"Growing" Aquaculture at Ballard Oyster and Clam

A salt marsh in Chincoteague, with oysters breaking the water’s surface.

All the way down the long stem of the Eastern Shore of Virginia’s peninsula, a thriving industry exists in the salty marsh inlets and tidal coves. Where the water line breaks, they emerge: oysters. Thick and toothy, their grey backs crest above the surface as the water recedes with the tide. Exposed, these oyster reefs of peerless productivity show their complex structures, and all the hangers-on that survive inside: barnacles, mussels, shrimp, sea squirts, mud crabs, anemones. Oyster catchers, with their bright red bills and rabbit-red eyes, wade through the rubble spearing the finger-nail shells of spat. It all seems utterly untouched, wild, and timeless. But looks can be deceiving. These oysters, so expansively productive, are also intensely cultivated. Down here in Virginia, oyster leasing has been a part of the seafood industry for the last hundred years. After a century of farming, it’s clear even to the casual kayaker- this method has produced oysters so fertile every reed of marsh grass, piling, and submerged stick is covered in clusters of their spat.

Shellfish, especially the farmed variety, is big business down here- according to a recent article in the Washington Post, over two-thirds of Virginia’s current harvest of 405,000 bushels came from aquaculture. Currently, about 100,000 acres of the state water bottom is farmed by aquaculture leases. Clams as well as oysters are produced and shipped throughout the United States, where the terms “Chincoteague” and “Cherrystone” are synonymous with the best salty delicacies the Chesapeake can provide. Especially in the last ten years, this traditional bottom-leasing has been booming, with large-scale farms providing a substantial support to the growth of the oyster economy. On the deeply rural Eastern Shore of Virginia, this expanding aquaculture market may be the only kind of rapid growth many folks can support, if their bumper stickers are anything to go by.

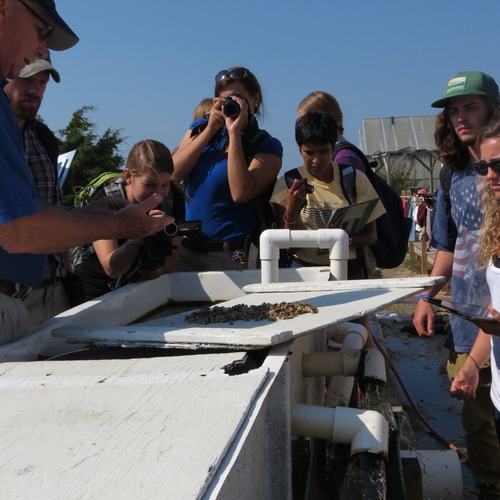

Our guide, Ron Crumb, a longtime Ballard employee, showing off Ballard’s harvest. Photo courtesy of Ballard Oyster and Fish company.

One of the best examples of the humble farmed oyster’s economic power is the Ballard Oyster and Fish Company, largest Eastern Shore producer of aquaculture oysters and clams. The company’s origins can be traced back to 1895, when a member of the Ballard family began working as a waterman. Throughout the early 20th century, the business was primarily run as a wild oystering concern, and the company grew as hundreds of additional leases were purchased. When MSX and Dermo began to impact the oyster population in the 1960’s and 70’s, the owner, Chad Ballard, turned the company’s energies to the stable hard-shell clam market, only reentering the oyster market in the mid-90’s.Today, they have two divisions- oysters and clams, each with several different lines to meet every market demand, and their employee roster includes as many as 120 people in the summertime.

On a recent tour of the Ballard main site in Cheriton, Virginia, we were met by the gregarious Ron Crumb, a longtime Ballard employee and the son of a waterman. He showed us the process of growing clams and oysters, both of which are produced in their on-site nurseries and then grown at multiple Ballard-leased locations offshore once they’re large enough. The tiny hard-shell clams were about the size of peppercorns, and there were millions of them in the outdoor tanks that continuously flushed with seawater.

Along the docks, the oystering side of the business was obvious- a towering pile of oyster cages, scarred with dessicated algae; bins full of spat ready to be moved into flats; a huge quick-sort machine on a barge laden with oysters. Bits of broken shell and crusted mud crunched under our feet. The smell of spent shell and the brine of decay was ripe in the day’s heat. Millions of oysters were transferred to and from the water here, and the evidence was clear to all of your senses.

Bags of baby clams being picked up by a worker in Ballard’s co-op.

Much of Ballard’s clam stock comes from co-operatives, where local watermen will buy the baby clams from Ballard, grow them on their own leases, and then sell back the surviving mature clams at a profit. It’s a method of aquaculture that has meant survival for many watermen in an era when its getting more and more difficult to make it as one-person enterprise, and there are dozens of members in the co-operative taking advantage of the arrangement.

Central to the facility is an immense packing house, where clams are separated by size and bagged, and oysters are packed and readied for wholesale. The first thing you notice is the temperature- it’s right around 40 degrees- perfect for keeping shellfish fresh, but a serious contrast to the 90 degree day outside. In these chilly conditions, dozens of workers guide clams into the sorter, bag them according to size and weight, and in the back, culling hammers help separate individual float-grown oysters from their clusters. There are also several packing houses offsite in Willis Wharf and Chincoteague, where Ballard’s bottom-grown oysters go for shucking and canning. It’s a massive enterprise that takes parts of the oyster and clam industry that were formerly separate and streamlines the process into multiple stages of a single system- Henry Ford would be proud.

The final products– cherrystones as sizeable as paperweights, and oysters whose edges curl like hair ribbons– are shipped via truck and plane to customers throughout the United States, where they impart the flavor of the Chesapeake environment to savvy shellfish connoisseurs. Ballard’s model has proven so successful that they’ve branched into multiple lines of oysters, each differentiated by size, taste, and origin. It would be no exaggeration to state that a consumer could eat a Ballard oyster every night of the week and not enjoy the same variety twice.

Some of Ballard’s different oyster varieties.

While aquaculture may not be the only way to successfully make it in today’s oyster industry, it is a method growing wildly in popularity in Virginia, where the concept of a bottom-raised oyster is a century-old news. Maryland has taken the first real steps to welcome aquaculture into its primarily wild-caught oyster industry, but in the last two years alone, multiple small companies have been founded by individual growers. It marks a change in tradition, technique, and culture, and there is no doubt that the inclusion of farmed shellfish in a primarily wild Chesapeake market will involve anxiety and an undertone of panic. But if Ballard is any indication, there is room for companies of this approach and scale in the Bay without the exclusion of the waterman’s trade- and if the co-operative example shows, perhaps to its benefit.

A future with more oysters in the Bay, a stronger oyster economy, and more fat, half-shelled beauties to enjoy is exemplified by Ballard Oyster and Clam’s present approach, a model for successful Chesapeake aquaculture.