Headwaters

The mouths of rivers get all the love. They’re where you find watermen and pound nets, where it’s deep enough to swim and sail and maneuver a motorboat. They’re accessible and friendly and well-frequented.

But there’s a magic when you head upstream, an intimacy about the upper reaches of Chesapeake Bay tributaries. Shady, with still waters, these headwaters are remote and verdant. The houses built along the riverbank are far more modest than the stately homes found a few miles downstream, and sometimes just a few lawn chairs at favorite fishing hole are the only sign that people have been there at all.

Where rivers narrow, the chance at a close encounter with wildlife becomes increasingly likely. Herons squawk, outraged at being disturbed from their afternoon of fishing, and smaller creatures retreat into the underbrush, just slowly enough to be glimpsed.

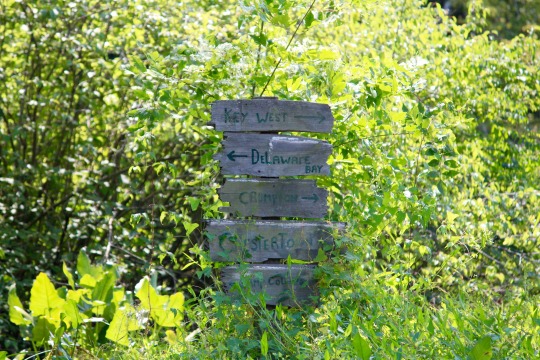

It’s easier than it might seem to get lost as you head upstream. Many small tributaries connect to the larger river main stem, and each small branch has its own charms. Some may conceal stands of blooming marsh hibiscus, or streams where the water is so full of Bay grass and so remarkably clear that you feel like 400 years have suddenly slipped away.

The vehicle of choice on headwaters is small paddling craft. Canoes or kayaks- vessels that can thread the exquisite, jewel-like streams and needle deep into the twisting switchbacks and oxbows. The slow pace lends itself to closer observation of the river. Plants, birds, and small mammals can be seen at close range when a kayak quietly approaches. It’s startling, how much bigger a small stream seems when you’re on eye level with the landscape. A rare river otter, breaching out of the pondweed just past the tip of your paddle, seems as large and hearty as a Chesapeake Bay retriever.

Headwaters are where much of the Bay’s life begins, from the shad that spawn on the shallow, gravelly bottoms to the slender elver eels that lurk under submerged tree trunks. Thick with plants, narrowed almost to a tunnel, these marginal areas for humans are vibrant habitat for many plant species, which riotously proliferate- milkweed, cardinal flower, wild rice, pickerelweed, tuckahoe. These, along with the submerged meadows below the waterline, act as filters, absorbing nutrients, contributing oxygen, and settling sediment that runs off the higher ground.

As summer winds down, the open waters of the Chesapeake will crowd on the weekends, as people fit in that last fishing trip, that last sail to Kent Island or St Michaels, or that last day to run the river on a jetski. It is the perfect season to turn upstream, and seek the solace of your river’s headwaters. Cicadas, damselflies and water bugs will herald your arrival as you approach the heart of the Chesapeake itself. A river’s beginning, located centrally in the absolute middle of nowhere.

All images by author. Many thanks to Chesapeake Semester at Washington College’s the Center for Environment and Society, who acted as guides for this trip up the northernmost part of the Chester River