Lost at Sea

From the cemetery at Cold Spring Church.

An article in the New York Times this morning explores the discovery of the Griffin, at 16th century French sailing ship lost in Lake Michigan and its reemergence from the sediments at the bottom of the inland sea. Headed by up a man arguably described as ‘obsessed’, this find has all the makings of a classic treasure hunt story- the devoted but slightly-crazed explorer, a ship full of treasure lost in mysterious circumstances, red tape, international intrigue.

Sunken ships and buried treasure are not sole property of the Great Lakes, or Outer Banks, or the coasts of Maine and Nantucket. The Chesapeake certainly has a slew of her own. Notoriously shallow, shoaled with sand and oysters, and difficult in which to discern bottom soundings, the Bay’s reputation in the 17th and 18th centuries was labyrinthine and deadly.

Scuttled WWI wooden steamship at Mallows Bay, Potomac River. source

According to Don Shomette, who worked for National Geographic in 2011compiling data regarding all known shipwrecks into a map, as many as 2,200 may exist as sand-covered ghosts on the bottom of the Chesapeake’s Bay. His results, published through the National Geographic Press as the Shipwrecks of Delmarva, document the lives and vessels lost forever to the Chesapeake’s capricious tides, wind, and weather. The tiny symbols that thickly pepper the map, each representing a sunken schooner or steamboat, is a reminder that the Bay is a treacherous place, regardless of its placid surface.

Closeup from the Shipwrecks of Delmarva map detailing wrecks at the mouth of the Patapsco River.

While many of the map’s shipwrecks are unidentified, there are plenty of famous wrecks, tantalizingly known and accessible- though the largest challenge to would-be treasure-hunters is the Chesapeake’s notoriously turbid water. Some of the most famous, like the Peggy Stewart, are also made memorable by the fantastic stories of their demise (burned by the owner to quell an angry mob, in that case). But even the less spectacular wrecks are getting attention, thanks to modern methods of bottom sleuthing, like side scan sonar. Amateur underwater archaeologists and hobbyist shipwreck seekers can combine historic charts and state-of-the-art technology to uncover vessels long obscured by thick black sediment, as exemplified by a recent post on Shawn Kimbro’s blog, Chesapeake Light Tackle.

Image from Chesapeake Light Tackle.

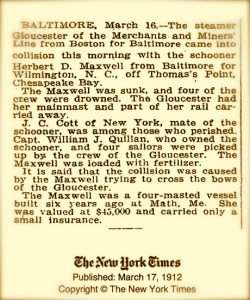

Kimbro dug into the historic background of a known shipwreck off of Sandy Point, the Herbert D. Maxwell. A four-masted schooner bound for Maine with a cargo of fertilizer, she was sunk initially in a 1910 collision with the steamer Gloucester that took the lives of four men. She was sunk again (or rather, deeper) by the US Army Corps of Engineers 1912, as her masts and other wreckage were blocking the shipping channel. Since then, she’s faded from view and memory, until resurrected in a series of spectral images by Kimbro’s side scan sonar unit.

Images from Chesapeake Light Tackle.

Like sepia photos in a shoebox, or discovering your grandma’s cache of cigarettes in a 30-year-old raincoat, these scans are tangible connections with a past that, as Faulkner once said, “is not even past.” It’s what makes them so fascinating- and in general, why we are so interested in shipwrecks. Time capsules, buried by sediment and protected the same water that ultimately drowned them, these vessels powered by steam, sail, and oar linger in brackish purgatory. Their treasure is rarely gold- more often, it’s detritus of a distinctly human scale- ivory toothbrush handles, copper coins, pierced lanterns, nails, canteens, and dice. They wait, lurk, dinosaur bones of a bygone era. Often nameless, these shipwrecks contour the Chesapeake’s bottom by the thousands- which means though many can claim knowledge of their whereabouts, the fresh excitement of new discovery is yours for the taking. All you need, it seems, is a decent depth-finder.