Vanishing Landscapes

The Chesapeake today is just a thin skin of soil and time on top of the barely-concealed remains of the past. Old osage orange hedgerows, overgrown and serpentine, mark the field boundaries of the 18th century. Arrowheads and prehistoric shark’s teeth wash up regularly on beaches after a spring rain. And at the end of thousands of dirt lanes, overgrown and disused, old houses disassemble themselves.

Haden Hall, Long Yard

Though they might have been built at great expense, and taken years to construct, their demise is usually unceremonious. They fall apart, leaded windows cracked and shattered, sunshine streaming through the roof. Without people to shelter, their souls depart. They are giant, weathered headstones in a mown field of cornstalks, a silent witness to the life there a hundred, two hundred years ago.

Slave quarters at Poplar Grove

These images, by photographer and CBMM lecturer Shirley Hampton Hunt, are a testimony to the potency of decay- which, in the Chesapeake area, is an incredibly commonplace phenomenon, especially for old houses. Depending on the material and the age, the building may be a matchstick pile or seem to have barely suffered the depredations of time, but these abandoned places haunt almost every neighborhood, farm lane, and field. Their “everyday” quality does not diminish our fascination with them, however, for they are as full of questions as they are empty of people. Who built them? Who lived here and when? What would it have been like to live in this old house, walk these old floors that were once smooth? Why was this house neglected and forgotten?

Wickersham, Talbot County

It’s easy to imagine a house like Wickersham (which, since this photo was taken, has been moved to St Michaels and restored) in her heyday, and in your mind, the glass is replaced in the window lights, the steps extend from the front door to the grass, maybe roses bloom nearby. It’s a house that calls for a family- expansive enough for the people that built it and the slaves they owned, too. Looking past the slitted boards on the windows, they still seem present, if just in the atmosphere emoted by the brick and mortar. In places like Wickersham, they are so easily resurrected because they are thoroughly worn and shaped to human use, and even a long spell of decrepitude seems like just a temporary pause in their centuries of habitation.

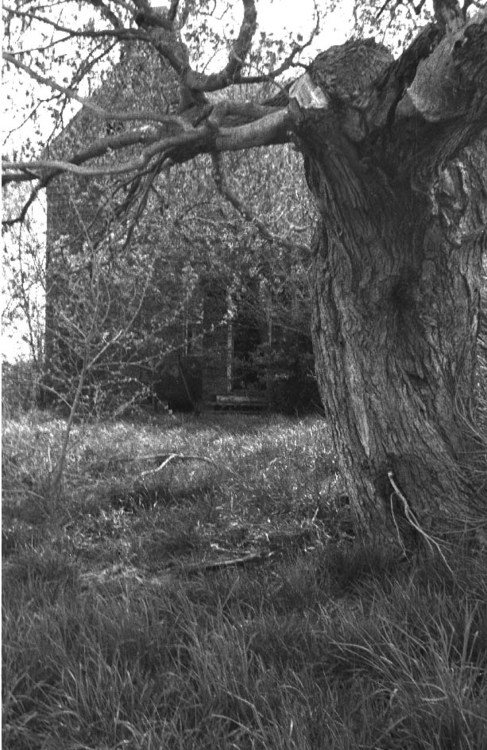

The Guardian

Even if these remote dwellings and outbuildings are one lightning strike away from a pile of cinders and smoke, they still have a resonance. They convey so much about the Chesapeake that was, and create an significant aesthetic element of the Chesapeake that is. It’s a place where land and water, past and future are deeply and irrevocably intermingled. And under each sagging porch where raccoons hide, in every mildewed barn loft, behind the glass where the dead bluebottles are drifted, a part of that sense of place is captured and remembered, if with each day a little diminished as the wood and brick return to soil again.

Barn, John Powell Road

All images courtesy of Shirley Hampton Hunt: http://bit.ly/YjcJvz