Throughout the Chesapeake Day, the icy, beautiful calm after the storm has created incredible, chilly vistas. Normally marshes that are a flat canvas of browns and greys in deep winter are golden and white, underscored by frozen high tide waterlines. Everything is silent except for the occasional crack of ice as hunkered-down Canada geese shift slightly in their temporary, transformed wonderland.

Image of Morgan Creek by author.

Louis Feuchter’s Chesapeake Bay

Skipjack and Steamboat by Louis Feucher. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

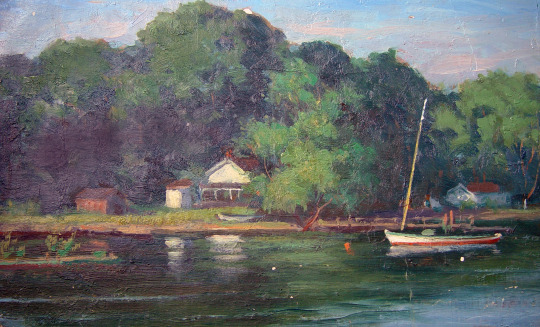

Some of the most captivating artwork in the collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is by a maritime artist, Louis Feuchter (1885-1957), who worked in the early 20th century.

Log canoe race by Louis Feuchter. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Feuchter was born in 1885 in the Patterson Park neighborhood of East Baltimore. At age 12, his talent was so promising that he won a scholarship to the Maryland Institute of Art, where he was formally trained in color, line, and technique, all deeply informed by the work of the late 19th century Impressionists. Feuchter went on to work as a silver designer for Baltimore’s renowned silver makers Kirk and Sons, and later worked as a sculptor, making clay models for decorative plasterwork. Laid off during the Depression, he lived the rest of his life in a tiny Baltimore rowhouse, caring for his ailing mother and creating art in a cramped bedroom.

Wharf and steamboat scene by Louis Feuchter. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

There were a few respites from Feuchter’s retreat into the confines of his little Baltimore house. During the summers, many of his happiest days were on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, when he vacationed at Wade’s Point near St Michaels. Maryland. There, a love of the Bay’s byways, landscapes and wooden boats was sparked that Feuchter would nurture for the rest of his life. Feuchter’s passion was ardent, but it was also well-timed. He captured the very end of the era of commercial sail on the Chesapeake, when

lumber, grain, and other goods were still carried to markets by schooners and steamboats. His

paintings depict with careful detail the world of the Bay in that last

of its working era, and the quiet beauty of Chesapeake coves that had

yet to be developed.

Eastern Shore waterfront scene, Louis Feuchter. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Feuchter seldom left Baltimore except for his summer jaunts to the Eastern Shore, traveling by steamboat. Exploring the small, working communities of the Nanticoke, Choptank and Miles Rivers, he found pastoral settings for Chesapeake boats—bugeyes, schooners, log canoes and more—that he documented in precise detail. Feuchter’s paintings conveyed the peaceful, humid stillness of the Eastern Shore’s waterfront communities, their impressionistic strokes recreating the solace of an evening at anchor. Sensitive and filled with light and color, Feuchter captured the Chesapeake’s many charms without sentimentality or nostalgia.

Bugeye and log canoe in a Chesapeake cove by Louis Feuchter. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

In 1929 Feuchter commissioned a small sailing yacht, a sort of miniature skipjack, from Eastern Shore boatbuilder George Jackson. He used the boat to sail away from Baltimore down the Patapsco River in search of rural settings for his paintings of Chesapeake boats, and his own boat became the subject of many of his works.

Chesapeake pungy schooners by Louis Feuchter. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum

One of Feuchter’s contemporaries, the photographer Hans Marx, wrote that he was, “a mild and unassuming man, with none of the airs you associate with artists.” Unfortunately, Feuchter’s softspoken demeanor may have been charming but it did little to bolster sales of his luminous paintings. His paltry income forced him to economize, and Feuchter often painted watercolors on scrap paper- old letters, bills or even calendars- to save money on costly canvas and oil paints.

Pungy schooner with full sails, by Louis Feuchter. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Feuchter had some successes during his lifetime. A friendship with Mariner’s Museum curator Robert Burgess lead to a series of commissions of ship’s portraits in oil. It was exacting work, and Feuchter excelled at capturing the precise details of each vessel type, from bugeyes to crabbing skiffs, corresponding frequently with Burgess and other maritime experts to get elements like reef points and trailboard colors exactly right.

By the 1950′s Feuchter’s mother had died, and alone in the rowhouse, his own health began to deteriorate. Feuchter was confined to quick sketches of animals in nearby Druid Hill Park. His paints were put aside, and other than a few paintings that hung inside his home, the gentle spread of the Eastern Shore’s meandering marshes was now just a memory.

A log canoe on an Eastern Shore cove by Louis Feuchter. Collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Feuchter died in 1957, leaving a legacy of work that represented the Chesapeake’s last days of sail. Serene, radiant, yet carefully detailed, his paintings evoke a Bay of beautiful, timeless simplicity. Elegant log canoes, burly bugeyes and saturated reflections of sky and trees wink like pennies in a wishing well, reminding viewers of what is there, just below the surface of the Chesapeake’s very near past.

The unusually warm weather has created some incredibly beautiful foggy mornings around the Chesapeake this week. This image, taken in Chestertown, Maryland, is just one example of the lovely way that fog, early light, still water, and the tangled architecture of wooden boat masts and rigging seamlessly intersect on these fleeting few dawn moments.

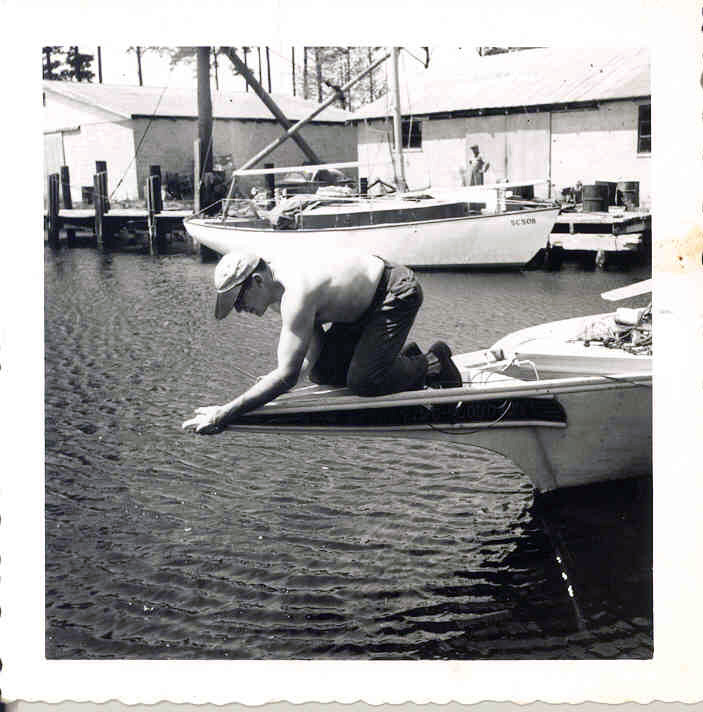

On a day that feels firmly sliding into winter, an image that is pure summer- CBMM’s new log canoe, Bufflehead, on the Miles River during her inaugural sail this summer on June 9th, 2015. No shirt required onboard, but a stiff breeze and a certain amount of devil-may-care adventurous spirit is critical.

Image by Tracey Munson.

Maryland’s Iconic Smith Island

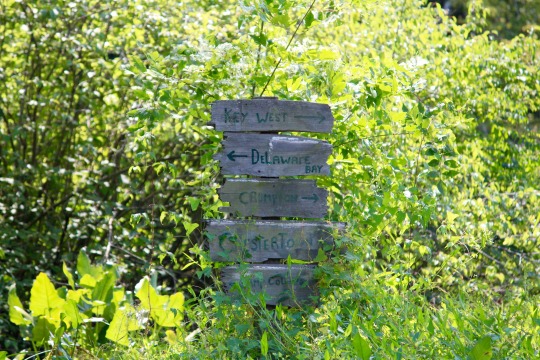

In the wide open waters of the Tangier Sound, a 30-minute ferry ride carries you from the closest town, Crisfield, to the classic charm of Maryland’s Smith Island. The low land is framed by endless water and sky, and the island is surrounded by thick, verdant wetlands roamed by egrets the color of bleached bone. Today, Smith Island is also home to a few hundred souls in several small towns that still largely rely on waterwork as the main economy.

240 residents live year-round in three communities of Ewell, Tylerton, and Rhodes Point— a significant drop from the island’s heyday when over 800 people lived on Smith and supported themselves well through the booming harvests of crab, fish and oysters. Today’s Smith Islanders, though less in number, still make a living from the Chesapeake—scraping for soft shells in summer and dredging for oysters in winter— but as the Bay’s environment declines, the number of watermen dwindles every year.

Mark Kitching is one of these watermen- in fact, he’s the head of the Smith Island Watermen Association. He grew up on the island and raised his family there, and acknowledges that though its a challenging place to live sometimes, we wouldn’t trade it for the world. Kitching loves the traditions on Smith Island, but he’s also willing to experiment— he and a partner have been growing a few thousand oysters on a new lease just a little north of where he docks his scraping boat. Unless Smith Island embraces some change, with new harvests or new kinds of people, he asserts, then the island won’t be around in 100 years.

Smith Island’s fisheries aren’t the only reason people are leaving the island. The Chesapeake’s insatiable tides have eroded away huge portions of the shoreline, and the Bay has rushed inland, inundating once-dry yards, homesites, and roads. The US Army Corps of Engineers estimates that in the last 100 years, Smith Island has lost 3,300 acres of shoreline, and scientists warn that the entire island could wash away as early as 2030. On the island, this truth is everywhere. Houses stand empty and abandoned, and stagnant pools collect beneath their mired foundations. Especially on the western side of the island, which bears the brunt of the erosion, once-handsome homes are quietly decaying into the marsh. Their paint peels and clapboard sags even as ornamental pomegranate trees in their jungly yards drop overripe fruit to the sodden ground.

But in each community, a nucleus of activity and life still thrives. Neighbors greet each other in the evenings on the streets where trucks without license plates haul fishing gear and golf carts trundle along. The Methodist Church is a community hub, busy with the goings-on of small town life from spaghetti dinners to funerals. Unleashed dogs roam in friendly packs as their owners enjoy constitutionals and greet each other. The one restaurant in town serves up mean soft-crab sandwiches and coffee, which some old-timers linger over around lunchtime.

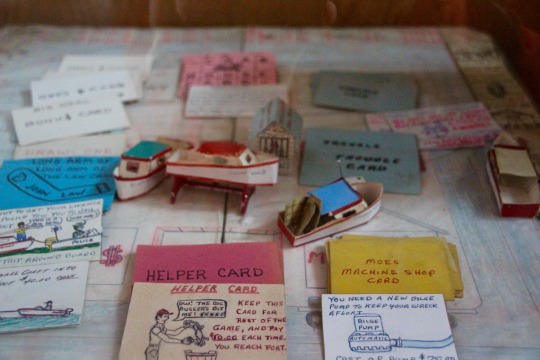

Over at the Smith Island Center, tourists watch an informational video about the history of the island, browse exhibits exploring the island’s traditions and former residents, and admire a custom set of ‘Crab-opoly’ created by a waterman one long winter, years ago. Tourism— from photographers, environmental types, students and weekenders— is a force on the island, although it is unsurprisingly seasonal. All summer long, visitors arrive on the ferry from Crisfield, ready to demolish a buttery crab cake at the Bayside Inn restaurant or a slice of the renowned Smith Island layer cake. Once temperatures drop, however, it’s back to a long winter of familiar faces and the occasional isolation of a deep freeze.

Small, friendly, and approachable, Smith Island is a place that represents the essence of what makes the Chesapeake unique. Life lived at sea level means one deeply connected to the Bay’s seasonality, its currents and its vacillating moods. It also has created a close knit community whose residents can rely on each other for a cup of sugar or to fix a workboat, yet still welcome outsiders with warmth and acceptance. These old-fashioned, small town values in a quintessentially Chesapeake setting are Smith Island’s most charming, resonant qualities— and fortunately, even hurricanes haven’t yet been able to wash those away.

All images by author.

Downrigging Weekend annually draws tall ship lovers from around the Chesapeake watershed to tiny Chestertown, Maryland. The waterfront, normally home just to the Schooner Sultana and a handful of workboats-turned-classrooms, now bristles with masts and rigging of visiting vessels from petite to behemoth. Each different ship, whether schooner, workboat or pleasure yacht, is a beautiful example of its type, and during the day, the docks teem with passengers eager to board and sail down the Chester River’s wide bends on these breathtaking boats. Even decidedly landlubbing-types can’t help but slow down to ogle the brilliantly-painted figureheads or glossy brightwork the gives a brief glimpse at the beauty and glamour of the Chesapeake’s seafaring past.

All photos by author.

Hey beautifulswimmers fans, the author of this blog, Kate Livie, has written a book! It’s the epic story of the long, tangled story of Chesapeake oysters- and their role as a survival staple, mainstay of the economy, and cultural catalyst. If you’ve enjoyed her posts on the Bay’s history, culture and the environment, it’s worth a look. You can purchase it on Amazon, or Maryland residents can grab a copy at local retailers or book events throughout the state. The Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum will be hosting a free book event for “Chesapeake Oysters” on November 20th at 5:00 PM- more information on that program is available at cbmm.org.

Happy reading, and as Kate would say, “Believe in bivalves!”

While log canoes are beautiful boats, the attention to detail in their smallest elements is really something special. This eagle carving and trailboard from the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum’s newest addition to the floating fleet, Flying Cloud, sparkle with careful carving and strong, glossy colors. As lovely as the best craftsmanship on a Philadelphia 18th century highboy, these decorative elements complete the poetry that is a racing log canoe’s elegant, lithe form.

Images by author.

In the late 19th century, the Chesapeake produced more oysters than any other region in the world. The oyster-packing industry was centered in Baltimore, and Roy E. Roberts was just one among scores of oyster packers in the city. To individualize their brands among such stiff competition, packers used distinctive names and imagery for their products to make them memorable to the consumer. Although Robert would later market most of his oysters under the “Maryland Beauty” brand, he briefly used the “Wild Duck” brand- making it among the rarest, most valuable, and most collectible oyster cans in the world.

R.E. Roberts, Inc., “Wild Duck Brand Raw Oysters,” R.E. Roberts, Inc., c. 1920. Lithograph on tinplate, 18.4 x 17.1 cm. Museum purchase, 2002.40.69. Digital image by David W. Harp © Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

On October 1st, Maryland’s oystering season opened again for another year. Currently, Maryland has 1,100 licensed oyster harvesters that will head out this winter from harbors around the state in search of bars full of mature, 3 inch ‘keeper’ Eastern oysters. Throughout the rest of the month, only a few forms of oystering are allowed: hand tonging, patent tonging, and diving. Power dredging begins on November 1st.

Traditionally, the “R” months (from September to April) have been the boundaries of oyster season in the Chesapeake Bay. Oysters spawn in the summer, making them milky and unpalatable, but in the colder months their efforts to turn growth and energy conservation, and they become the fat, toothsome morsels we love to enjoy half-shell or in stews, fritters, dressings, and all sorts of delicious ways.

Image by author.

This ethereal submission to our upcoming #cbmmsnapshots exhibition comes courtesy of Peter Lalor, who captured log canoe Island Blossom during a race on the Miles River in September. “Following log canoe fleet in Sunday morning race, in Steve Huntoon’s

yacht out of MRYC. The morning started sunny but by 11 there was a

lowering sky and very interesting light.”

To submit your own photos or to learn more about our upcoming Snapshots to Selfies: 50 Years of Chesapeake Summers exhibit, click here:http://bit.ly/1c2t2bT

Poplar Island, just northeast of Tilghman Island on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, is an otherworldly place. What largely comprises the island today is the result of an experiment of both environmental restoration and engineering on a grand scale. By the 1980′s, Poplar— an island that had once sheltered colonial settlers, farmers, hunters, and, as a Democratic retreat, presidents— had eroded away from 1,100 acres to just under ten. The rapid retreat of the shoreline displaced terrapin, shore birds and other species as well as humans from the island. Washed away by a hungry tide, the island was close to disappearing entirely.

In the 1990′s the state proposed a radical scheme- to restore the island with dredged materials. The concept was a boon for environmentalists, who mourned the loss of critical Bay habitat, and also for engineers who needed to keep the shipping access to Baltimore open. Construction began building in 1998, and the fragments of remaining island were built up with dredge spoils removed from the shipping channels approaching Baltimore. These materials were allowed to thoroughly dry, and were then planted with native grasses and shrubs. In this fashion, whole swathes of Poplar were reconstructed, one stage, or ‘cell,’ at a time.

Today, Poplar is a work in progress, but whole areas of the island have been restored—providing a glimpse of what the project might achieve by its completion date in 2031. Osprey nests stand sentinel over low, grassy meadows and scrubby upland islands where egrets crest on updrafts. Cormorants parade on a sunbaked shoal, their acidic droppings having scorched the soil into grasslessness.

As the island has been recreated in stages, one region may vary wildly from the ones surrounding it. In one cell, blooming marsh hibiscus as white as debutante dresses relieve a landscape of green. Just alongside it, dredge spoils crack in the sun on a newly-created moonscape of soil. It’s an environmental transformation on a monumental scale, slow enough to allow visitors to appreciate the behind-the-scenes atmosphere of an island in progress, but fast enough to see the changes from one year to another.

Trips to Poplar Island are free to the public, but need to be arranged in advance. To explore the island’s ongoing progress : http://www.mpasafepassage.org/poplartour.html

Every year, in late August and early September, the osprey begin their migration to their wintering grounds in the Caribbean and South America. Their piercing calls- the wild, carrying soundtrack of Chesapeake summers- falls silent as they wing away for another year. This fall, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation has created an osprey tracking map, so lovers of the “fish hawk” can watch the progress of two birds, Quinn and Nick, as they make their way to a warmer climate: http://www.cbf.org/ospreymap Though the birds are still in the Chesapeake at the time of this posting, no doubt the colder weather soon to come will encourage them to leave their summer nest and head south.

An osprey family at the approach to Poplar Island. Photo by author.

Headwaters

The mouths of rivers get all the love. They’re where you find watermen and pound nets, where it’s deep enough to swim and sail and maneuver a motorboat. They’re accessible and friendly and well-frequented.

But there’s a magic when you head upstream, an intimacy about the upper reaches of Chesapeake Bay tributaries. Shady, with still waters, these headwaters are remote and verdant. The houses built along the riverbank are far more modest than the stately homes found a few miles downstream, and sometimes just a few lawn chairs at favorite fishing hole are the only sign that people have been there at all.

Where rivers narrow, the chance at a close encounter with wildlife becomes increasingly likely. Herons squawk, outraged at being disturbed from their afternoon of fishing, and smaller creatures retreat into the underbrush, just slowly enough to be glimpsed.

It’s easier than it might seem to get lost as you head upstream. Many small tributaries connect to the larger river main stem, and each small branch has its own charms. Some may conceal stands of blooming marsh hibiscus, or streams where the water is so full of Bay grass and so remarkably clear that you feel like 400 years have suddenly slipped away.

The vehicle of choice on headwaters is small paddling craft. Canoes or kayaks- vessels that can thread the exquisite, jewel-like streams and needle deep into the twisting switchbacks and oxbows. The slow pace lends itself to closer observation of the river. Plants, birds, and small mammals can be seen at close range when a kayak quietly approaches. It’s startling, how much bigger a small stream seems when you’re on eye level with the landscape. A rare river otter, breaching out of the pondweed just past the tip of your paddle, seems as large and hearty as a Chesapeake Bay retriever.

Headwaters are where much of the Bay’s life begins, from the shad that spawn on the shallow, gravelly bottoms to the slender elver eels that lurk under submerged tree trunks. Thick with plants, narrowed almost to a tunnel, these marginal areas for humans are vibrant habitat for many plant species, which riotously proliferate- milkweed, cardinal flower, wild rice, pickerelweed, tuckahoe. These, along with the submerged meadows below the waterline, act as filters, absorbing nutrients, contributing oxygen, and settling sediment that runs off the higher ground.

As summer winds down, the open waters of the Chesapeake will crowd on the weekends, as people fit in that last fishing trip, that last sail to Kent Island or St Michaels, or that last day to run the river on a jetski. It is the perfect season to turn upstream, and seek the solace of your river’s headwaters. Cicadas, damselflies and water bugs will herald your arrival as you approach the heart of the Chesapeake itself. A river’s beginning, located centrally in the absolute middle of nowhere.

All images by author. Many thanks to Chesapeake Semester at Washington College’s the Center for Environment and Society, who acted as guides for this trip up the northernmost part of the Chester River

Not all Chesapeake watermen are actually men. This image taken by Lila Line in 1981, is a perfect example of the tenacity, tirelessness, and work ethic of plenty of the Bay’s water-working-women. While many women work off the water in watermen families, picking crabs or placing orders, some women choose to follow the example of their fathers or brothers, buy their own boat, and make a living from what the Bay provides. In this photo, Kathleen, a Tilghman Island waterman, is heading out for a long day of crabbing, despite being heavily pregnant. She continued to work until three weeks before her son, Noah, was born.

Image by Lila Line, collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

As these summertime shots from the 1920′s in Crisfield, Maryland show, not much has changed in 90 years about a Chesapeake Bay beach day. Cold drinks, crabbing, friends, ladies in bathing suits, silliness and big smiles are timeless hallmarks of a hot day spent cooling off in the Bay’s waves.

Images courtesy of John Sullivan.

Log canoe racing has long been a staple of Chesapeake summers. These races are the product of the late 19th century when recreational sailing was in its infancy, log canoes were transformed from their weekday use as workboats into fleet racing craft. Over the years, they’ve lost their use as oystering or fishing vessels, and instead have become the nimble vessels they are today— complete with enormous sails and hiking boards to carry human ballast.

1. “Flying Cloud” has her boomkin adjusted, 1958. 2. 19th century log canoe regatta postcard. 3. 1958 log canoe race, with “Magic,” “Flying Cloud,” “Jay Dee,” and “Mystery.” 4. late 19th century fishing party on log canoe 5. Log canoe race in Crisfield, Maryland, ca. 1922, 6. “Edmee S.” in race on Miles River, 2002. All images, collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Bounty of the Bay’s Bottom

This summer has been a particularly good one for the Chesapeake’s bottom grasses. Abundant and extensive, the underwater meadows are thriving this year, which is a good thing for the scores of species that seek shelter and food in the tangled masses.

Fish school around and through the patches of this “submerged aquatic vegetation” or SAV for short, and larger fish and crabs follow, snapping up the smaller species for dinner.

Widgeon grass in particular has seen a remarkable resurgence this year, and has largely contributed to the overall 27% increase in Bay grasses between 2014-15. Widgeon grass (photo above) has long, delicate leaf tendrils, and blooms in midsummer on thin white stalks. It’s great for vulnerable soft crabs, which hide in its shelter when shedding their shells until they’ve hardened up again. Widgeon grass is also excellent food for migratory waterfowl, which feast on billfulls of the tender grass strands. Scientists are unsure of why the widgeon grass has prospered this year— it’s a species that has irregular ‘boom or bust’ cycles, appearing and disappearing with little cause. But the expansion of the widgeon grass is a welcome sight, no matter the reason, and its presence benefits finned, clawed, and two-legged Chesapeake residents alike.

Mixed in with the widegon grasses are other species, and not all are native to the Chesapeake Bay. The Eurasian watermilfoil in the photo above is the most frequently-spotted example. With whorls of feathery leaves on long stems, watermilfoil creates dense clumps in slow-moving waterways. Accidentally introduced to the Bay in the early 20th century, it has proliferated and then attenuated several times in the last century. Although non-native, watermilfoil is not all bad. It provides habitat to Bay organisms, slows water flow and allows sediment to settle, contributes oxygen to the water, and thrives in places too muddy for native grasses.

The incredible abundance of Bay grasses this year is good for more than just crabs and fish. Grass beds provide prime crabbing and fishing spots, and within them, the water is often so clear and calm that one of the oldest and rarest of crabbing techniques is possible- the dipnet method. Armed with a dipnet, a bucket, and some luck, waders in the widgeon grasses slowly pass back and forth, searching for the elusive flash of brilliant blue claws. A cry of a triumphant, “I got one, Dad!” is the soundtrack to crabbing by dipnet, as families work together to fill a bushel basket for dinner.

It seems like time travel, back to a Bay 50 or 100 years ago, when crystalline shallows were an everyday sight and the Chesapeake’s bottom grasses were perennially verdant. Today, when so much is troubling about the Chesapeake’s environment, it is a remarkable if fleeting change of course. Bay grasses, for this year at least, mean clearer water, fatter geese, and abundant crab feasts— and the chance, for a little while, to see the Chesapeake your grandfather might have recognized.

All images by author. All rights reserved.

A summer’s day on the Miles River, as the skipjack HM Krentz sails out languidly towards the open waters of the Chesapeake’s Eastern Bay.

image by author

Tolchester Beach was a resort town in Kent County, Maryland in the late 19th and early 20th century. Established by the Tolchester Steamboat Company in 1877 and created wholecloth from what had formerly been several large plantations, Tolchester was a fantasyland of rides, games, music, and other diversions built on a bluff overlooking the northern Chesapeake Bay. Visitors could rent bathing suits, enjoy picnic lunches in shady groves, pilot electric launches around a small pond, and ride the wooden Whirlpool Dips rollercoaster. Day trippers or weekenders left Baltimore’s Light Street wharf early in the morning, and spent the 2-hour trip to Tolchester picnicking, enjoying the fresh breezes and taking in the Chesapeake scenery.

By the 1950′s, Tolchester had fallen on hard times. World War II saw many of the steamboats requisitioned for war use, and the opening of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge dealt the final blow as Ocean City became the resort destination of choice. By 1962, the resort, dilapidated and a shadow of its formerly-grand self, was formally closed to the public. It was demolished and razed a few years later, and a marina currently operates where the amusement park once stood. Today, all that is left are a few buildings, carefully saved and restored by a local man, Walter B. Harris, and some artifacts, carefully preserved in the collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

1889 Tolchester Beach poster, 19th century Tolchester postcards, and 20th century image of passengers on Tolchester Beach Wharf, Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum collections.