Cool Things from Collections- the Poacher's Decoy

Just a few of our 10,000 treasures in our Collections Building at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

One of the most magical places here on our campus at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is the Collections Building. Tidily arranged on sterile-looking white shelves are a pirate’s horde of Chesapeake treasure: ship models and oyster cans, one-of-a-kind Bay boats from over 100 years ago, sail maker’s benches, steamboat menus, cork life jackets, the first Evinrude outboard motors, antique eel pots, and that’s just on the first row. Each object tells the story of some aspect of Chesapeake life or work, a talisman of a past Bay where the water represented sustenance, stability, and income.

A red-breasted merganser drake decoy, by Alvin Meekins, 1955. CBMM Collections.

Some of the the most interesting things in our collection are the most unexpected. As a maritime museum in the middle of the Atlantic Flyway, it makes sense that our collections would include decoys, as waterfowling is a big part of the Chesapeake’s unique heritage. Generally these are grimy, battered working decoys used for sport hunting, but there are a few decorative ones as well by big names like the Ward Brothers. Within that comprehensive collection of decoys there are a few surprises- like the merganser pictured above. These are working decoys, too, but these are special- created for use in the off season, or for birds that were illegal to shoot. They are examples of poacher’s decoys.

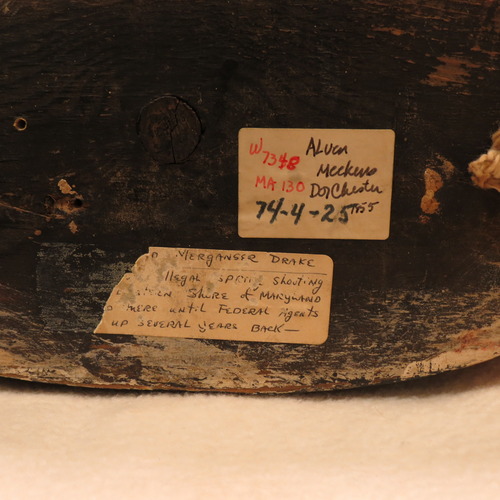

The bottom of the merganser, with a torn detail label.

This merganser drake decoy, made by Alvin Meekins of Hooper’s Island, Maryland, was confiscated at an illegal spring shoot in Dorchester County in the 1950’s, and both the decoy and its use are full of information about the Chesapeake’s environmental history. It was created during a ‘golden era’ of Chesapeake decoy carving, after the Migratory Bird Act of 1918 created limited seasons and shooting methods for waterfowl hunting.

Prior to that time period, there were very few limits to hunting at all, and those regulations that did exist were a patchwork of different limits, seasons, and rules that changed depending on which Chesapeake county you hunted in. Birds could also be baited, trapped, and shot on the water. There was no great need for decoys, which are primarily used in on-the-wing sport shooting.

With the new regulations in 1918, restrictions were federally placed on hunting, regulating seasons, limits, techniques, and locations. On-the-water shooting was eliminated, which suddenly made concealment and camouflage a necessity for anyone who hoped to get a shot at a bird in flight- and opened wide the market for decoys as key element of a waterfowler’s “gunning rig”.

Red-breasted Merganser detail- note the crest.

Decoys varied from river to river, reflecting the migratory birds that sought refuge in different parts of the Chesapeake. The northern Bay, the celery-grass-rich Susquehanna Flats in particular, were famous for canvasbacks, while the southern Bay was the winter home for a large variety of diving ducks.

Dorchester County, Maryland, where the merganser decoy was created, historically offered migrating waterfowl shelter in its expanses of salt water marshland and its reedy shallows, which teemed with small finfish. The mergansers, along with other fish-eating diving ducks, congregated by the millions in these open southern Bay tributaries.

But the drawback with mergansers is that they are what they eat- though filling, their flesh reeks of fish. This was no deterrent for the highly practical waterfowlers in Dorchester County, however, who merely piled the fishy duck on top of the muskrat and woodpecker that already filled their plate and had at it.

Similarly undeterred was the poacher who used this decoy for a spring shoot, several months outside of the winter hunting season. For many years after the waterfowling regulations went into practice, wardens had their hands full and their ears pricked for the sound of gunshots as they attempted to control the waterfowler’s longing to return to the limitless good ol’ days.

Delbert “Cigar” Daisey recalled poaching mergansers and avoiding wardens, “The bulk of the money I made back then was from trapping ducks. You just had to worry about the wardens. Hell, they knew all your traps and who you were selling to. I’d shoot mergansers, sometimes twenty-five to thirty-five a day from February to April, and then sell them to the people who worked in the oyster shucking houses. The good birds, black ducks and pintails, I’d sell to the other professional people during the week.”

As creative as poachers could be in attempting to skirt the law using decoys, baits, traps, or big guns(their backfiring homemade guns were truly works of eyebrow-scorching art), wardens were just as artful at catching them, as our out-of-season merganser proves. Wardens used boats, airplanes, dogs, and ingenuity to catch poachers, and our collections and exhibits have proof of their success, in decoy, gun, and photograph form.

It’s a lot of history in just one decoy, and its just one decoy in a row of hundreds in the CBMM collections, packed carefully away until their story gets a chance to be shared.