Oyster middens- the ghost of oysters past

Oyster midden overlooking the Chester River.Image by author.

Throughout the Chesapeake, where the mixture of salt and fresh water is just right, thin wafers are tumbled by the tide. Faded remnants of once robust oyster beds, these are middens- oyster shell beaches testament to the Chesapeake's past oyster populations. Made up of discarded oyster shells, middens still exist where often no oysters thrive today. Beach glass and pebbles are mixed into the softly crumbling oyster shells, and often beachcombers will find arrowheads or pottery and other detritus from the people that came down to the shore, ate oysters here, and left. Middens can be hundreds or even thousands of years old. Some are colonial, many are pre-colonization remnants of Indian winter camps. All are ghosts of a sort, haunting our contemporary landscape with reminders of the winter feasts savored, centuries ago.

A midden on Eastern Neck Island. Image by author.

A Virginia midden- mussels, oyster shells, and reeds. Image by author.

I love middens, but then again, I love to feel like I am cheek-to-jowl with the past. The experience of almost-tangible time travel is addictive. Middens powerfully convey that feeling, existing along Chesapeake tributaries too fresh, too sedimented, or too degraded to support the delicate balance of an oyster colony. HERE, they say, is what this Bay used to be like. You could fill your belly on an oyster bar where today there's a marina, a road, an empty stretch of cornfield, the terminus to an overgrown trail. Oyster middens convey a subsistence past where today only a convenience culture persists. Like old paint peeling off a wall, middens reveal history hidden just below the surface- faded, but persistent, and beautiful.

Weird oyster stuff- oyster trade cards

Louis Grebb trading card, 1888.

Oysters- wet, maybe a little mucosal- don't seem like exactly the most appetizing food to promote, right? Au contraire! Oyster packers and the lithographers working for them during Baltimore's golden era of oystering came up with endlessly creative solutions to solve the oyster's little 'image problem.' From humorous cartoons like the snooty oyster bar patron on Grebb's trade card above, to beautiful ladies, babies and puppies, pretty much any strategy was used to move Baltimore oysters.

Hitchcock oysters trading card, late 19th century.

These trade cards were used like a combination of a modern business card and a flyer. Used by tradesmen, they were handed out widely to restaurants, grocers, and oyster bars as a way to promote their brands. Usually, the reverse side would have particulars about the cost of oysters in bulk or the name and contact information of the brand representative.

Grebb Oyster trade card, 1888.

Oyster packers had more than one kind of oysters to sell- steamed (bulk), canned, or oysters in the shell. Often, processors switched to packing fruits or vegetables in the summer when oysters were out of season, so Louis Grebb is offering both.

Baltimore Cove Oysters, late 19th century

These oyster trade cards utilized the new printing technique of lithography, and evolved at the same time as their far more famous relative, baseball trade cards. Several lithography firms were working in Baltimore by this era, the most famous of which was A. Hoen and Company- a lithographer that printed maps, tobacco labels, sheet music, posters, and oyster trade cards during the end of the the 19th century. A. Hoen's lithographic style, and that of many of their competitors, was greatly influenced by the style of political or satirical cartoons popular in magazines during the late 19th century. However, that meant that often oyster trade cards included imagery considered humorous by the Victorians that today reads as inappropriate or just racist.

J. Ludington and Co Oyster trade card, late 19th century.

Like oyster cans, brightly printed, lively trade cards are highly collectible today. Fans value their whimsical graphics but also their glimpse into a part of the Chesapeake's bygone Oyster Boom, when a bushel of oysters cost $3, the Bay's seemingly endless oyster bounty supportedalmost 20% of the city's population, and the wonders of marketing were transforming oysters from quotidian part of the diet to Chesapeake brain food.

J.T. Stone and Company trade card, late 19th century

Chesapeake Oyster Packinghouses- The Brisk, Brutal Bay Shellfish Business

Harper's Weekly illustration of a Baltimore packinghouse, March, 1872. Collection of author.

Oystering in the 19th century was a nasty business. Shellfish harvests were highly competitive, prices were high, and little heed was paid to harvesting regulations (or the Oyster Navy enforcing them). People killed over access to oysters and the money they represented, and whether that meant a oysterman murdering an immigrant crewmember or a tonger gunning down a rival skipjack captain, anarchy prevailed. By the late 1800's, oyster poaching and general lawlessness was rampant on the Bay's byways- all to feed the ceaseless demand of the oyster packinghouses in Baltimore, Crisfield, Solomons, and Norfolk. In each city, hundreds of packinghouses competed for dock space and consumer adoration, turning out hundreds of thousands of cans from each brand every year. Transported by rail, these cans of Chesapeake oysters brought the brackish taste of the Bay to hungry Americans across the country, in communities thousands of miles away from the coast.

Oyster shuckers, Rock Point, Maryland. Image from the Library of Congress collections.

Oyster packinghouses, although far less likely to incite murder, were another often unsavory link in the processing chain that moved oyster from the Bay to markets across the country. As the image above shows, these were wet, dark, cold places where oysters were shucked, packed and shipped by an immigrant or African-American workforce. An industrial report in 1886 described the workers in one of Baltimore's 45 packinghouses: " The oyster shuckers are a vert hard working, good-tempered- if not very clean- community; their morals are not very strict, if their conversation is a criterion, and the standards of intelligence is certainly low." The reporter went on to state the average wage for one of these maligned workers- a paltry 5 cents per can.

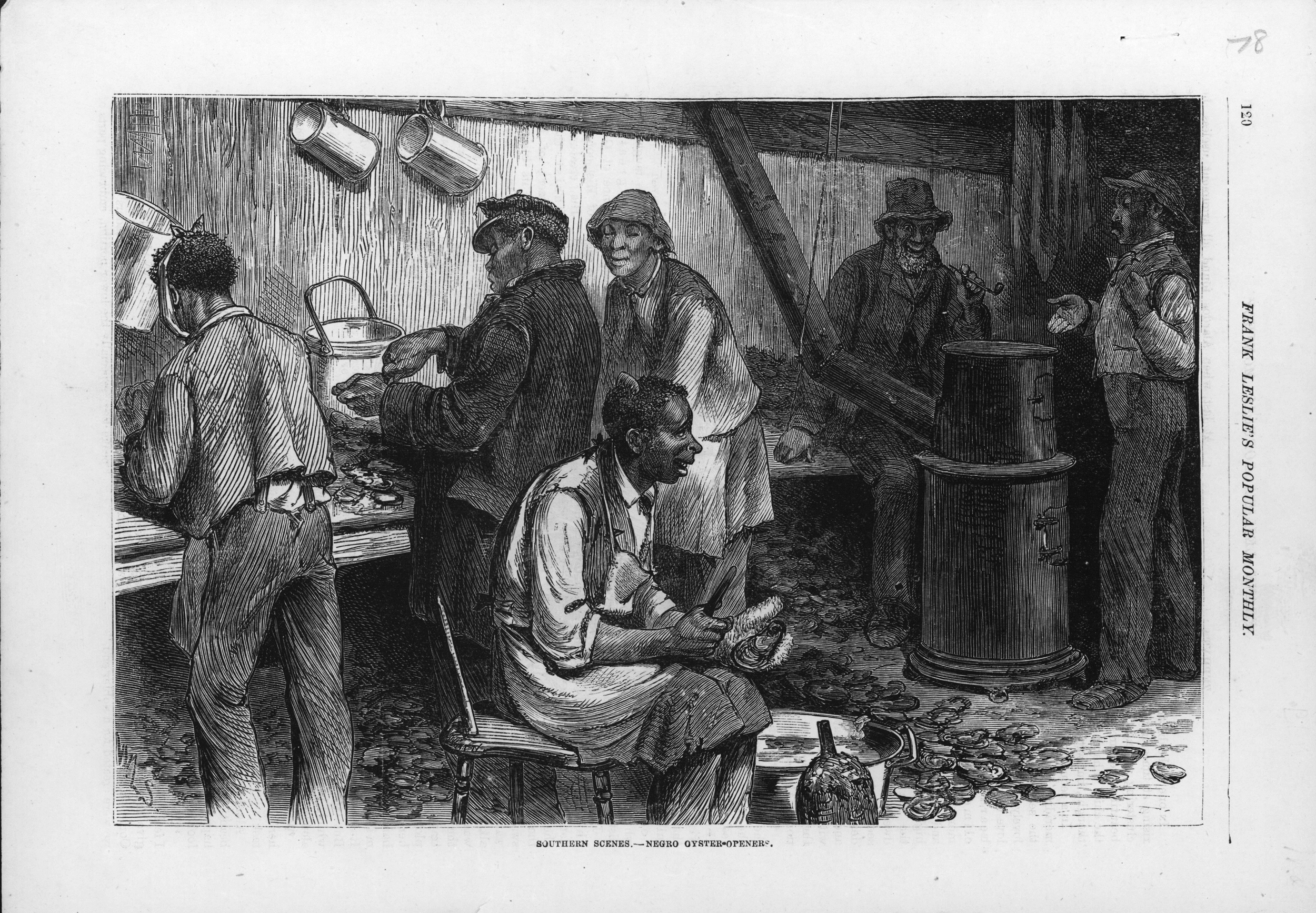

Image of a crisfield packinghouse, Frank Leslie's Weekly, 1878. Collection of Author.

Crisfield, Maryland's packinghouses were largely supplied by African-American labor, unlike Baltimore, where German and Irish immigrants made up the majority of the workforce. Many of these shuckers, washers, blowers, measurers, and fillers were once slaves who now toiled for nominal wages at the town's 16 different packinghouses. In 1880, one report estimated that out of 678 employees working for oyster packers in Crisfield, 500 of those were African-American. Together, these shuckers had packed 427,270 bushels of oysters in a single year.

"Little Lottie, a regular oyster shucker", by Lewis Hine, 1911. Library of Congress Collections.

Children frequently worked alongside their parents in the gritty, steamy packinghouses, shucking oysters while standing on drifts of slowly rotting shells. It was a frequent sight in the era prior to child labor laws, and a reminder that like New England's mills or West Virginia's coal mines, oyster packinghouses were one part of the vast Industrial Revolution that ground along on human cogs. Indeed, Thomas Kensett, one of the founders of Baltimore's oyster canning industry, proudly stated in 1869, "Were it not for the shucking of oysters, many children, from twelve to fifteen years of age, would spend much of their time in the streets and around the wharves and docks, being trained up to immorality and crime, and preparing to fill up our jails and warehouses."

A Baltimore worker individually solders the oyster cans before shipping. Harper's Weekly, 1872.

For 60 years, packinghouses were the lifeblood of the Chesapeake's waterfront communities. Even small towns might have one that packed tomatoes in summer, and oysters in winter, or later when the oyster harvest declined, transitioned to picking and packing crabmeat.

Today, all but a notable handful of these packinghouses are gone, and the few that are left often employ a combination of locals with an influx of immigrants from Central America on H2B visas. JM Clayton's in Cambridge, Metompkin in Crisfield, Chesapeake Landing in St Michaels- these businesses have managed to survive even as their traditional workforce has moved on to jobs with benefits, salaries and indoor heating, and as the Chesapeake oyster industry has plummeted and started to rise again. Despite these changes, much remains the same for the Bay's remaining oyster packinghouses. It is still dirty work, it is still a job where shuckers get paid by the pound, and one where English is still intermingled with many different languages- all down a long packing table where oysters are shucked by deft hands, faster than the eye can see.