Getting to the Old Point

It’s the season of purpose for Old Point- built for winter use, it’s this time of year when the look of her, confined dockside and all her capability retrained, seems unnaturally harnessed. Old Point is a working girl, an example of a classic log built boat in the traditional style of vessel construction that owes its origin to the dugout canoes of the Chesapeake Indians, and was later adapted to the schooner form typical of 18th and early 19th century Bay vessels.

Old Point under restoration in The Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum’s working boat shop.

Sheathed within her hull are seven massive logs, weighty and substantial, creating a formidable backbone of strength and durability. Built in 1909 in Pequoson, Virginia, Old Point was intended to be a versatile workhorse, and when pressed to the primary task she was created for, Old Point weathered salt, ice, and bottom mud to harvest the lower Bay’s deep winter crab quarry.

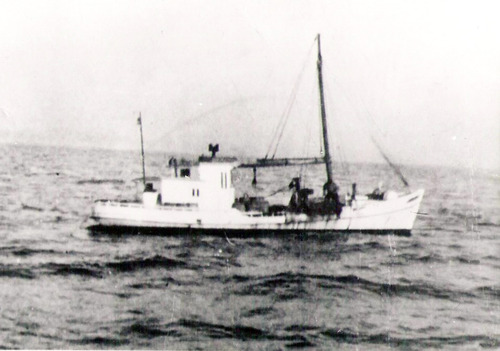

Old Point, dockside. Late 20th century.

Old Point was referred to in her heyday as a “deck boat”, but today we call her by the job she was built for- a “crab dredger.” Crab dredging was a technique for harvesting crabs in the winter, utilized by Virginia watermen. The idea takes advantage of the natural migration of crabs, particularly pregnant females, as they descend from the grassy shallows of the upper Chesapeake to the saline-rich water at the mouth of the Bay for the winter months, awaiting the fertile pulse of spring warmth. Huddled all winter long under a thick comforter of bottom mud, these females hardly move once settled and as a harvest are similar to other bottom-dwellers, like clams or oysters.

It makes sense, then, that the tool watermen traditionally used for crab dredging looks very similar to its cousin, the oyster dredge. Their heavier construction (almost double the weight of oyster dredges) is built for mud rather than oyster bars, and two dredges at a time are pulled in tandem behind the crab dredge boat. Their long teeth biting deep into the Bay’s cake-like bottom surface, dredges root out the slumbering female crabs in long curls of sediment, under which they might be insulated as thickly as six inches or more. A good “lick” might unearth as many as 3 to 4 bushels of crabs per pass. The loaded dredges are winched back onboard and deck hands cull through the frigid bay’s bottom detritus, seaweed, sponges, clams, and other bycatch, sorting the keepers into barrels destined for market.

It was grueling work; dirty, and brutally cold, but it meant a steady seasonal income when not much else was running in the wide open mouth of the Chesapeake, and a small industry flourished around the harvest. Old Point would be one in a fleet of ten to thirty dredgers leaving the safe confines the harbor in Hampton, Virginia, between December and March. The sequence of dredge scraping, winching, and culling would be repeated on each of the crab dredgers dozens of times a day multiplied by thirty, in search of their catch, deep under the mud.

Old Point in the early 20th century, with crew unloading barrels of crabs.

20 barrels was the catch limit per day, but many crab dredgers had trouble achieving that amount- but not because of the crabs. Captain Ben Williams, a crab dredger on the East Hampton recalled to author of Beautiful Swimmers (the book), William Warner; “What’s missing are the variables. There are many. Gale force days when dredging is impossible. Ice. The bitter cold when the crabs are so deep int he mud that nine or ten barrels is a long day’s catch. Loss or damage of dredges, which last no more than two years in any case, and consequent time for repair or replacement. Then there are those mornings when the captain finds an empty bed in the tiny pilothouse. A crew member has had enough, quitting without notice, and a dredge boat cannot operate with only one hand."

From 1913 to 1956, Old Point was owned by the Bradshaw family of Hampton, Virginia. They made a living working the water on her, not just in the cold months when the harvest was hibernating crabs destined for she-crab soup, but in all the other seasons too- hauling fish on ice in the summer, transporting oysters from the hand-tongers to the market in the fall. But it was a tight living, eking out of an unpredictable Bay enough money for food, clothes and housing for a growing family, especially during the Great Depression. In an interview, a relative of the family recalled Captain Bradshaw’s anxiety over the boat: "At the beginning of every season, he would have a sick stomach, and throw up, and for about a week or two, he would be worrying about the onset of the next change in his year’s work. …Just as soon as the fish running starts, he going to be fine. That would always be the case.”

CBMM shipwrights stepping Old Point’s mast, summer of 2010.

As the crab population dropped in the 1980’s, days were numbered for old crab dredgers like Old Point - one of the first restrictions put on the harvest to encourage a recovery specifically protected females, especially sponge crabs, which can potentially contain as many as three million eggs.

Old Point’s log-built construction was another issue. She was relic from an era when boats were built solidly, to stand the test of water, weather, and wind; a bit of a throw-back as plank-on-frame and fiberglass construction were the norm. When she changed hands and no longer had a captain that could maintain her, it became harder to find boat yards that could work on her- or had the materials, if they could haul her out. After she was sold to the Old Dominion Crab Company in 1956, that old-fashioned construction lead to a new-fangled and slip-shod fix- a fire in Old Point’s bow left a hole that was hastily filled with Portland cement.

Old Point, summer 2012, Eastern Shore of Maryland.

After a short stint as an excursion boat in the Caribbean in the 70’s, Old Point was finally donated to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in 1984, where much painstaking labor has been put into reconstructing her as she would have appeared as a raw-boned working girl from Virginia’s roaring twenties. Today, she is one of only two log-hulled deck boats to still exist on the Chesapeake. Like a whisper of fog flung out over a still creek, Old Point’s long lines evoke a chapter in Chesapeake history that is just barely visible in recent memory. Days when the sun burning over an icy Bay meant money and security. When crabs could be brought up from the salty depths of an angry Chesapeake in winter, culled by hand until barrels brimmed over with hundreds desperate legs, and finally turned back to port and warmth, seven logs holding the captain and crew safe above the whitecaps.