The James Adams Floating Theatre

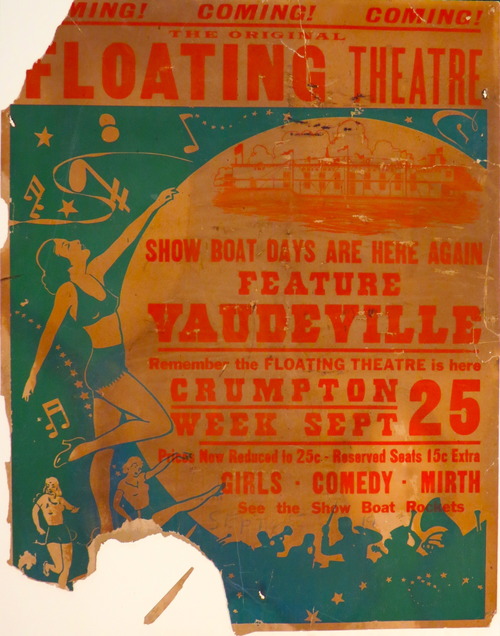

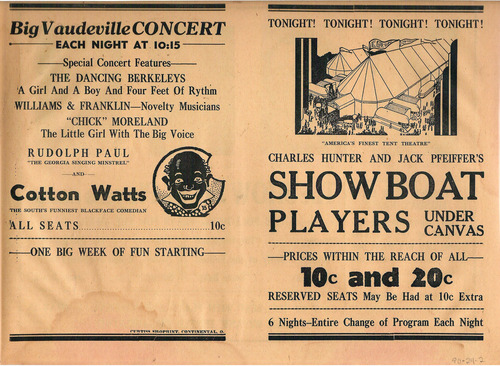

A “herald” for the James Adams Floating Theatre. Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

The posters came first. Screaming with gaudy colors and emblazoned with ladies emerging from a haze of stars and clouds with legs extended in a Jazz-Age salute, the imminent appearance was heralded: “Coming! Coming! Coming! Show Boat Days Are Here Again!"

Pasted on the walls of remote river towns in Maryland and Virginia, these visual whoops of excitement shared the news of the James Adams Floating Theater’s hotly anticipated arrival. In the deeply rural and isolated Chesapeake of the early 20th century, tidewater communities like Crumpton, Tappahannock and St Michaels were places where life revolved around seasonal cycles on the water and the land– tomatoes, peaches and crabmeat in summer, oysters, waterfowl and muskrat in winter. For Bay folk tethered to the river, it was a quotidian life, stable but utterly devoid of glamour. From Reedville to Chestertown, Chesapeake communities were starved for an infusion of glittery escapism.

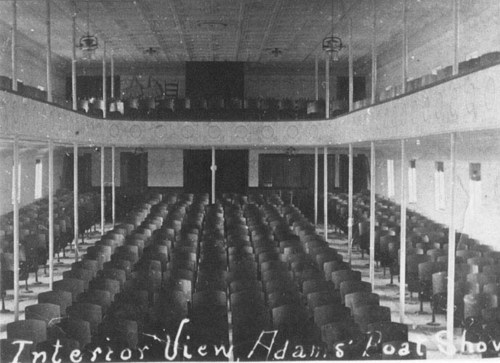

The Floating Theatre. Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

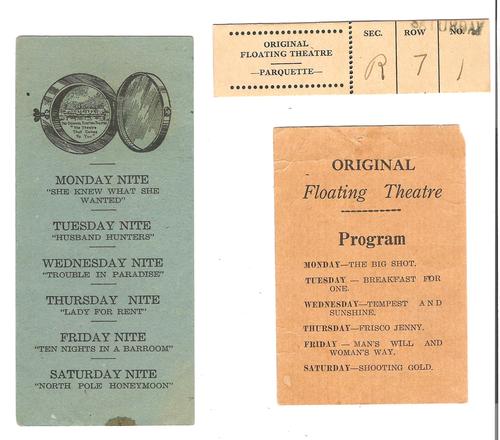

The James Adams Floating Theater’s bulk dockside was a Faberge egg of delights that promised a panacea for humdrum hamlet life: a week of nightly romance, adventure, comedy, and music in the 800-capacity auditorium. As long as they had a water access and a few dimes squirreled away, audiences along Bay tributaries could sigh with the lovelorn ingénue in Tempest and Sunshine, discover ‘whodunnit’ in The Boy Detective, and shout with encouragement as winsome cowboy defeated the magnificently-mustached villain in Sunset Trail. From 1914 to 1941, the James Adams Floating Theater enchanted small towns and cities throughout the Chesapeake’s tributaries. Long after its circuit was abandoned for newfangled talkies and colored pictures, the legacy of the magical little showboat lived on in the memories of its audiences.

The Floating Theater was the brainchild of a seasoned entertainer and vaudevillian, James Adams, who had made his fortune in the travelling carnival business. In the late 19th century, while a retinue of showboats plied their trade throughout the rivers of the Midwest, Adams discovered while working the carnival circuit in the Southeast that the East Coast was still wide open to the opportunity.

A write up on the Floating Theatre from the Baltimore Sun, November 22, 1925. Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

It was a time period when, according to the US census, over 60% of the American population still lived in rural, agricultural communities. But even the humblest of towns often boasted its own theater, an outpost of civilization and culture in remote locales. These small stages, ranging from utilitarian platforms to elaborately appointed entertainment palaces, hosted various troupes of travelling performers during the heyday of the “American Repetoire Theater Movement.” During a peak of popularity that lasted for the first four decades of the 20th century, travelling Repetoire companies, comprised of a corps of versatile actors and musicians, provided the main source of entertainment for small town America. Melodramas, musicals, and romantic comedies were the most popular offerings, followed by farces and minstrel shows. Modern audiences would find the fare low-brow and hammy, but in farm towns and fishing villages, it was an escape from the hard physicality of a world where machines had just begun to make everyday life easier.

James Adams, a savvy showman, knew well the demand for small-town travelling entertainment, and set about capitalizing on it in 1913 with the construction of a 128-barge in Washington, North Carolina, named Playhouse. Within its 30-by-80 foot auditorium appointed in a cream, blue and gold color scheme, there was room for 500 on the floor and 350 in the balcony, providing the capacity to perform to entire towns. Adams spared no expense- his “Floating Theater” boasted a stage, room for a 10-piece concert band and a 6-piece orchestra, a galley, a dining room, running water, and room for 25 live-aboard cast and crew. The exterior was painted an immaculate white, with dark trim, porches and balconies.

The Floating Theatre’s interior. Image courtesy floatingtheatre.org

Its design, however, was pragmatic as well as pretty- drawing only 14 inches of water when it was empty of audiences meant the Playhouse could easily reach the little towns crowded like barnacles alongside the Chesapeake’s shallow tributaries. Towed by two tugs, Trouper and Elk, on either end and emblazoned with “James Adams Floating Theatre” in lettering 2 feet tall, the theater’s buoyant bulk made its leisurely way to river communities throughout the watershed in the season between April and November.

Once the Floating Theatre appeared dockside, its small-town hosts could anticipate a week of nightly entertainment, from plays and musicales to concerts of the latest popular tunes. Vaudeville bits and specialties performed by actors and musicians in the company added variety and comedic relief to the playbill. While the company was in a state of constant change, with new members being added and subtracted every season, a few regulars cottoned to the nomadic lifestyle of the Playhouse and became featured stars of the theater’s reviews. Beulah Adams, the sister of James, performed trademark roles as the paragon of the blushing ingénue. Known as the “Mary Pickford of the Chesapeake,” with her trademark sausage curls, dimpled smile and petite stature (as well as the help of some artfully-applied stage makeup), she continued performing convincingly as a young girl on the Floating Theatre’s stage until she retired at the age of 46.

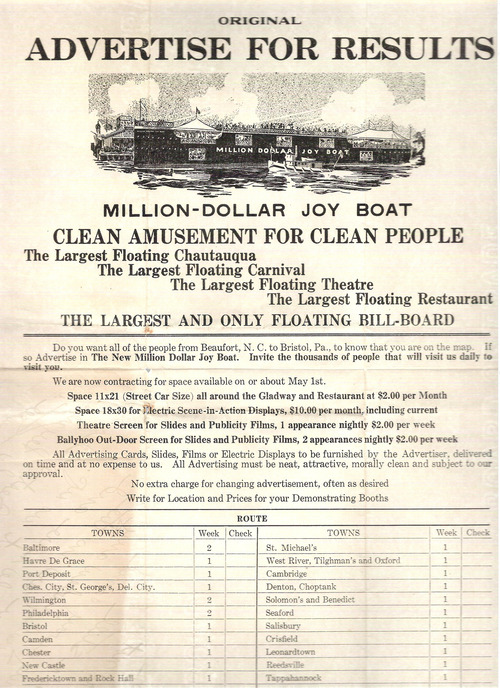

An solicitation for advertisers along the route of the Floating Theatre. Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Charles Hunter, Beulah’s husband, was another longtime Floating Theatre troupe member, playing character roles from straight men to love interests. During the vessel’s second season in 1915, he joined the cast, eventually moving up to direct plays and provide artistic oversight. Hunter, although a versatile and competent actor, was dogged by his extremely poor eyesight. To look younger for roles, he’d remove his thick glasses before going onstage, but had to cling to the curtain while entering and exiting and blindly grope his way back to the wings once his act was over.

Pop Neel was another longtime Floating Theatre cast member. A grizzled veteran of the carnival circuit, Neel had played with scores of circus bands until he came aboard the Playhouse in 1914 at the age of 56. A cornet player, Neel played competently until his age and health began to take their toll on his teeth. By the early 30’s, his dental state was as dilapidated as an old picket fence, and in order to have him continue to perform, the Floating Theatre’s management bought him a bass fiddle that he played until his retirement in 1939 at the age of 79.

Locals were encouraged to support the Showboat’s visits, which resulted in some special perks for those willing to pitch in. Young boys were often singled out for minor chores, toting and fetching, in exchange for tickets to that evening’s entertainment. Hartley Bayne, a Crumpton resident in the 1930’s, remembers the thrill of “working” for the Floating Theatre as a ten-year-old: “The actors had their private rooms on the Showboat. They had to have fresh water, water to bathe in. So the boys in Crumpton, and I guess, Centreville and Chestertown, we carried buckets of water up and I would do two different actors’ rooms at a time, so all of them had fresh water. And that night, I’d get in free, because I was a waterboy.”

Bayne later became a pen pal with one of the actors, Thayer Roberts, whom he’d befriended during a visit in 1935. Roberts, a seasoned vaudeville performer, went on after his stint with the Floating Theatre to transition from theater to film and played bit roles in B movies for the rest of his career. Though his life took him far from the sweltering tidewater where he’d trod the boards for small-town audiences, it seems he never quite managed to forget his summers aboard the Floating Theatre. From time to time for the next decade, he’d sit down in his home in the Hollywood hills to write to the scrappy water carrier from Crumpton who would grow up to be my grandfather.

Floating Theatre tickets and playbill. Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Not all audiences were equal, however, for the Floating Theatre. This was the heart of the Jim Crow era in the Chesapeake, when separate-but-equal was anything but, and the showboat was no exception. Anticipating mixed-race audiences, the balcony was originally advertised in 1914 as “reserved for colored people exclusively,” a novel arrangement for the time that galled many conservatives who preferred their entertainment be strictly segregated along racial lines.

Charles Hunter would go on to take his Floating Theatre bits on the road. This playbill from his "Showboat Players” and its inclusion of a minstrel show conveys the sharp disparity between what historical and modern audiences consider to be “entertainment.” Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

However, the attempt to draw more diverse audiences proved to be a failure for the showboat- regardless of their ‘forward-thinking’ separate seating. For African-Americans in the Bay region, many restricted to low-wage menial jobs, the ticket prices were far beyond affordable. James Adams acknowledged this disparity when interviewed for The Saturday Evening Post in 1925 commented to the interviewer, “The 20-35-50 cent scale is a bit beyond the range of the negro population. Most of them… (wait) on the wharf, listen to the music inside, and wait for the 15-cent concert after-show.”

A showboat staffer in the late 20’s and early 30’s, Maisie Comardo, identified another reason that African-Americans avoided the Floating Theatre- curfews. Commardo reflected in an interview years later that many African-Americans did not want to linger in the white part of town as late as the concert ended. Frequently, small Chesapeake towns restricted their main streets after hours for white-only use, with violent repercussions if those restrictions were ignored. For many locations throughout the circuit, that curfew would have started before the showboat’s final curtain call- effectively eliminating any chance of attendance for all people of color in the community.

First edition cover of Edna Ferber’s “Showboat.”

The Chesapeake’s racial disparities highlighted by the James Adams Floating Theatre were to become nationally famous when the Playhouse was immortalized in Edna Ferber’s novel, Showboat. Ferber had first visited the Floating Theatre in 1924, while the vessel was in Crumpton, Maryland for a week, and later travelled to North Carolina in the spring of 1925 for a second, longer stay. Through her own observations and interviews with cast on the Floating Theater, especially Charles Hunter, Ferber compiled extensive notes onboard the Playhouse, documenting the culture and community of the little showboat and the isolated tidewater towns it visited. Ferber later described the rich content of her interviews with Charles Hunter, who was a bit of a raconteur once he finally opened up: “Tales of river. Stories of show boat life. Characterizations. Romance. Adventures. River history. Stage superstition. I had a chunk of yellow copy paper in my hand. On this I scribbled without looking down, afraid to glance away for fear of breaking the spell.”

Ferber published Showboat to public acclaim in 1926- it spent 12 weeks on the New York Times Bestseller list, and inspired a blockbuster Broadway musical of the same name in 1927. Although the story was fictionalized with a Mississippi setting and an imaginary cast of characters, the glories of the Floating Theatre’s limelight and the cruelties of the Jim Crow Chesapeake were addressed with arresting realism on Ferber’s Cotton Blossom. Immortalized on the page, the stage, and in 1936, on the big screen, the success of Showboat helped to ensure that the memory (albeit slightly embellished) of the James Adams Floating Theatre might fade from public recollection, but it would never disappear entirely.

The publication of Ferber’s Showboat and the subsequent adaptations that followed marked the acme of the Floating Theatre’s history. As its star set, the movie industry and radio were becoming powerful cultural juggernauts, supplanting Repetoire companies as the small-town choice for entertainment. By the late 1920’s the Floating Theatre was facing hard times. In 1927, she sank near Norfolk Harbor, requiring expensive repairs, and again in 1929, near the Great Dismal Swamp. The Great Depression only continued the downward spiral for the showboat. Entertainment became a luxury for down-on-their-luck audiences who keenly felt the pinch in their pocketbooks.

By 1933, it was the end of an era. James Adams sold the Floating Theatre to a St Michaels woman, Nina B. Howard, who managed the boat with the help of her magnificently-monikered son, Milford Seymoure. Although Beulah Adams and Charles Hunter stayed under the new management, times had changed and business continued to fall off. Audiences throughout the showboat’s circuit were no longer transported by the sentimental romances and slap-stick comedy after experiencing the elaborate sets and subtle, emotional acting of the moving pictures. By 1936, Hunter and Adams finally quit and began a land-based touring company. In 1938, the showboat sank for the third time in the Roanoke River.

Three years later, again under new ownership, the Floating Theatre caught fire in Savannah, Georgia. Her flocked wallpaper, dressing rooms with knotty pine, cramped, oil-splattered galley, and the gold and silver painted seats of her auditorium flickered in the blaze of her final curtain call. It had been a good run. So many dusty Chesapeake towns had drowsed under the Floating Theatre’s spell, roaring with laughter, crying in sympathy, clapping their hands and singing along to “Buffalo Girl” and “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.” Through World War I, the Depression, the great monolithic hulk of the Floating Theatre approaching downriver meant diversion from your troubles, a blissful cocktail of comedy, razzle dazzle, and glittery fantasy.

Although audiences would never again gather each night by the town wharf, ticket in hand, her music and her mugging entertainers would live on in their delighted memories, and in the stories they told to their children and grandchildren. Certainly, my grandfather was no exception. “It was special to be picked, and I went to help every day, so I could go at night,” said my Pop-pop, Hartley Bayne, reminiscing about his water boy days in Crumpton. “It was the best week of the year, and everybody in the whole town was there, at the showboat.”

William “Wit” Garrett recalls taking a date to see a show at the Floating Theatre in his teens:

An effort is being made to recreate the James Adams Floating Theatre. Read more about the project here: http://floatingtheatre.org/