Chesapeake Oyster Packinghouses- The Brisk, Brutal Bay Shellfish Business

Harper's Weekly illustration of a Baltimore packinghouse, March, 1872. Collection of author.

Oystering in the 19th century was a nasty business. Shellfish harvests were highly competitive, prices were high, and little heed was paid to harvesting regulations (or the Oyster Navy enforcing them). People killed over access to oysters and the money they represented, and whether that meant a oysterman murdering an immigrant crewmember or a tonger gunning down a rival skipjack captain, anarchy prevailed. By the late 1800's, oyster poaching and general lawlessness was rampant on the Bay's byways- all to feed the ceaseless demand of the oyster packinghouses in Baltimore, Crisfield, Solomons, and Norfolk. In each city, hundreds of packinghouses competed for dock space and consumer adoration, turning out hundreds of thousands of cans from each brand every year. Transported by rail, these cans of Chesapeake oysters brought the brackish taste of the Bay to hungry Americans across the country, in communities thousands of miles away from the coast.

Oyster shuckers, Rock Point, Maryland. Image from the Library of Congress collections.

Oyster packinghouses, although far less likely to incite murder, were another often unsavory link in the processing chain that moved oyster from the Bay to markets across the country. As the image above shows, these were wet, dark, cold places where oysters were shucked, packed and shipped by an immigrant or African-American workforce. An industrial report in 1886 described the workers in one of Baltimore's 45 packinghouses: " The oyster shuckers are a vert hard working, good-tempered- if not very clean- community; their morals are not very strict, if their conversation is a criterion, and the standards of intelligence is certainly low." The reporter went on to state the average wage for one of these maligned workers- a paltry 5 cents per can.

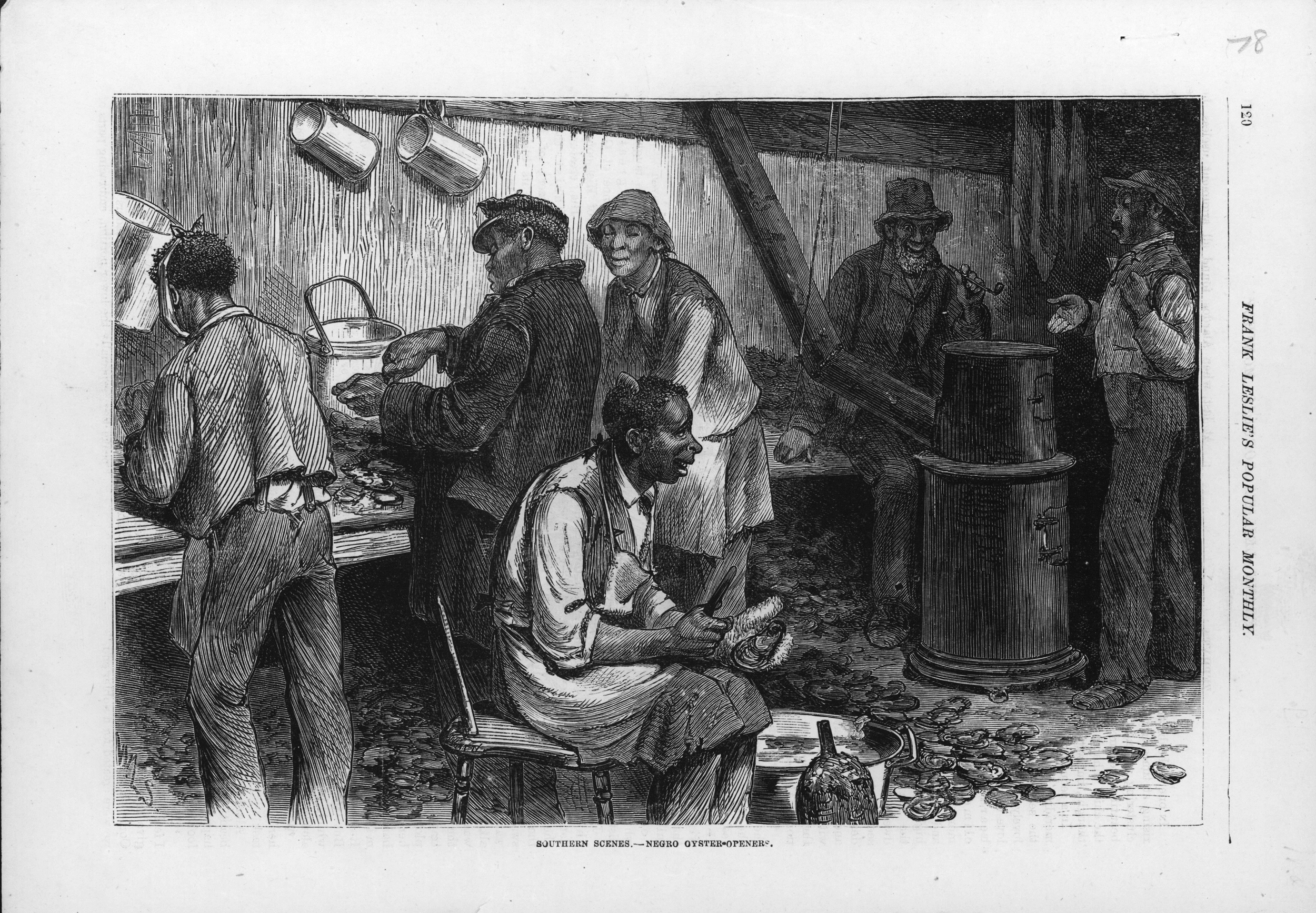

Image of a crisfield packinghouse, Frank Leslie's Weekly, 1878. Collection of Author.

Crisfield, Maryland's packinghouses were largely supplied by African-American labor, unlike Baltimore, where German and Irish immigrants made up the majority of the workforce. Many of these shuckers, washers, blowers, measurers, and fillers were once slaves who now toiled for nominal wages at the town's 16 different packinghouses. In 1880, one report estimated that out of 678 employees working for oyster packers in Crisfield, 500 of those were African-American. Together, these shuckers had packed 427,270 bushels of oysters in a single year.

"Little Lottie, a regular oyster shucker", by Lewis Hine, 1911. Library of Congress Collections.

Children frequently worked alongside their parents in the gritty, steamy packinghouses, shucking oysters while standing on drifts of slowly rotting shells. It was a frequent sight in the era prior to child labor laws, and a reminder that like New England's mills or West Virginia's coal mines, oyster packinghouses were one part of the vast Industrial Revolution that ground along on human cogs. Indeed, Thomas Kensett, one of the founders of Baltimore's oyster canning industry, proudly stated in 1869, "Were it not for the shucking of oysters, many children, from twelve to fifteen years of age, would spend much of their time in the streets and around the wharves and docks, being trained up to immorality and crime, and preparing to fill up our jails and warehouses."

A Baltimore worker individually solders the oyster cans before shipping. Harper's Weekly, 1872.

For 60 years, packinghouses were the lifeblood of the Chesapeake's waterfront communities. Even small towns might have one that packed tomatoes in summer, and oysters in winter, or later when the oyster harvest declined, transitioned to picking and packing crabmeat.

Today, all but a notable handful of these packinghouses are gone, and the few that are left often employ a combination of locals with an influx of immigrants from Central America on H2B visas. JM Clayton's in Cambridge, Metompkin in Crisfield, Chesapeake Landing in St Michaels- these businesses have managed to survive even as their traditional workforce has moved on to jobs with benefits, salaries and indoor heating, and as the Chesapeake oyster industry has plummeted and started to rise again. Despite these changes, much remains the same for the Bay's remaining oyster packinghouses. It is still dirty work, it is still a job where shuckers get paid by the pound, and one where English is still intermingled with many different languages- all down a long packing table where oysters are shucked by deft hands, faster than the eye can see.

10 Things You Didn't Know About Chesapeake Oysters

Chesapeake oysters- you pretty much know all about them, right? As in, they taste amazing with a dash of hot sauce and a cold IPA to wash them down, and you know how to signal the waiter for another dozen.

This is indeed pretty essential knowledge. Oysters are first and foremost a source of briny bliss. But they are so much more than that! Oysters are a connection with the Bay's environment, its culture, and its long traditions. They are a food, sure, but they also have sparked conflicts, supported an enormous economy, and changed the Bay's ecosystem in incredible ways- all things that even oyster connoisseurs might not be aware of.

So read on to see how savvy an oyster lover you are- and even experts might get a few morsels of information to share around the shucking table this Thanksgiving.

Crassostrea virginica oyster beds near Tom’s Cove, Virginia. Photo by Kate Livie

1. They are the same species as oysters from New York, Maine, Florida and Louisiana.

That’s right! Crassostrea virginica, the eastern Oyster is not only native to the Chesapeake Bay but way beyond- all the way up to Nova Scotia and down to the Gulf of Mexico. They have regional flavor distinctions, but every native oyster on the Eastern Seaboard is exactly the same biologically.

Illustration from The Oyster by biologist W.K. Brooks, 1905. Collection of Kate Livie

2. There are male oysters and female oysters, but they can swap genders.

To increase their chances of successfully spawning, oysters have a unique adaptation— they can change sex at will. Described by oyster biologist Trevor Kincaid as, “Strictly a case of Dr. Jekyll and Mrs. Hyde,” this versatility means the oyster population always a balance of enough males and females to ensure a healthy spat set. Most oysters start their lives out as males but become females by their second year.

Spat ‘seed’ at an aquaculture venture in Hooper’s Island, Maryland. Photo by Kate Livie

3. Baby oysters are called ‘spat.’

While it sounds like the past tense of ‘to spit,’ ‘spat’ refers to a juvenile oyster that has grown out of its free-floating larval state, when it is known as a ‘veliger.’ Once veligers develop a small ‘foot’ and attach to a hard surface (normally the shell of another oyster), they are then known as spat, and won’t move again for the rest of their lives.

Tiny pearls produced by Chesapeake oysters. Photo by Kate Livie

4. Chesapeake oysters produce pearls.

Almost all oyster species do. But typically, pearls— which are the product of an oyster coating an irritant with layers of nacre— look like the environment surrounding the pearl-producing oyster. In the brackish and algae-rich waters of the Chesapeake Bay, usually that means pearls that are brownish, greenish or just plain ugly.

Harper’s Weekly illustration from 1886 of a gun battle on the Chester River during the Oyster Wars. Collection of Kate Livie

5. People killed each other in order to get access to Chesapeake oysters.

In the late 1800’s, technology and transportation combined with an increase in demand lead to the great Chesapeake Oyster Boom. This period, which only lasted 20 years, inspired thousands of men to take to the water to harvest Bay oysters. These newcomers were usually on large sailboats known as skipjacks that used large tools to harvest millions of oysters. So much money was a stake that lawlessness prevailed— skipjack captains and crew got in gun battles with the regulating state Oyster Navy, took shots at oyster harvesters using old-fashioned attached rakes (called ‘tongs’), and the oyster tongers armed themselves and fought back. It was almost total anarchy that only ended when the oyster population started to decline at the turn of the century.

Chesapeake oyster on the half shell. Image by Kate Livie

6. Raw oysters are often alive when you eat them.

If they’re fresh, they might still even have a heartbeat. Raw oysters are living organisms, and when kept cold, they can survive for several days out of the water. If the idea of eating something alive bothers you, just steam them instead. Once the shells pop open, you know they’re ready to eat.

Natural Chesapeake oyster reef on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Image by Kate Livie

7. Chesapeake oysters grow in reefs.

Unlike cartoons, oysters don’t really lie on their side in the sand. They grow attached to each other, one generation after another, ideally close to the top of the water. In this way over thousands of years, oysters made reefs miles wide and miles long. Before mass harvesting methods, oyster reefs were so enormous, they were actual impediments to navigation in the Chesapeake Bay. A Swiss visitor to the Chesapeake, Francis Louis Michel, remarked in 1702 that, “The abundance of oysters in incredible. There are whole banks of them so that ships must avoid them. A sloop, which was to land us at Kingscreek, struck an oyster bed, where we had to wait two hours for the tide.”

A shucked Chesapeake oyster. Image by Kate Livie.

8. Oysters have clear blood.

The liquid inside an oyster, known as the oyster’s ‘liquor,’ is savored by oyster aficionados, who relish its briny taste. However, this is often a mixture of water and, when shucked, an oyster’s blood, which is totally clear. So if knowing they were alive didn’t kill your appetite, this might.

Farmed ‘triploid’ oysters at Ballard Oyster Company. Image by Kate Livie

9. Chesapeake farmed oysters are most likely sterile.

Known as ‘triploids,’ these sterile oysters have three chromosomes instead of the two found in normally-reproducing oysters. Triploids are used in Bay oyster farms— especially in Virginia— because they are more disease-resistant. Two oyster parasites that are harmless to humans but deadly to oysters, MSX and Dermo, have ravaged wild oyster populations in the Chesapeake. Unlike reproducing or ‘diploid’ oysters, triploids never experience the vulnerable weak period after spawning. Instead, they grow faster and make it to market before impacted by disease. For this reason, many oyster farms now use solely triploid oysters— better living through science!

The wide selection of oysters at a modern raw bar is a feast for the eyes as well as the belly. Image by Kate Livie

10. There is not just one kind of Chesapeake oysters.

Thanks to the growth of aquaculture, Chesapeake Bay oysters are now being produced by hundreds of oyster farms, each with its own brand of oysters. From Shooting Points to Pleasure House, each brand can offer up a slightly different tasting experience. Known as an oyster’s ‘merroir’ (like wine’s ‘terroir’) this distillation of an oyster’s environment can vary greatly depending on the location of the oyster farm— an oyster grown in a saltier part of the Bay might be very briny, while an oyster from north on the Bay might be much sweeter. Oysters that develop near marshes might take on an earthy note, while oysters grown near a cliff or rocky shoreline might have a more mineral finish. Try them all and find your favorite!

5 Ways to Savor Oysters Like a Pro

Sloppily-shucked oysters, torn meat, grit mixed in, oysters completely swamped with condiments— be honest— as an oyster lover, have you committed any of these oyster offenses?

In today's world where so many of excellent varieties of oysters are available, why are we settling for less when it comes to how they're served? To savor oysters like a real "ostreaphile," try a few of these tips the next time you order up a dozen at your favorite raw bar.

A variety of US oysters at a modern raw bar offers up plenty of flavor options to explore. Image by Kate Livie.

1. When more than one kind of raw oyster is available, order up a mixed dozen.

An oyster’s flavor can vary greatly depending on the environment where it was grown. Even oysters of the same species can have a remarkable range of flavors, and the best way to explore the incredible array of oysters is to compare and contrast. When you can, order a mixed dozen from two or more places (good raw bars will always tell you where their oysters are sourced), then sit back and enjoy- you’ll be amazed at the differences between the oysters.

An array of 'naked' oysters at Eventide in Portland, Maine. Image by Kate Livie.

2. Naked oysters first, condiments second.

Raw oysters have very delicate and complex flavors that are easily masked by condiments. Before you drown your oyster in hot sauce or mignonette, taste one plain. Enjoy the unique combination of brine, minerals, and notes of cream or cucumber that oysters can convey. After that, feel free to go crazy with whatever sauces or flavorings you like.

Freshly-shucked oysters at the 2013 Oyster Riot.

3. Never order oysters at a restaurant when you can’t see them being shucked.

Some restaurants still pre-shuck their oysters and let them sit. Not only does this dry out the oysters, but it can lead to food poisoning. Only order at a raw bar where the oysters are clearly cold, and if you want to know the particulars about their freshness, ask for the oyster’s tag. All restaurants are required to keep these on hand.

Salty Chincoteagues pair well with a hoppy beer. Image by Kate Livie.

4. To double your pleasure, pair your oysters with a complimenting wine or beer.

The right beer or wine can perfectly accent the flavors in your oysters- whether a dry white wine like a Sancerre or a hop-forward beer with very salty oysters, or a stout or Gewurtztraminer with a sweeter, buttery oyster from a lower salinity region. Try different combinations until you hit your favorite oyster and drink pairing.

Oyster spat attached to recycled bits of shell. Image by Kate Livie.

5. Oyster shells are not trash.

Oyster shells are an incredibly valuable resource for oyster reef restoration. Baby oysters, or ‘spat,’ need old shells to attach to in order to grow. Oyster shells have been depleted in many states, and the recycling of spent shell is a way to help aid oyster restoration efforts. So, don’t throw oyster shells away— and definitely don’t use them in your driveway or front path. Recycle them! Oyster shell recycling organizations are found throughout the Chesapeake Bay, and many restaurants have partnered with these organizations to make sure their shell is recycled. Always ask whether the restaurant recycles shell when eating oysters at a raw bar, and when at home, drop off your oyster shells at a recycling location. Save the Bay, one oyster at a time.