Holland Island, Against the Tide

Once upon a time, there was a small marshy island in the Chesapeake. A fragment in a spinal strand of islands stretching from Bloodsworth to Tangier, Holland Island had a thriving community whose vitality reflected the richness of the Bay’s cornucopia. Finfish and crabs, oysters and turtles were harvested in their seasons by the residents of Holland Island, who numbered 360 souls by the beginning of the 20th century. Over the years, they established community hubs around which the wheels of island life turned: a church fringed by bay grasses, a two-room school, stores, a post office. Island afternoons in summer were peppered with the crack of baseball against bat at the island’s own white-limed diamond.

19th century image of Holland Island houses, located on the island’s highest ridge.

Holland Island’s church, school, and hall from a late 19th century photograph.

Holland Island’s mainstay was referred to as the “water business”, and a prodigious fleet of flat-white-painted workboats connected the islanders to the ballooning seafood industry in Baltimore, Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia. These were the island’s years of milk and honey. The tidily-prosperous Victorian houses that marched down the island’s backbone were a testament to the Chesapeake’s vast productivity in what would be later recognized as the “Golden Era” of Bay harvests.

Holland’s Island watermen checking their pound nets in the 19th century.

But Holland Island’s boom years were soon to turn with the tide, quite literally. Because every wave that kissed the islands shoreline also washed it away, at first imperceptibly, but with increasing speed and impact as the years went on. The slender ribbon of land that comprised the island, 1.5 miles in all, began to break up into smaller pieces as the Chesapeake encroached. The little community was now menaced by the same natural forces that had ensured its early prosperity.

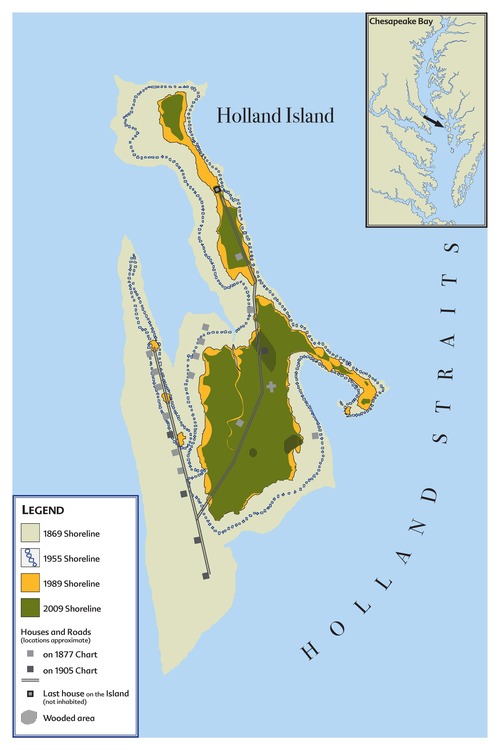

The map above shows the erosion of Holland Island over the course of 140 years. Once it was made up of 3 peninsulas which would become fragmented as the waterline reached further onto the land. Houses once located hundred of yards from the Bay became waterfront properties over the course of 100 years. A tropical storm in 1918 that severely damaged the church was the killing blow for the morale of Holland Island’s families. With few other options, the island’s residents began to relocate, dismantling their fine homes and rebuilding them in Crisfield, a town 8 miles away on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. They left behind foundations, bottles, buttons, and other miscellaneous detritus of everyday life. They also left behind their dead.

Photo courtesy of David Harp, http://www.chesapeakephotos.com

Aerial photo of Holland Island, 2011. Photo courtesy of David Harp, http://www.chesapeakephotos.com

For years, only one house remained on the island, which was eventually purchased by a former watermen and minister, Stephen White, who had visited Holland Island as a child. In interviews, he proclaimed his plans to rebuild the island, stating, “It’s a matter of will and ability. I have those, but I don’t have the funds.” For years, he lead a one-man crusade to stop the erosion of the now-depopulated island, traveling from Crisfield by motorboat each day to continue his efforts and forming a nonprofit tasked with saving Holland Island. He applied fruitlessly for state grants to reinforce the island’s shorelines, but the island was privately owned. So, with sandbags, rocks, and an old backhoe he toiled, one man against the tide.

Photo courtesy of David Harp, http://www.chesapeakephotos.com

For years, only one house remained, its toehold on the island’s extreme perimeter perilously shrinking with each rainy season. Well known to sailors, the Holland Island house became a visual touchstone for travelers passing through the island chain to the main stem of the Bay. Seabirds of all description were often lined up on the roof peak, a clamorous audience to the island’s final act. In mid-October 2010, the old Victorian house, peeling and hogged as a scuttled skipjack, finally crumbled into the Chesapeake that had so long labored to claim it.

Today, birds rule the island’s marshy acreage, safe in the knowledge that not a single predator lurks in the spartina. Each tide brings ghosts back of the families and community that once existed here: salt-stained porch trim in a whimsical pattern, a frosted green bottle for digestive tonic, the outlines of the last foundations and headstones, parting the verdant grasses before they, too, are finally submerged.