smith wrote, “…we passed by the straights of Limbo, for the

weasterne shore. So broad is the bay here, that we could scarse

perceiue the great high Cliffes on the other side. By them, wee anc[h]ored that night, and called them Rickards Cliffes.”

Smith did not explore the cliffs in detail, and makes no mention of the feature that draws thousands of visitors to Calvert Cliffs each year— the incredible artifacts concealed within cliff face that slowly erode from the iron-stained soil. Shark’s teeth, scallop shells, snail shells and dinosaur bones emerge with heavy rains or high tides, evidence of the shallow sea that existed here during the Miocene epoch 20-3 million years ago.

Calvert Cliffs. Images by author.

During the Miocene, the Chesapeake as we know it today didn’t exist. Instead, most of the modern watershed was covered by a warm, shallow sea, known as the ‘Salisbury embayment.’ Within the sea, enormous sharks, turtles, crocodiles and other marine species thrived. On the land surrounding this ancient brackish water bay, an incredibly diverse spectrum of mammals from hippopotamus to mastodons roamed open grasslands and deciduous woods.

As these creatures eventually shuffled off the mortal coil, they left behind copious deposits of their bony remains that were entombed over millennia in sand or clay soils. They remained there until 18,000 years ago. When the glacial melt from the last Ice Age began to form the Susquehanna River Valley- the precursor to the Chesapeake Bay- the icy flow eroded the ancient sea floor. As the modern Chesapeake continued to emerge, the brittle Miocene artifacts were exposed.

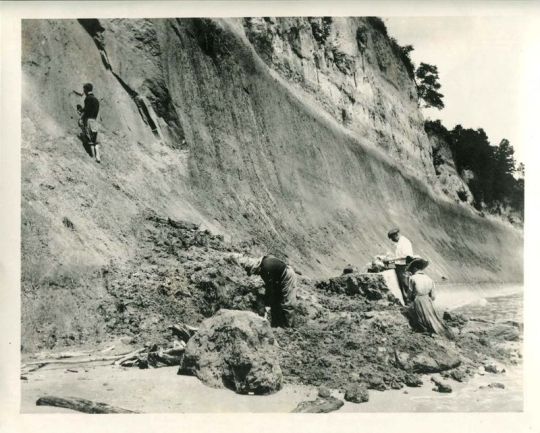

Members of Smithsonian Institution collecting fossils at Calvert Cliffs, summer of 1908. Courtesy of the Calvert Marine Museum.

Where there are fossils, there are fossil hunters, and Calvert Cliffs have been frequented by scientists (both credentialed and that of the armchair variety) for over a century. W.F. True, a palenontologist at the Smithsonian in the early 20th century wrote of one expedition to the cliffs in 1906, “Weather dull, but cleared at noon…Left a large number of vertebrae and

some fragments of jaws etc., along the cliffs, as could not carry so

many.” Since then, many have followed True’s path along the cliffs, searching for the latest treasures to be liberated by rain, wind, or water. The nearby Calvert Marine Museum has an extensive exhibit dedicated to some of the most spectacular discoveries by paleontologists over the years— but true to the open-access spirit of the Cliffs, the museum also provides a free ‘paleontologist on call’ service for amateur fossil hunters who need help identifying their treasures.

Fossils at the Calvert Marine Museum.

Treasure hunting at Calvert Cliffs State Park. Image by author.

There are several sites along Calvert Cliffs that are open to the public and welcome fossil hunters. Bayfront Park, Calvert Cliffs State Park and Flag Ponds Nature Park all provide some access to the cliffs and allow visitors to take home their finds (more info here). Although not every visit yields a truly rare find, it’s a great way to explore a wonderfully weird aspect of the Chesapeake toothier, more primal past.