A workboat all ready for power dredging at a working waterfront on Deal Island, Maryland. Image by author.

Iconic Skipjack Dredging Licenses

City of Crisfield dredge license #33. Photograph by author.

There is much that is iconic about Chesapeake skipjacks- their long, wide-bellied form, their single masts and double sails, the weathered men who sail them to unseen oyster bars deep below the Bay’s surface. They have come to represent so much about the halcyon days of the Chesapeake’s past, when the water was the source of life and livelihood, and harbor towns hummed on the seasonal harvests: fish, crabs, and oysters.

But skipjacks have a whole visual language of tools and traditions associated with them, as well. As much as their towering cargo of shellfish, skipjacks are defined by the rusted dredges, white galoshes, and trailboards that encrust them like barnacles. Dredge licenses, those large, metal plates seen below the starboard and port lights on the skipjack’s rigging, are a part of that immediately-recognizable motley assortment of working objects.

Image of Martha Lewis, CBMM archives

These 24" x 24" metal licenses are now assigned to skipjacks for their entire life. But that is a recent development. Prior to 1971, captains had to reapply every year for a new set of dredging license plates. And the issuing of metal licenses was started in 1958. Earlier licenses were paper, and skipjack captains had to sew their license number onto their sails. It’s helpful tool for dating photographs here at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum- any skipjack photos that include sewn-on license numbers have to be earlier than 1958.

Oyster sloop J.T. Leonard displaying a pre-1958 dredge license. CBMM archives.

Modern metal dredge licenses are rare- just as rare as the few skipjacks that still sail on the Chesapeake Bay. Their maintenance is part of the annual spiffing-up that captains undertake to prepare their vessels for the working months. Decks and hulls are freshly painted with a new coat of white that hides the rust stains and oyster grit of last season, and their licenses are often given a brush-up too. Layers of paint on the licenses, thick as cake frosting, are a symbol of pride in continuing this diminishing way of life.

Dredging license, Rebecca T Ruark. CBMM archives.

Dredge licenses are not obviously beautiful adornments to the skipjacks they permit, but on closer thought, perhaps they are just right. Skipjacks are working girls, hardy, rough, and made for hauling, dredging, and sailing into headwinds. Flashy varnish or brilliant burgees wouldn’t suit these ladies. Their big frames are better set off by simpler things. Proudly painted and bright against a blue sky, dredge licenses are a skipjack’s crowning jewel, representing a working Chesapeake past that still defines our modern Bay.

Fannie Daugherty relaunch after restoration work at CBMM. CBMM archives.

The “Why Worry” out of Wenona, Maryland is having a good oystering season this year. Other watermen out of Deal Island on Maryland’s Eastern Shore have been meeting their limit, bringing in 100 bushels of oysters a day. It’s good news for watermen and the working fleet of deadrises on Deal, where oysters still represent a substantial part of the Bay’s winter economy.

Seen on the bridge to Assateague Island, where so many locals try their luck chicken-necking off the bridge for crabs that there are permanent crab-measuring stations at intervals. Only in the Chesapeake!

A fall fog stretches the horizon to infinity beyond our St. Michaels, Maryland docks at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

An Island, Recreated

Poplar and Jefferson Island, looking south. Photo ca. 1935 by H. Robins Hollyday, courtesy of Talbot County Historical Society.

Polar Island ca. 2008. Photo by Hunter H. Harris.

Over the centuries, many of the Bay’s islands have completely disappeared, washed away by wind and tide. During the period between these two photographs, Poplar Island nearly became one of them.

In the 1930’s, you can see the lee shore of the island scattered with the last of the island’s trees, which fell as the sand and soil washed out from under them. During that period, some prominent Democrats bought Jefferson and Poplar Islands and established the Jefferson Islands Club as a place for men honoring Jeffersonian ideals, “where the humdrum of party politics might be broken now and then by communion with the great outdoors.” Between then and 1946 when the clubhouse on Jefferson Island burned down, the islands were host to Franklin D. Roosevelet, Harry S. Truman, and innumerable Democratic congressmen, businessmen, and military generals.

Rep. Sam Rayburn, House Majority Leader, Secretary of War Woodring, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, Speaker of the House Bankhead, and Secretary of Agriculture Wallace leaving Annapolis for the Jefferson Island Democratic Club on June 25, 1937. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress collections.

Even as the clubhouse hummed with international leaders, the island was washing away. During storms, whole acres were lost to the relentless waves. Like many islands throughout the Chesapeake, it seemed fated to wash completely away, until Poplar Island became the focus of a stunning public works project. The US Army Corps of Engineers needed a place to put the millions of yards of clean fill dredged up from the shipping channel approaching Baltimore Harbor and carrying it across the Bay by barge to reconstruct the island. Poplar Island became the repository, and so was saved from inundation.

Double-crested cormorant colony on Poplar Island. Photo courtesy of the Chesapeake Bay Program.

By 2016, everything behind the retaining dikes built to define the island will be filled in, but that doesn’t mean that Poplar Island isn’t already being put to good use. Today, the rebuilt island is a nature preserve and bird refuge, teeming with life in its abundant marsh grasses. Once again, Poplar Island is an important gathering spot- only, its modern visitors sport feathers instead of straw boaters and neckties and spend their time making nests rather than brokering deals.

In honor of Halloween, a black and orange sunset paddle along Morgan Creek, off the Chesapeake’s Chester River. Fall is one of the best times to take to the Bay’s little coves and inlets by kayak- the geese and ducks cluster in floating rafts of endless chattering, and great clouds of migratory birds feast on the stands of wild rice that have ripened on the stalk. The early sunsets splash color lavishly, and challenge the vibrant leaves, which shade russet, gold, ruby, and bronze. It’s a magical season.

Perhaps the only ghostly specter is that of summer, which still whispers in the last few puffs of cattail, suspended like tiny ghosts over the collapsed salt hay.

A sign of the season- oysters, ready to be shucked, are left on a Ballard Oyster Company packing house table at breaktime. Some with sea lettuce still clinging to their shells, they were pulled from the water the same day they’ll be shucked into containers and readied for shipping. Oysters, packed tightly and kept cool, will be sent all over the United States to hungry consumers who are eager for the salty, creamy taste of the Chesapeake’s best shellfish bounty.

Three different kinds of crabmeat- good, better, and best. “Graded” crab meat (a brilliant marketing scheme) was developed by the Coulbourne and Jewett packing house around 1910, and their backfin, special, regular, claw and lump classifications became a signature feature of the enterprise. Located on the industrial waterfront area of Navy Point in St Michaels, Maryland, (today the grounds of the current-day Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum) Coulbourne and Jewett was one of the only African-American owned packing houses in the state- a remarkable accomplishment in the era of Jim Crow. Their savvy crab meat differentiation system would become almost universal in the industry- proof that all a salesman needs is a good product and the gift of spin.

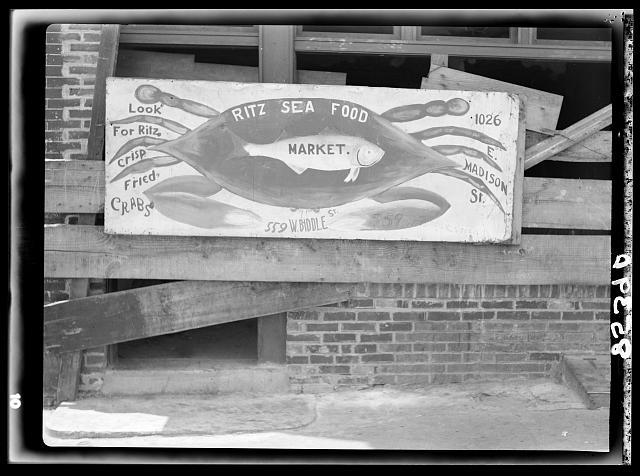

Crab Fisherman, Rock Point Maryland, Crab Sign, and Fishing For Crabs at Colonial Beach by Arthur Rothstein, 1919-1926. Collections of the Library of Congress.

With the crab population so precipitously low in the Chesapeake this year, some groups are calling for a moratorium on the crabbing harvest. Crabs are still an icon of the Chesapeake, and play a central role in our summer picnics and seafood industry, but the low harvests are driving prices up and raising concerns about the long-term future of the crabbing industry.

That said, it’s always nice to remember the good old days, when crabs were fat, plentiful, and cheap. These images from the 1930’s reflect a Bay that was still a vital resource- providing hundred of thousands of bushels of the prized delicacies, to be steamed in vinegar scented water and piled high with clouds of Old Bay.

A heavily clouded sky hangs above loblollies and the silver water of the Assateague Channel. This shallow, tidal salt marsh tucked between Chincoteague Island and the long tail of Assateague Island is the location of the annual Pony Swim made famous in Marguerite Henry’s Misty of Chincoteague. Barrier islands like Chincoteague, along the ocean side of the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia, are rich environmental landscapes, constantly changing because of shifting sediments, wave action, and erosion.

Scenes from Small Craft Festival- the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum’s annual fall celebration of messing about in boats. Small wooden sailing and rowing vessels are convened for a weekend in October by their passionate, dedicated owners- many of whom built the boats themselves.

Anyone, with the owner’s blessing, can jump aboard and take out different small craft, to see how they sail or navigate. St Michaels’ harbor, dominated in the summertime by massive yachts and large sailboats, is now full of small dinghies and skiffs that tack in the slow breeze with excited passengers calling back and forth. Fish school in the shallows and navigate around buoys marking makeshift moorings that have proliferated for the weekend’s events.

The parking lot turns into a campsite, as Small Craft participants take the party off the water in the evenings and swap stories and techniques and tall tales around a fire festooned with dogs and burgers.

It’s good old-fashioned Chesapeake fun- the kind people can still have, with a tenacious little skiff, a stiff breeze, and a full sail.

The "r" months- officially oyster season

An old-fashioned “r” month view. The location of modern-day Crab Claw on Navy Point in St Michaels, Maryland, 1907. Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

There’s an old saying around the Chesapeake: “you only eat oysters in R months.” These ‘R’ months (the coldest of the year, from September- April), are the Bay’s prime oystering time, as the delicious mollusks recover from their summertime spawn and fatten for the winter. Historically, as the seasons changed, watermen would store their crabbing gear away, readying their dredges, tongs and workboats for the icy, muddy work of harvesting oysters.

“R” months meant plump, sweet oysters- and they also meant less spoilage, as the cold temperatures kept the oysters fresher for longer once they were loaded into the decks of skipjacks, shucked into bightly-colored cans, and shipped north, west, and south, to a public clamoring for the Chesapeake’s oyster bounty.

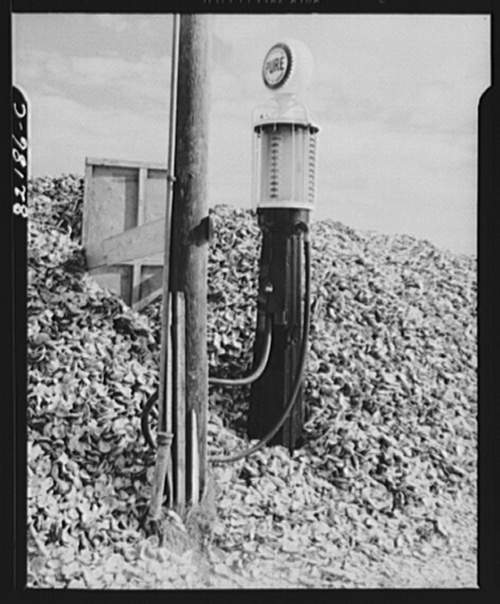

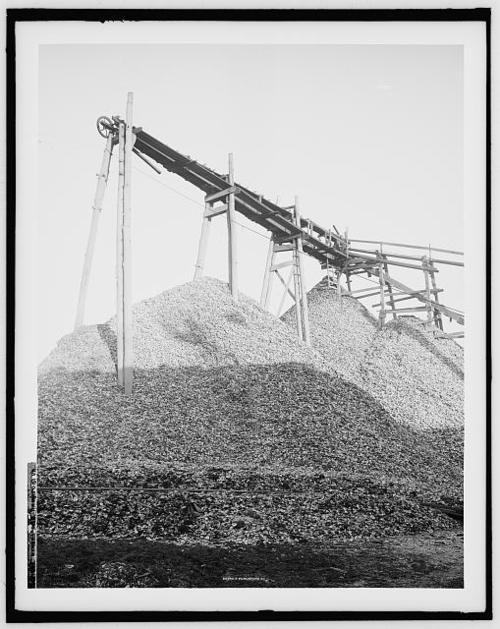

Another view of Navy Point, 1907. Collections Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

A sure sign of the beginning of the “R’ months and the real start to oyster season was the piles of oyster shells that would start to accumulate near packing houses in towns like St Michaels and Crisfield, where the oyster processors and cheek-to jowl log canoes jostled for real estate along the harbor front. By deep in the winter months, the piles could get several stories high- towers of shell testament to the mighty oyster, keystone of the Bay’s cuisine, culture, and the very stuff its small towns were built on.

Oyster shells, Dorchester County, 1930’s. Collections of the Library of Congress.

Oyster pile, Hampton, Virginia, 1915. Collections of the Library of Congress.

Three working ladies idle on their moorings during a Sunday afternoon on the Chester River. Normally all industry, these Chesapeake workboats stand at the ready for an early start on Monday morning.

A few early Canada arrivals enjoy the Havre de Grace sunshine at the Chesapeake’s Susquehanna Flats- famed wintering spot (and hunting Mecca) for migratory waterfowl.

A gloomy sky hangs over the graves of the 20 men and boys who died during the Starving Time at Jamestown colony during the winter of 1609-1610. A bleak chapter in Chesapeake history, the Jamestown colony ultimately succeeded unlike other settlements like the Roanoke colony- but scores of European settlers and native people would perish along the way.

Worth getting wet for- a kayaker swimming in American lotuses on a paddle along the Sassafras River. These native aquatic plants boast the largest blooms of any flower in North America, but lotuses are more than just a pretty face-most parts of the plant are edible. Their enormous leaves have also been known to provide shelter as a makeshift umbrella in Chesapeake summer thunderstorms.

Photo courtesy Bill Thompson.

An Interview with Chesapeake Photographer Jay Fleming

The Chesapeake Bay is an undeniably beautiful place, and it’s easy to take a photo that reflects the endless convergence of marsh, water, and sky. But the real challenge is to capture something that’s more than a pretty sunset. Jay Fleming is a young photographer working out of Annapolis, Maryland, who is hoping to change the conventional perception of the Chesapeake, one picture at a time.

From the traditional fishing culture’s slow disappearance as captured in the slumping collapse of the last house on Holland Island, to the vibrant eruption of silver croakers from a pound net (taken from the fish’s perspective), Fleming depicts a Bay that is working hard to keep its head above the water. Bursting with life, color, and dynamism, his photos convey the clear sense that the Chesapeake’s working harbors and underwater terrain are rich, thriving environments.

Clearsighted to the Chesapeake’s charms and its changes as only a native son could be, Fleming’s pictures look past the sunsets to a Bay that’s struggling to survive but still has so much magic left.

Following is the conversation of interviewer Kate Livie, Beautiful Swimmers blogger and CBMM education director, speaking with Jay Fleming, photographer.

KL: Who are you and how did you get started taking pictures?

JF: My name is Jay Fleming, from Annapolis, Maryland. I was born and raised in the area. My father is from Delaware and shot for National Geographic for 15 years, and I would go with him on assignments as a kid. As a teenager I started to use his equipment and when I was around 14 or 15, I submitted a photo to an EPA Wildlife and Wetlands photo contest and won the grand prize, which sparked my interest in wildlife photography and being on the water and taking pictures. I started shooting stuff I was interested in on the Bay and developed my own style that was different than my father’s.

KL: It seems like while some young photographers may expand away from the area where they grew up, you’ve really been dedicated to shooting the Chesapeake. What captures you about the Chesapeake, and why do you want to take pictures here?

JF: I would say that the more I look into a particular subject on the Chesapeake, the more I find out, the more I learn, and there are a lot of different photo opportunities for each subject. The thing I love about the Bay is that the deeper you dig into it, the more you find.

KL: What do you think is your favorite setting and topic to shoot on the Chesapeake?

JF: I love being on the water. I love fish, anything underwater. Watermen, different fisheries, underwater stuff. Those are what really spark my interest.

KL: Do you think your pictures tell a story, and if so, what is that story about?

JF: I think they do help people understand more, like the particular topic I’m working on now, which is how people make their living working on the water. I think my photos help people understand that the seafood industry might not be what it was 50 years ago, but there’s still a lot going on. There’s a quite a few people making a living off of the Bay and the Bay’s resources. If I can help people gain appreciation for local seafood and the hard working watermen, then I think that’s a great accomplishment.

KL: Do you feel like you are able to document the Bay in a way other photographer’s haven’t? What’s different about the pictures you take?

JF: I try to approach photos from a different angle than most photographers. I have the versatility of shooting above the water and underwater. I don’t think there are that many underwater photographers in the area, which I think you could say is my little niche. I have the ability to get out on the water, as well.

KL: How do you think your pictures help to address some of the issues that are impacting the Bay as it changes?

JF: My photographs are helping document what is currently going on in the Bay, whether it is a beautiful sunset or it be a dilapidated old building on the water, like the house on Holland Island. The pictures address a lot of issues that the Bay faces. I’m not trying to beautify anything, I’m trying to document what’s going on in the Bay, in somewhat of an artistic fashion.

KL: How do you think that your age gives you a different perspective or worldview on the Chesapeake than some of the photographers of the older generation?

JF: I see some of the things in the past that other people might take for granted, and I see how different ways of life and different communities are falling by the wayside with technology and this new generation. People aren’t really connected to the land like they were- not as dependent on the land. I think my pictures take people to a different place and a different time, also. The Chesapeake that once was, and still is, in a lot of ways. Kids my age don’t really get out a lot.

KL: How old are you, Jay?

JF: 27…Maybe I shouldn’t call myself a kid (laughs).

KL: But you’re a kid at heart, though, right?

JF: Always will be!

KL: Do you think your pictures might change any outcomes for the future Bay? When you talk about kids today that don’t get out, do you have a hope that they’ll reach people like that?

JF: Yeah, I do. I hope they can inspire people to treat the Bay better, and help protect the Bay, for the environmental purposes and the cultural purposes as well. Like with the watermen photos, a lot of people wouldn’t know half the stuff that I photograph actually happens. The people in DC and Baltimore and Annapolis might not know that people still go out in skipjacks and pull oysters off the bottom. They don’t know details about it. But being able to see it really brings it out in a different light. It’s still happening, and there’s quite a few watermen on the Chesapeake Bay. They’re going to hold onto their way of life and hopefully we can sustain it for the future.

KL: I think people tend to read the bad news in the newspaper and on TV and they begin to think the Bay is beyond all hope, but your pictures document how much is happening, not just above the water but below it.

JF: Absolutely. There’s a lot of negative publicity about the Bay, and the Bay has it’s fair share of environmental issues which have caused a decline in our fish stocks, but there’s still a lot out there that is pretty captivating and productive.

For more on Jay’s work, check out his online portfolio at: http://www.jayflemingphotography.com/

Thanks to Jay Fleming for the interview, and for allowing Beautiful Swimmers to share his images.