French Oysters- PART I

Oysters on offer in Paris' Buci Market

While in America it's the season to be merry, in Paris, that merriment isn't found under a tree- it's found inside an oyster's shell. Here, deep winter means oysters- the traditional food of Christmas and New Year's Eve. In fact, almost 50% of the 130,000 tons of oysters annually produced in France are eaten over the holiday season, and all of those oysters are raw. Oyster vendors are all over the Paris streets, and every bistro seems to have scores of patrons sitting in outside in winter coats, savoring their briny, freshly-shucked shellfish with copious quantities of dry white wine.

Oysters, prawns, crabs and snails are all beautifully displayed to tempt hungry Parisian passerby.

Much of the American shellfish consumerism has echoes of the French tradition. Today, the Chesapeake is just beginning to differentiate between oysters from different regions and to brand each variety as unique. For the French, distinguishing the different properties of 'merroir' is old news. They are oyster lovers, going all the way back to the first oyster connoisseurs, the Romans, whose oyster culture and obsession were as much a part of the Empire's legacy as viticulture and wine. The Romans conquered the Gallic Celts and set about sampling their shellfish- and when possible, shipped them back to Rome for the luxury seafood market. As with the English oyster tradition that I explored in Chesapeake Oysters, the Romans helped the French recognize the rare treat they had abounding in their vast coastline.

The native oyster, Crassostrea edulis, is a rarity in France, where 90% of the oyster harvest is the asian Crassostrea gigas. Marketed as "plates" or "Belons," these round, flat oysters have an intense flavor profile with a strong coppery finish.

The oysters the Romans favored and that later became an essential part of the French diet in the 19th century are not the same species of oysters modern Parisians enjoy, by and large. The native Crassostrea edulis- wide, flat, round and with a taste like licking a copper penny- were decimated by mysterious diseases in the 1920's when oyster science was still in its infancy, and a different species, Crassostrea angulata or the 'Portuguese oyster,' was introduced to continue to support the market. The Portuguese oyster was widely popular (and is still invokes much oyster nostalgia today amongst those who remember its apparently unparalleled flavor) until the 1960's and 1970's, when two diseases, Marteilia refringens and Bonamia ostrae destroyed the oyster stocks. By the late 1970's, France's oyster production had declined from 20,000 tons to only 2,000 tons a year. In response, the French embraced a non-native species- Crassostrea gigas or the "creuse" oyster- as part of the state's "Resur" plan. The introduced oysters flourished where the angulata had perished, and today gigas oysters are now ubiquitous in the country's oyster regions- representing 90% of France's annual oyster production. Edulis varieties are still produced, though they are much more rare, and as you might guess, significantly more expensive than the common gigas varieties.

No 2 and No 3 oysters displayed in a street market.

All this history and context said, though, oysters are meant to be eaten- and to help guide consumers along the way, France has developed a framework for its oyster growers, differentiating by size and by intensity of cultivation. The sizing is simple- oyster range between a size 5 at the smallest and a size 0 at the largest. Unlike the States, where plenty of folks will fork over a premium for a Kumamoto the size of a squirrel's ear (many women in particular disdain large oysters- take that as you will), here bigger oysters cost more. It makes sense in terms of sheer volume, so those who prefer smaller oyster should take note- France will treat you right!

From top right: 6 fine de claires No.3, 6 speciales de claires No.3, 6 pousses en claires No.3, and 6 perle blanches No.3.

The other method of differentiation between oysters has to do with production quality. France has seven different oyster production zones that are treated much like wine appellations on land. Oysters from these regions, ranging from Normandy in the north to the Thau lagoon in the Mediterranean, all have specific flavor profiles reflecting the salinity, tidal activity, and algal concentration of the local environment. Also, depending on location, oysters might be raised in bags, on ropes, or through extensive culture (scattered on the bottom of the sea). However, just raising oysters to market maturation is not considered enough. Unlike in the United States, where a strong taste of the sea is preferred, the French like their oysters fat and sweet. To achieve this, oysters are finished in man-made salt-water ponds known as 'claires.' These ponds are infused with pulses of freshwater, and their high algal content allows oysters transferred from the ocean to fatten and to take on unique, complex flavor profiles. The longer oysters are finished in claires, the more their taste matures and the fleshier they become.

Edulis Oysters in a claire at Belon. Image from wikimedia commons.

Often, middlemen will buy oysters from regions like Normandy and Brittany known to produce meaty shellfish, and transfer them to claires for finishing, selling the final product at a higher profit. These claire oysters are differentiated by how much volume their meat takes up within the oyster shell. The longer they've been in a claire, the more algae they've eaten and the fatter they are. Salt water oysters, known as 'fines' are the least fat, and 'speciales' are the next weighty. 'Fine de claire' is reserved for claire-finished oysters of the next highest quality, while 'speciale de claires,' and 'pousses' move up the scale to 'perles' at the pinnacle.

Seafood stall on the Rue de Buci market.

All in all, it is a rigorous and intricate system developed over 120 years. Oysters here are strictly cultivated- ultimately a boon for the consumer. All this information is honestly quite more than most oyster eaters are interested in, so in my following post, I'll tackle the French oyster CliffNotes. What to choose? Which oysters are good? How are they served? What qualities define a 'good' French oyster? What is the French custom for eating them? What wine should I order to pair them with?

Check back later this week for your guide to ordering and enjoying oysters like a pro in France! In the meantime, as the French say, Bon Annee (Happy New Year) and more importantly, bon appetit!

Chesapeake Oyster Packinghouses- The Brisk, Brutal Bay Shellfish Business

Harper's Weekly illustration of a Baltimore packinghouse, March, 1872. Collection of author.

Oystering in the 19th century was a nasty business. Shellfish harvests were highly competitive, prices were high, and little heed was paid to harvesting regulations (or the Oyster Navy enforcing them). People killed over access to oysters and the money they represented, and whether that meant a oysterman murdering an immigrant crewmember or a tonger gunning down a rival skipjack captain, anarchy prevailed. By the late 1800's, oyster poaching and general lawlessness was rampant on the Bay's byways- all to feed the ceaseless demand of the oyster packinghouses in Baltimore, Crisfield, Solomons, and Norfolk. In each city, hundreds of packinghouses competed for dock space and consumer adoration, turning out hundreds of thousands of cans from each brand every year. Transported by rail, these cans of Chesapeake oysters brought the brackish taste of the Bay to hungry Americans across the country, in communities thousands of miles away from the coast.

Oyster shuckers, Rock Point, Maryland. Image from the Library of Congress collections.

Oyster packinghouses, although far less likely to incite murder, were another often unsavory link in the processing chain that moved oyster from the Bay to markets across the country. As the image above shows, these were wet, dark, cold places where oysters were shucked, packed and shipped by an immigrant or African-American workforce. An industrial report in 1886 described the workers in one of Baltimore's 45 packinghouses: " The oyster shuckers are a vert hard working, good-tempered- if not very clean- community; their morals are not very strict, if their conversation is a criterion, and the standards of intelligence is certainly low." The reporter went on to state the average wage for one of these maligned workers- a paltry 5 cents per can.

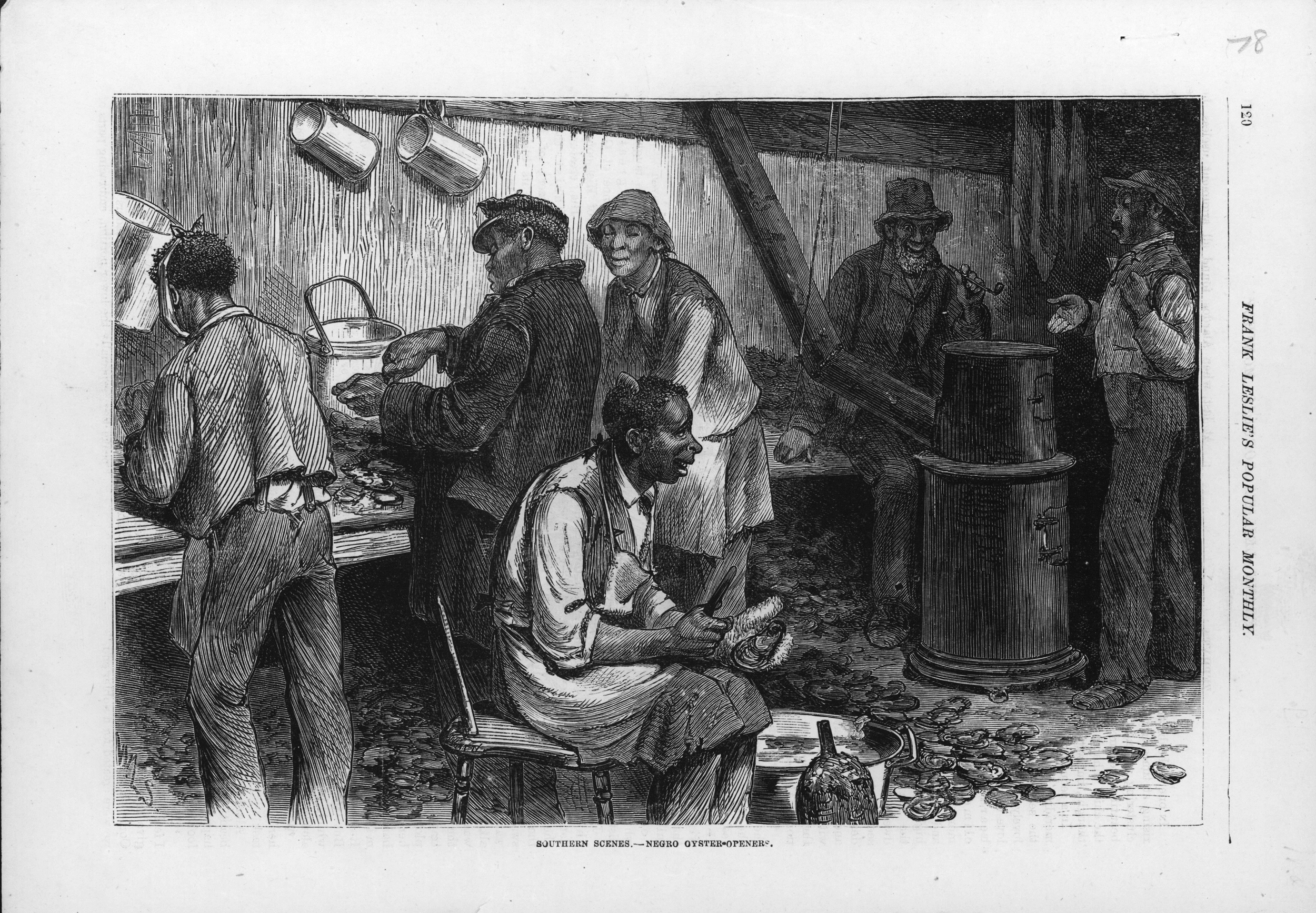

Image of a crisfield packinghouse, Frank Leslie's Weekly, 1878. Collection of Author.

Crisfield, Maryland's packinghouses were largely supplied by African-American labor, unlike Baltimore, where German and Irish immigrants made up the majority of the workforce. Many of these shuckers, washers, blowers, measurers, and fillers were once slaves who now toiled for nominal wages at the town's 16 different packinghouses. In 1880, one report estimated that out of 678 employees working for oyster packers in Crisfield, 500 of those were African-American. Together, these shuckers had packed 427,270 bushels of oysters in a single year.

"Little Lottie, a regular oyster shucker", by Lewis Hine, 1911. Library of Congress Collections.

Children frequently worked alongside their parents in the gritty, steamy packinghouses, shucking oysters while standing on drifts of slowly rotting shells. It was a frequent sight in the era prior to child labor laws, and a reminder that like New England's mills or West Virginia's coal mines, oyster packinghouses were one part of the vast Industrial Revolution that ground along on human cogs. Indeed, Thomas Kensett, one of the founders of Baltimore's oyster canning industry, proudly stated in 1869, "Were it not for the shucking of oysters, many children, from twelve to fifteen years of age, would spend much of their time in the streets and around the wharves and docks, being trained up to immorality and crime, and preparing to fill up our jails and warehouses."

A Baltimore worker individually solders the oyster cans before shipping. Harper's Weekly, 1872.

For 60 years, packinghouses were the lifeblood of the Chesapeake's waterfront communities. Even small towns might have one that packed tomatoes in summer, and oysters in winter, or later when the oyster harvest declined, transitioned to picking and packing crabmeat.

Today, all but a notable handful of these packinghouses are gone, and the few that are left often employ a combination of locals with an influx of immigrants from Central America on H2B visas. JM Clayton's in Cambridge, Metompkin in Crisfield, Chesapeake Landing in St Michaels- these businesses have managed to survive even as their traditional workforce has moved on to jobs with benefits, salaries and indoor heating, and as the Chesapeake oyster industry has plummeted and started to rise again. Despite these changes, much remains the same for the Bay's remaining oyster packinghouses. It is still dirty work, it is still a job where shuckers get paid by the pound, and one where English is still intermingled with many different languages- all down a long packing table where oysters are shucked by deft hands, faster than the eye can see.

Chesapeake Stabbers: Murdering Oysters Since 1880

Chesapeake stabber. Collection of Kate Livie.

Not all oyster knives are made the same. Although oysters are similar in shape and general appearance no matter where you go— only really varying in size and shell thickness— the knives for shucking them come in a whole array of shapes and sizes. That's because each region has developed its own way of prizing open an oyster. Here in the Chesapeake, we go in from the side. This technique, known as bill shucking, requires a knife that can coax open the narrow lip of an oyster's bill without breaking— and what's been created is known as the "Chesapeake stabber."

The knife above is a perfect traditional example. The bulbous handle provides a firm grip, while the delicate iron blade can nimbly pierce the thin seam between the oyster's two shells and detach the oyster's muscle without marring the meat.

It's a simple tool, really, but its beauty is in its supreme functionality. Developed in the 1880's, the style is timeless. Though fancier oyster knives exist (like this one or even this one- seriously??) sometimes, you just can't beat the classics.