Getting to the Old Point

It’s the season of purpose for Old Point- built for winter use, it’s this time of year when the look of her, confined dockside and all her capability retrained, seems unnaturally harnessed. Old Point is a working girl, an example of a classic log built boat in the traditional style of vessel construction that owes its origin to the dugout canoes of the Chesapeake Indians, and was later adapted to the schooner form typical of 18th and early 19th century Bay vessels.

Old Point under restoration in The Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum’s working boat shop.

Sheathed within her hull are seven massive logs, weighty and substantial, creating a formidable backbone of strength and durability. Built in 1909 in Pequoson, Virginia, Old Point was intended to be a versatile workhorse, and when pressed to the primary task she was created for, Old Point weathered salt, ice, and bottom mud to harvest the lower Bay’s deep winter crab quarry.

Old Point, dockside. Late 20th century.

Old Point was referred to in her heyday as a “deck boat”, but today we call her by the job she was built for- a “crab dredger.” Crab dredging was a technique for harvesting crabs in the winter, utilized by Virginia watermen. The idea takes advantage of the natural migration of crabs, particularly pregnant females, as they descend from the grassy shallows of the upper Chesapeake to the saline-rich water at the mouth of the Bay for the winter months, awaiting the fertile pulse of spring warmth. Huddled all winter long under a thick comforter of bottom mud, these females hardly move once settled and as a harvest are similar to other bottom-dwellers, like clams or oysters.

It makes sense, then, that the tool watermen traditionally used for crab dredging looks very similar to its cousin, the oyster dredge. Their heavier construction (almost double the weight of oyster dredges) is built for mud rather than oyster bars, and two dredges at a time are pulled in tandem behind the crab dredge boat. Their long teeth biting deep into the Bay’s cake-like bottom surface, dredges root out the slumbering female crabs in long curls of sediment, under which they might be insulated as thickly as six inches or more. A good “lick” might unearth as many as 3 to 4 bushels of crabs per pass. The loaded dredges are winched back onboard and deck hands cull through the frigid bay’s bottom detritus, seaweed, sponges, clams, and other bycatch, sorting the keepers into barrels destined for market.

It was grueling work; dirty, and brutally cold, but it meant a steady seasonal income when not much else was running in the wide open mouth of the Chesapeake, and a small industry flourished around the harvest. Old Point would be one in a fleet of ten to thirty dredgers leaving the safe confines the harbor in Hampton, Virginia, between December and March. The sequence of dredge scraping, winching, and culling would be repeated on each of the crab dredgers dozens of times a day multiplied by thirty, in search of their catch, deep under the mud.

Old Point in the early 20th century, with crew unloading barrels of crabs.

20 barrels was the catch limit per day, but many crab dredgers had trouble achieving that amount- but not because of the crabs. Captain Ben Williams, a crab dredger on the East Hampton recalled to author of Beautiful Swimmers (the book), William Warner; “What’s missing are the variables. There are many. Gale force days when dredging is impossible. Ice. The bitter cold when the crabs are so deep int he mud that nine or ten barrels is a long day’s catch. Loss or damage of dredges, which last no more than two years in any case, and consequent time for repair or replacement. Then there are those mornings when the captain finds an empty bed in the tiny pilothouse. A crew member has had enough, quitting without notice, and a dredge boat cannot operate with only one hand."

From 1913 to 1956, Old Point was owned by the Bradshaw family of Hampton, Virginia. They made a living working the water on her, not just in the cold months when the harvest was hibernating crabs destined for she-crab soup, but in all the other seasons too- hauling fish on ice in the summer, transporting oysters from the hand-tongers to the market in the fall. But it was a tight living, eking out of an unpredictable Bay enough money for food, clothes and housing for a growing family, especially during the Great Depression. In an interview, a relative of the family recalled Captain Bradshaw’s anxiety over the boat: "At the beginning of every season, he would have a sick stomach, and throw up, and for about a week or two, he would be worrying about the onset of the next change in his year’s work. …Just as soon as the fish running starts, he going to be fine. That would always be the case.”

CBMM shipwrights stepping Old Point’s mast, summer of 2010.

As the crab population dropped in the 1980’s, days were numbered for old crab dredgers like Old Point - one of the first restrictions put on the harvest to encourage a recovery specifically protected females, especially sponge crabs, which can potentially contain as many as three million eggs.

Old Point’s log-built construction was another issue. She was relic from an era when boats were built solidly, to stand the test of water, weather, and wind; a bit of a throw-back as plank-on-frame and fiberglass construction were the norm. When she changed hands and no longer had a captain that could maintain her, it became harder to find boat yards that could work on her- or had the materials, if they could haul her out. After she was sold to the Old Dominion Crab Company in 1956, that old-fashioned construction lead to a new-fangled and slip-shod fix- a fire in Old Point’s bow left a hole that was hastily filled with Portland cement.

Old Point, summer 2012, Eastern Shore of Maryland.

After a short stint as an excursion boat in the Caribbean in the 70’s, Old Point was finally donated to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in 1984, where much painstaking labor has been put into reconstructing her as she would have appeared as a raw-boned working girl from Virginia’s roaring twenties. Today, she is one of only two log-hulled deck boats to still exist on the Chesapeake. Like a whisper of fog flung out over a still creek, Old Point’s long lines evoke a chapter in Chesapeake history that is just barely visible in recent memory. Days when the sun burning over an icy Bay meant money and security. When crabs could be brought up from the salty depths of an angry Chesapeake in winter, culled by hand until barrels brimmed over with hundreds desperate legs, and finally turned back to port and warmth, seven logs holding the captain and crew safe above the whitecaps.

An Oyster by Any Other Name

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. And for an oyster lover, a dozen on the half-shell, plump, cupped in their own vitality, are a lovely sight only to be topped by their taste. However, our appreciation is a fleeting thing. We toss them back at oyster bars until the empty shells clatter without a thought about where they came from or where they’re going. Other than mostly regional names we call oysters by to order them, we don’t wonder much about the mollusks we just consumed.

For the longest time in the Chesapeake, those regional names were a pretty short list, indeed- either ‘Chesapeake’ or 'Chincoteague’ (the distinction between the two was the milder taste of the former and the saltier tang of the latter). Other places might have 'Bluepoints’ or 'Appalachicolas’ or 'Wellfleets’, each oyster connoting a different point of supply and therefore a different flavor (or 'merroir’ as aficionados refer to it), but the Bay’s oysters were never really distinguished the way oyster varieties further North or South might be.

Some of the collection of oyster cans at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

That wasn’t from lack of trying- in the 19th century, during the height of the oyster boom in the Chesapeake, hundreds of packing houses established individual brand names and emblazoned them across thousands of metal cans, hoping to coax the public into purchasing their “Sailor Brand” or “Bevans” or “Honga” oysters. But none of these titles really stuck- and throughout the 20th century, when you ordered “Chesapeake,” you got “Chesapeake”- from any old spot in the Bay proper.

Choptank Sweets, grown just a little west of Cambridge, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

But that’s all starting to change, as the Chesapeake’s oyster industry grows to include aquaculture, a method of raising oysters by hand from spat to market-size. Much like agriculture on land, an oyster farm is a year-round process involving seed, crop management, eradication of pests, and a lot of manual labor.

It’s an approach that in most of the Bay is a new idea, but one that yields a predictable harvest (hurricanes notwithstanding) and a stable income. A handful of fledgling companies in Virginia and Maryland are having a go at the process, growing their crop in floating cages at the water’s surface in prime oyster territory where the oxygen is rich and the algae abounds. They grow their oysters, rather than wild-harvesting them, for a few reasons: aquaculture ventures aren’t subject to seasonal or catch restrictions the way watermen are, the oysters generally grow faster and larger in the cages, and with tending to keep them pretty and regular, aquaculture oysters are all ready for the more-lucrative half shell market.

Oysters in floats from the dock of Marinetics in Cambridge, Maryland

More oysters in the Bay are a good thing- for the environment and for the economy. One of the ways aquaculture ventures are looking to distinguish their oysters from their wild-caught Chesapeake competition is by naming them, like their New England and Gulf counterparts. These farmed varieties, which, as Crassostrea virginicas, are biologically identical to their brethren harvested from the Bay’s bottom, boast whimsical titles like 'Shooting Point Salts,’ 'Witch Ducks,’ 'Forbidden Oysters’ or 'Pleasure House Oysters’. Evocative of the Bay’s biodiversity, marshy landscape, and the silky, delicate flavor encouraged by the Chesapeake’s brackish water, aquaculture oyster industries hope to distinguish their particular bounty by appealing to all of a consumer’s senses.

Oyster aquaculturist Kevin McClaren on the dock at Marinetics.

The people of the oyster industry are a pragmatic bunch, whether working as watermen or as aquaculturists; don’t let the fancy boat or oyster names fool you. Kevin McClaren, aquaculturist at Marinetics, which produces the 'Choptank Sweet’ oyster, is no exception. He speaks plainly and knowledgeably about the process of growing and harvesting his oysters, and though he’s clearly an advocate of his own brand, he makes no bones about the work involved in the process and some of the hard decisions he’s made since the venture was started several years ago.

Kevin McClarin, aquaculturist, on oyster size from Kate Livie on Vimeo.

Since oyster farming with floats as a practice is still in its infancy, experimentation is part of the business. Whether to start from your own spat (baby oysters) or to buy it in from a lab, whether to go with oysters that reproduce naturally, known as 'diploids’, or get the sterile 'triploids’ that will grow much faster but not replace themselves, or even whether to grow your oysters on the top of the Bay in floats or to manage them on bottom leases instead: it all depends on your business, your location, and what you’re looking to produce. It’s still a wild-west industry, where innovation, a lot of sweat, and not a little self-promotion are key to success.

Kevin’s product, Choptank Sweets, are sold for the wholesale market, destined for restaurants and oyster bars throughout the Chesapeake. Raised on the water’s surface and fed with the natural plankton supply close to the to the waterline, his oysters grow much more rapidly than their wild counterparts 20 feet down or more. Within a year, some oysters can grow up to 3 inches- in contrast to uncultivated oysters, for which an inch a year is more typical. The faster your oysters grow, the faster you can get them legal size (3 inches) and to market, right- so that’s a good thing? Not according to Kevin- who explains that the quickly-grown oyster frequently has a thin, brittle shell, which is a nightmare to shuck and ruins the oysters for the profitable half-shell market.

Kevin McClarin, aquaculturist, on oyster size from Kate Livie on Vimeo.

As Virgina and Maryland legislation grows to encourage more aquaculture ventures like Marinetics, the culture of Chesapeake oystering will change to include these new, experimental techniques and technology. And as some of the shorelines of Bay tributaries slowly begin to encapsulate with oyster floats as protons hovering around their nucleus of docks and posts, new and experimental oyster varieties will accordingly proliferate on chalk-board menus- certainly a good thing for the centuries-old Chesapeake oyster fishery. Because for everyone that agrees that we all want more oysters in the Chesapeake- there are ten more people that agree that they want more oysters on their plate, whether they’re called 'Chunu’ or 'Watch House Point’, 'Olde Salts’ or 'Choptank Sweets’. Whatever you call their oysters, just don’t call their consumers late to dinner.

For more information on Marinetics and their brand, Choptank Sweets, check out their site here: http://bit.ly/XeOTSb

And this great oyster-lover’s blog, In a Half Shell , offers a fairly comprehensive list of some of the more established aquaculture brands in the Chesapeake, as well as further up and down the East Coast: http://bit.ly/X99N6M

Vanishing Landscapes

The Chesapeake today is just a thin skin of soil and time on top of the barely-concealed remains of the past. Old osage orange hedgerows, overgrown and serpentine, mark the field boundaries of the 18th century. Arrowheads and prehistoric shark’s teeth wash up regularly on beaches after a spring rain. And at the end of thousands of dirt lanes, overgrown and disused, old houses disassemble themselves.

Haden Hall, Long Yard

Though they might have been built at great expense, and taken years to construct, their demise is usually unceremonious. They fall apart, leaded windows cracked and shattered, sunshine streaming through the roof. Without people to shelter, their souls depart. They are giant, weathered headstones in a mown field of cornstalks, a silent witness to the life there a hundred, two hundred years ago.

Slave quarters at Poplar Grove

These images, by photographer and CBMM lecturer Shirley Hampton Hunt, are a testimony to the potency of decay- which, in the Chesapeake area, is an incredibly commonplace phenomenon, especially for old houses. Depending on the material and the age, the building may be a matchstick pile or seem to have barely suffered the depredations of time, but these abandoned places haunt almost every neighborhood, farm lane, and field. Their “everyday” quality does not diminish our fascination with them, however, for they are as full of questions as they are empty of people. Who built them? Who lived here and when? What would it have been like to live in this old house, walk these old floors that were once smooth? Why was this house neglected and forgotten?

Wickersham, Talbot County

It’s easy to imagine a house like Wickersham (which, since this photo was taken, has been moved to St Michaels and restored) in her heyday, and in your mind, the glass is replaced in the window lights, the steps extend from the front door to the grass, maybe roses bloom nearby. It’s a house that calls for a family- expansive enough for the people that built it and the slaves they owned, too. Looking past the slitted boards on the windows, they still seem present, if just in the atmosphere emoted by the brick and mortar. In places like Wickersham, they are so easily resurrected because they are thoroughly worn and shaped to human use, and even a long spell of decrepitude seems like just a temporary pause in their centuries of habitation.

The Guardian

Even if these remote dwellings and outbuildings are one lightning strike away from a pile of cinders and smoke, they still have a resonance. They convey so much about the Chesapeake that was, and create an significant aesthetic element of the Chesapeake that is. It’s a place where land and water, past and future are deeply and irrevocably intermingled. And under each sagging porch where raccoons hide, in every mildewed barn loft, behind the glass where the dead bluebottles are drifted, a part of that sense of place is captured and remembered, if with each day a little diminished as the wood and brick return to soil again.

Barn, John Powell Road

All images courtesy of Shirley Hampton Hunt: http://bit.ly/YjcJvz

The Marsh of the Future

A salt marsh near Chincoteague, VA.

There is nothing more quintessentially Chesapeake than a marsh vista. Over the horizon, the sunrise comes raging and the marsh is on fire: the stem of every reed distinguished in the burnished light, dipping and rippling, a mirror image of the brackish water below. Within this rich environment, only a few feet high, teems all manner and shape of life. Just a cursory glance displays the tiny, pulsing ribcage of a trilling spring peeper, the winking orange flash of a redwinged blackbird, the frantic wittering of all sorts many-legged insect swamp dwellers. Chesapeake marshes are the nursery of so much Bay life, and the livers, too, cleansing through a living grass filter the pollutants we shore folk flush, spread, cloud, and run off the watershed’s land mass.

Wetlands at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. (Adam Langley, SI)

Joseph Stromberg, from Smithsonian Magazine:

In a tidal marsh on the shore of the Chesapeake Bay, dozens of transparent enclosures jut above the reeds and grasses, looking like high-tech pods seeded by an alien spacecraft. Barely audible over the buzz of insects, motors power whirring fans, bathing the plants inside the chambers with carbon dioxide gas.

To scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) in Edgewater, Maryland, it’s the marsh of the future, a series of unusual experiments to simulate the effects of climate change and water pollution on a vital ecosystem. “What we’re doing out here is studying plant processes to predict the conditions of wetlands like this one—and tidal wetlands everywhere—in about 100 years,” Patrick Megonigal, a scientist at the center, says as he strides a boardwalk stretching into the 166-acre marsh.

The field study, stemming from an experiment first begun in 1987, is the only one of its kind worldwide that examines how multiple factors such as air and water pollutants will affect tidal wetlands—embattled ecosystems that will become even more important as a buffer against the storms and sea-level rise that are predicted to accompany global warming.

Made from PVC piping and clear plastic sheeting, each open-topped enclosure is a microcosm of a marsh under attack. Once a month, SERC scientists squirt nitrogen-rich water into the soil within the enclosures, replicating the fertilizer runoff that increasingly seeps into bodies of water like the Chesapeake. The plants are exposed to a carbon dioxide concentration roughly twice as high as that in today’s atmosphere; scientists have predicted that the higher level will be the norm by 2100, largely because of the burning of fossil fuels. The gas comes from the same tanks used in soft drink machines. “Our vendor tells us that we use more CO2 than Camden Yards,” Megonigal says of the Baltimore Orioles’ ballpark. “I actually calculated how many sodas that is, and it’s impressive: roughly 14 million 16-ounce bottles.”

Plants, of course, require carbon dioxide and nitrogen. But SERC studies have found, among other things, that some plant species grow more quickly when exposed to higher CO2 and nitrogen, while others show little response, a dynamic that could alter the overall makeup of the marsh. Still, predicting the consequences is tough. These excess nutrients boost plant growth and soil formation, which might counteract sea-level rise. But nitrogen also boosts microbe activity, accelerating the breakdown of biomass in the soil and reducing the wetland’s ability to serve as a carbon sink to offset carbon dioxide emissions.

Lately the researchers are examining a third environmental hazard: an invasive species. The tall, feathery grass Phragmites australis was introduced from Europe in the late 1800s through its use as a packing material aboard ships. In contrast to the native strain of Phragmites, the European version has become one of the most feared invasives in the eastern United States, aggressively displacing native species. In the SERC marshes, invasive Phragmites now covers 45 acres, roughly 22 times more than in 1972.

In greenhouse experiments, Megonigal and colleagues found that air and water pollution are a boon to the European Phragmites. With elevated carbon dioxide, it grew thicker leaves, allowing faster overall growth without any more water; with elevated nitrogen, it devoted less energy to growing roots and more to growing shoots. It was “more robust in nearly every plant trait we measured, such as size and growth rate,” Megonigal says.

In the chambers on the marsh, the Phragmites experiments look like a window into an unwelcome future: a perfect storm of climate change, water pollution and an exotic species poised to hit wetlands up and down the East Coast. A Phragmites invasion, Megonigal says, “has a cascading effect, with implications for food webs and the biodiversity of wildlife overall.”

Martha

Workboats are not normally things of beauty. They are built to be tough, capable, and versatile, to weather waves, tide, and wind. They reflect their use, their environment, and their purpose, and their battered white hulls are dingy with salt and a crust of bottom mud. Often they have cobbled-together parts- a car or tractor engine, scrap plywood floors, a gas tank fashioned from a metal casing washed up on shore. They are much used, and much appreciated, but as a breed designed for toil, workboat’s looks are not much fussed over.

There are exceptions, of course, to any rule, and Martha, a Hoopers Island draketail, is one of the most elegant workboats ever to slice through the chop on the Honga River. Built in 1934 in Wingate, Maryland by renowned boat builder Bronza Parks (whose sign over his workshop stated simply “Designer and Builder of Better Boats”), the Martha looks like a lithe debutante who’s been pressed into service in the water trade. Long and lean as a marsh egret and just as comfortable in the Chesapeake’s tidewaters, Martha was built to navigate and harvest the Bay’s great oyster and crab bounty. Great care was taken in her design and construction, which cost the princely sum of $250 during the Depression.

Martha, from the bow.

Martha was mainly intended for trotlining, a method of catching crabs using a long baited line in the water, with a roller on the side of the boat to pull the line up and over, and a dipnet to snatch the greedily feasting crabs from the line as the boat moves alongside. Trotlining was a fairly new technique for harvesting crabs, which only became a major part of the Chesapeake economy in the beginning of the 20th century as the oyster harvest declined. Sailboats were initially and rather inefficiently used to catch crabs, and even the next innovation, power skiffs with 2 cylinder engines, were awkward and not terribly well-suited for the purpose (watermen often had to drag buckets behind them to slow the vessel enough to work the line).

The long lines and rounded stern of draketails like Martha were a marked improvement- much better suited to the repetitive and slow task of trotlining, moving through the water with less eddies and a reduced fouling of the baited lines in the propeller. In the years before today’s modern crab pots were invented, her owner, Captain Willie Lewis, used the elegant Martha for threading the waters of the Honga River and beyond. Loaded with hundred of yards of line baited the day before and empty bushel baskets, he would head out from the protected harbor of Hoopersville long before dawn in search of Bay bottom teeming with the beautiful swimmers to be tempted to the water’s surface with salted eel or tripe.

Martha hauled for restoration, 1996.

The Martha came to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in 1983, and was restored to her original 1934 appearance during a restoration at the museum’s boatshop in the mid 1990’s. Her relaunch was an occasion for celebration, with members of the Lewis family and other watermen and boatbuilders from the Hoopers Island community in attendance. Memories of her captain, Willie Lewis, his family, and the crabbing glory days of the Eastern Shore during the early 20th century were revisited, with Tom Flowers, a Hoopers Island native officiating over the reminiscing:

“When Captain Willie finished crabbing in the morning (crabs drop off in the middle of the day), he would pull his baited trotline into the boat, usually onto the floor. As he returned to his dock he would bait the line with new pieces of eel or tripe. The old pieces of bait were thrown out and often a swarm of seagulls followed him home. Most of us who have trotlined usually developed calluses and cracks in the palms of our hands and fingers. When that salt would hit those open places, the pain, I can still recall.”

Martha’s working mornings of gilded sunrises breaking over the horizon on the wide open waters of the lower Chesapeake are over for good (as are her afternoons carrying a cargo of scrabbling crabs, salted eel and tripe). But her scrappy beauty, with its perfect harmony of function and form continue to poetically tell the story of watermen, crabbing and Chesapeake boatbuilding to all the visitors who explore the floating fleet at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. Martha today is one of the most evocative, arresting sirens from the Chesapeake that once was. It’s quite a legacy for a pretty girl from down on Hoopers Island.

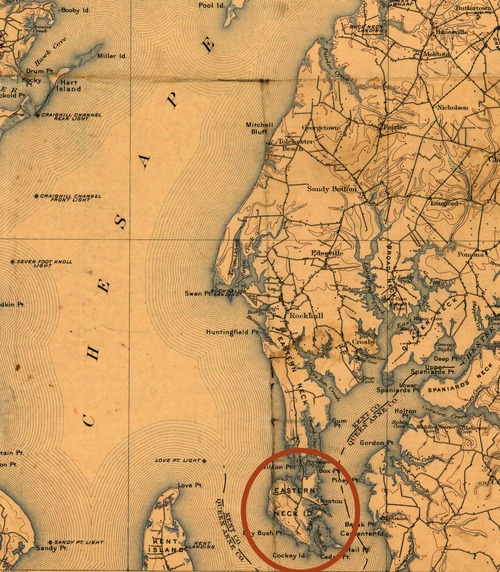

Eastern Neck- a Chesapeake Island

Where the mouth of the Chester River yawns wide to connect with the main stem of the Chesapeake, a roughly heart-shaped island stanches the flow of water as it disgorges into the Bay proper. Located at the very tip of Kent County’s southernmost peninsula, Eastern Neck Island is disconnected from the rest of the land by a thin tidal stream that grows more and less substantial with the wax and wane of the moon. The island itself is edged with billowing skirts of marsh grasses that waver with the wind, and inland, loblollies and hardwoods shade the interior’s thick layer of leaf duff. It is a beautiful place, an empty-of-people place, although it wasn’t always so. Eastern Neck Island, today a refuge for wildlife, was once a center of intense human activity. Like the Chesapeake in sum, the island has seen many versions of itself, revised by use, by erosion, by human hands.

It is winter the best showcases the uniquely Chesapeake gorgeousness that Eastern Neck Island embodies. As the island’s hundreds of acres of meadows and marshes turn ginger and rust, an incredible influx of waterfowl arrive to seek shelter in the island’s depopulated coves. Teals and canvasbacks, tundra swans and Canada geese all collect in Eastern Neck’s protected waters and as the sun sets, their clustered numbers turn the quiet island into a thousand-count conversation between goose, duck, and swan contingents.

A walk across Eastern Neck makes it easy to believe the island has never been influenced by people. Its trees tower, eagles circle high above on warm wind currents. Small creatures burrow noisily in the pine mulch, salt meadow hay lies in golden whorls, and cloven hoof marks are clearly impressed into the black mud along buzzing inland ponds. All seems as it evolved to be.

But it is only through the intervention, management and artifice of humans that Eastern Neck Island has achieved such pristine wilderness. Several iterations before its rebirth as today’s Chesapeake eden, Eastern Neck Island was a highly trafficked outpost of the Ozinie Indians, an Algonquian-speaking people connected through trade with the Powhatans, the Nanticokes, and the Susquehannocks tribes of the Western, Lower, and Northern Bay. The island, standing sentinel at the mouth of the Chester, afforded a perfect location for a seasonal people who sought the sustenance of teeming flocks of migratory waterfowl and the bounty of the great oyster reefs just offshore that could be waded to and plundered.

Today, parts of the island reveal the white, flaking remains of thousands of years of oyster dinners known as middens. These great mounded oyster discards now form bisque-colored beaches where delicate wafers of shell slowly recede back into the estuary that bore them several thousand years ago. Indications of favored Indian oystering grounds, the midden beaches are visual clues to one chapter of Eastern Neck’s oyster-laden history that has vanished from the modern day Chester River.

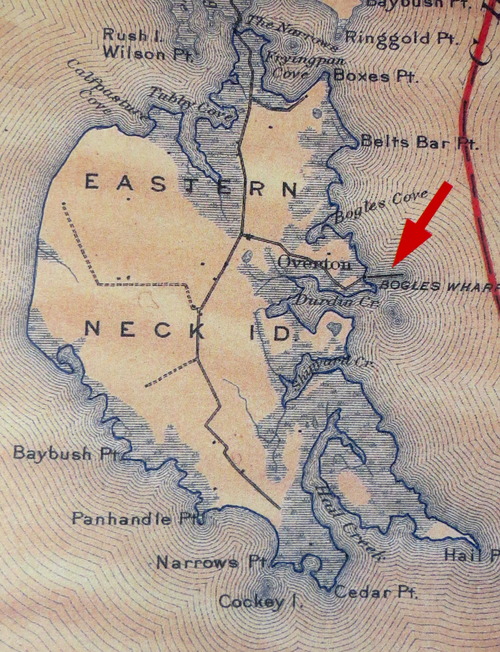

Oyster midden beach on Eastern Neck’s Bogle’s Cove.

During colonization in the early part of the 17th century, Eastern Neck Island, like Kent Island, was a choice location for its fertile soil, access to fresh water and plentiful game, and ready proximity to harbors with water deep enough for the draught of transatlantic sailing vessels. Two men in particular, Col. Joseph Wickes and his partner Thomas Hynson, coveted the island and sought to own it in its entirety, steadily purchasing tract after tract of land over a period of 12 years. The island’s forests were partially cleared, and fields of tobacco and wheat were planted. Wickes and Hynson were able to export their crop in vessels constructed of Eastern Neck lumber, in shipyards located on their doorstep. Houses made of fine red brick boasted of Wickes and Hynson’s agricultural and trade successes- “Wickliffe” and “Ingleside” were constructed in the center and the northwest portion of the island, respectively, and over the next 150 years they grew higgledy-piggledy, as Chesapeake houses did, with additions and cat slide roofs and gables. Other houses soon joined them, as the population of the island expanded to include slaves, craftsmen, shipwrights, and merchants.

Wickliffe, early 20th century.

By the 19th century, there were a few small towns on the island, basing their livelihoods on agriculture and the water trade. Overton was the largest, and was located near the steamboat dock known as Bogles Wharf. There were schools and barn dances, an oyster packing house. The water, and the abundance of life harbored in the islands coves and points remained the backbone of the community, and winter oyster harvests, spring shad runs, summers of watermelons and peaches piled high on buyboats, and fall with the vast numbers of waterfowl provided sustenance, income and security. A few hunting lodges were built in 1902 and 1930 to house wealthy sportsmen who only stayed during hunting season. So time would pass for a hundred years, with little changing beyond the the seasons for the inhabitants of the heart-shaped high land in the embrace of the Chesapeake and Chester.

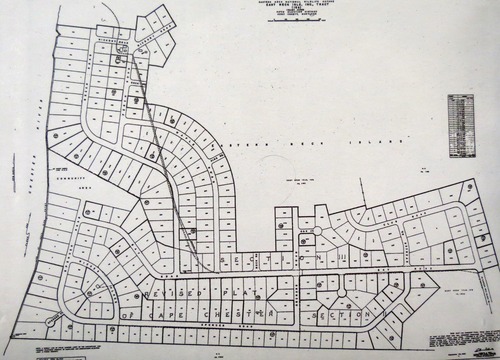

In this 1902 map of the island, the town of Overton and the wharf south of Bogle’s Cove is clearly marked.

During this era, William Dixon, a visitor in 1923, remarked, “…as far up the creek as one could see, was literally a mass of waterfowl, so thick, that it almost seemed one could walk upon them. I am not exaggerating in the least when I tell you-no history of the earliest records of the flight and congregation of waterfowl could have exceeded what we saw that day. There must have been hundreds of thousands-the very best of all our known varieties-Canvas, Red and Black Heads; intermingled also great quantities of geese and swan.”

Swans collect in an inlet.

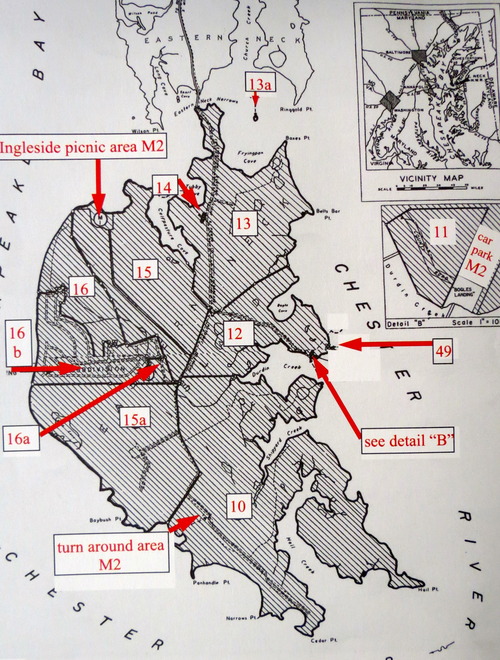

But change was on the horizon, as the Bay Bridge opened up the Eastern Shore to development speculators in the years following World War II. The country was booming, the economy was flush, and thanks to the mass production of personal yachts and sailboats, there were more people yearning to make their leisurely sunset over the Chesapeake a permanent fixture of their day-to-day lives. Places like Kent Island were being divided up and sold off in lots to newcomers to the Eastern Shore, who sought a rural lifestyle with the convenience of an easy commute to the larger cities on the other side of the Bay. By the early 1950’s, the scrutinizing eye of suburban progress had its eye on Eastern Neck’s open fields and loblolly stands, superimposing a grid pattern of over 290 lots where meadows and shoreline existed.

A map of the island shows the proposed development on the island’s western shore.

A closeup of the “Cape Chester” development.

An outcry rose against the proposed development, as it has many times since then on the Eastern Shore. The local population objected to the transformation of their Chesapeake eden into the banal landscape of sameness constructed extensively throughout the counties on the other side of the Bay. In particular, the rich habitat of Eastern Neck’s shorelines and marshes was threatened by the construction, which would have consumed hundreds of acres of salt meadows under tidy lawns and asphalt curbs. It was at this point that the federal government stepped in, acknowledging the island’s increasingly rare waterfowl habitat and ultimately approving Eastern Neck Island as a game refuge in 1962. Ironically, much of the public opinion at this point was against the refuge (for fears about it negatively impacting the property tax base), although the development concept had also been reviled. On the Eastern Shore, many have observed, no change is a good change.

Today, Eastern Neck Island is a stunningly beautiful trompe l'oeil of a Chesapeake wilderness seemingly untouched by plow, axe, or mason. On warm days, visitors in search of a patch of isolation in the midst of a busy world arrive, cresting the little bridge that barely attaches the island to the rest of the county. They walk their dogs under the oaks and beeches, skip stones over the tickling waves at the water’s edge, and bask in the lovely idyll that this little lonely bit of Eastern Shore could be all theirs, if only for a moment. But while its quiet expanses of pine savannah and waving plumes of spartina patens may seem utterly natural, uncontrived and uninhabited, all is not as it seems. Below a crust of oyster shells as thin as a teacup lip are the remnants of the people, the community, and the commerce that once dwelled here, and the ghosts of a future that almost came to be. The crockery of the island’s departed people, their obscured foundations, and their memories form the foundations of today’s Eastern Neck Island, a place where today, to quote Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Remains of the Bay

Just a few weeks ago, the residents of the Chesapeake huddled in their respective dwellings while the winds howled, the rains raged, and Hurricane Sandy pummeled the East Coast with furious tides that swept boldly inland.

Although many Chesapeake folks had prepared for the worst, stockpiling staples like toilet paper, water, milk, and Budweiser, for most of us within the Bay’s watershed, we were able to emerge relatively unscathed (though the contents of our refrigerators might have suffered rankly from the extended power outages). Given the appalling devastation just a few hours north, the Bay had gotten off pretty much scot-free. Or had it?

High storm surge tide on Hooper’s Island.Photo by David Harp.

Looking south, the Chesapeake ’s inhabited islands, Smith, Hooper, and Tangier in particular, are often observed to be bellwethers for the Bay’s eroding state of flux. In storms like these, where the wind and the waves scour the shoreline, up to 20 feet of land are lost annually and a canary sings sweetly from its coal-mine cage as the future of the Bay is written in the sediment washed away. Whole islands have been lost to the Chesapeake’s endless appetite, only to be reformed as sandbars or shoals somewhere else. It’s the Bay’s way.

Holland’s Island, now depopulated, still has some reluctant residents not anxious to seek higher ground. Photo by David Harp.

But these islands contain remnants of their human habitation that are not so easily removed. Even as the people moved away to avoid the water’s steady pull and the island’s shrinking perimeter, their houses, belongings, docks and yes, even their headstones and dearly departed remained. As strong ‘superstorms’ like Sandy flood the Chesapeake’s main stem with more and more frequency, things are bound to wash up on these Bay islands. And on Tangier, it wasn’t just old, corroded boat parts that got stirred up in the hurricane’s immense floods. It was the island’s previous generations.

If you ever needed a reminder that the the Chesapeake is a changing place, and of the visceral impact that shoreline erosion can have, this video is definitely it. In the end, it seems, some Chesapeake people indeed felt the wrath of Sandy’s power- they just happened to not be the living ones.

"The Boy, Me, and the Cat": this week in Chesapeake history

“Sport. The pursuit of pleasurable occupation which requires exposure to weather, exercise of all bodily muscles, judgment, skill of hand, foot and eye, never to be followed without a degree of personal risk. Under such classification I put Sailing of boats.” -Henry M Plummer.

The Mascot rounding up to retrieve its dinghy, which had severed its painter in rough water off the Potomac River.

100 years ago this week, on November 12, 1912, Henry Plummer, his son, Henry Jr., and their cat, Scotty, passed through the locks of the old Chesapeake & Delaware Canal in their catboat, Mascot.

Plummer, an insurance man from Massachusetts, was on his way southbound from Buzzard’s Bay in Massachusetts to Miami down the Intracoastal Waterway in the years before that inland passage was completed. He wrote about this adventure in the now-classic account, The Boy, Me, and the Cat, which was initially published in mimeograph form, with illustrations produced with a pin over the mimeo master.

Henry Jr. and Scotty, hard at work on Mascot’s launch engine.

Now travel on the ICW is routine- hardly the novel, book-worthy adventure it was in 1912, when recreational sailing was still in its infancy. But at the time, Plummer, Henry Jr. and Scotty were some of the first to brave the trip. While much has remained the same for modern travelers on the ICW (weeks of provisioning, eventful emergencies, and run-ins with annoyingly un-savvy sailors), the crew of Mascot definitely brought their own style to the trip. In particular, Plummer was idiosyncratically determined to ‘live off the land’ during the journey, taking shots from the boat with his .22 caliber rifle, “Helen Keller”. His son would later complain of dinners consisting mostly of unpalatable seabirds, with his father, clearly a proponent of the school of hard knocks commenting in his logbook, “Old squaw stew for dinner, and Henry had to run from the cabin, allow(ing) he would desert at Norfolk or right then and there if I gave him anymore sea fowl to eat. Foolish boy, he needs starving. Scotty and I finished the stew.”

Mascot at the Delaware and Raritan canal, before entering the beginning of their Chesapeake leg of the trip.

Plummer brought his story to life with vivid prose, a quirky conversational tone and lots of hand-drawn illustrations that have helped contribute to the book’s timeless feel. Now considered a classic of the genre,The Boy, Me, and the Cat may be 100 years old this week, but the nautical tale of a father and son braving wind, tide, water, and wildlife to complete the adventure of their lives still seems as fresh and current today as it would have to armchair travelers of the late Edwardian period.

Oysters on the rise

The extensive oyster selection at Portland, Maine’s Eventide oyster bar.

An article, titled “Oysters Ascendant”, in this weekend’s Wall Street Journal highlighted the bright environmental and economic future for farmed oysters in America. From Portland, Maine to Portland, Oregon, aquaculture oysters are booming in popularity- thanks to the emphasis on sustainable, slow food. As traditional sources of wild oysters are being negatively impacted by disease, overharvest, and in the case of the Gulf, oil, farmed oysters are taking their place in the fish markets and oyster bars of the United States. Customers pay premium prices for oysters of varying species and origin, seeking for that happy marriage of brine, algae, and oyster flavor that aficionados call “merroir” (with echoes of the ‘terroir’ referred to by oenophiles).

“Pemaquids” and “Glidden Points” on order at a boutique oyster bar.

Oyster connoisseurs often refer to the location of an oyster’s harvest (rather than their species) to define distinct characteristics about their taste, intensity, aroma and saltiness, from New York’s “bluepoint”, Florida’s “appalachicola”, to Massachusetts’ “wellfleet”. Chesapeake oysters, traditionally with only one specialized variety, “chincoteagues”, are now being differentiated and monikered by the up-and-coming aquaculture ventures that have proliferated in the southern reaches of the Bay. Consumers hungry for oysters of Bay origin now have the option of bellying up to an oyster bar and ordering a dozen half-shell “choptank sweets”, “watchhouse points”, “olde salts” or “parrot islands”, to name but a few.

The author as oyster oenophile- it’s all about the merroir.

Oyster consumers are largely driving these changes in the oyster economy, seeking a supply of shellfish that matches their demand for variety, quality, novelty, and sustainability. Aquaculture oyster growers meet those needs, offering oysters year round, continuously raising new generations of oysters to replace those sold, and harnessing the marketing appeal of a name whose cachet embodies place and taste. The Chesapeake aquaculture industry has certainly felt the impact of the demand for these 'boutique’ oysters- since 2007, the number of farmed oysters have exploded, with annual figures growing from 5 million to 23 million. Although most of the current Chesapeake industry is focused on the Virginia part of the estuary due to their traditional embrace of oyster aquaculture, the trend is growing in Maryland, as well, with the ushering in of legislation in 2005 that removed much of the red tape for oyster entrepreneurs in the state.

Boutique oysters also command higher prices than their wild-caught brethren, but rarely do they compete in the same markets, as many of the farmed oysters are destined for veritable 'oyster palaces’- specialty restaurants supplying named varieties of oysters arrayed on glaciers of mounded ice, serving half-shell to gourmand customers. Farmed oysters, with their smooth, tumbled shell, uniform size, and colorful appelations, are produced almost solely to meet these criteria of what is called the “half shell” market, where a premium price is commanded for a pretty, appealing oyster. Wild-caught oysters, on the other hand, are often destined for the shucking market, where the price per oyster is lower and their misshapen or barnacle-studded shells end up on the floor rather than a bed of ice and lemon.

It’s a sea change in the oyster market, and one that could easily change the face of oyster harvesting and populations in the Chesapeake over the next decade, whether you’re a consumer, a producer, or a waterman working the Bay’s bottom.

Interested in learning where oysters are being farmed, or about the trend for boutique oysters? Check out the Wall Street Journal article cited above, or take a look at In a Half Shell , a blog following the gustatory adventures of one young oyster connoisseur that features a comprehensive list that’s always growing.

Sink, Sank, Sunk

It’s not unusual, this time of year, to wake up to a cool Chesapeake morning that is pealing with the cracks of gunshots. So routine as to be background noise and so seasonal as to be synonymous with heavy frosts and the crimson stars of sweet gum leaves, the gunshots represent one of the great feathered influxes of fall fauna- it’s waterfowl time. For thousands of years, winged visitors from the sloughs of Saskatchewan and even farther north have moved in great v-shaped drifts to the Chesapeake’s verdant waterways as the cold weather descended. And for at least that long, people in the Chesapeake have eagerly anticipated their arrival and the full cookpots and bellies that flying feast represented.

Initially, the populations of the waterfowl that wintered in the Chesapeake were so prodigious that it was almost inconceivable that humans could ever alter the strength of their numbers. Colonist Robert Evelyn, exploring near the head of the Bay in the mid-1600s, saw a flight of ducks and estimated it at a mile across and 7 miles long, with the “rushing and vibration” of their wings sounding like a storm coming through trees. Creative methods were employed by winter hunters for generations to harvest this bounty. In the days predating the Migratory Waterfowl Act of 1918, when limits and regulations were established, gunners could shoot as many waterfowl as they wished, and so many of the early techniques and tools focus on sheer quantity in a way that is foreign to most sport hunters today.

Image from Walsh Collection, Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

One of the most ingenious watercraft designed for market gunning is the sinkbox- a coffin-shaped depression in the water surrounded by a low platform, weighted with lead decoys to float at level with the waterline. Meant to provide camouflage in the wide open waters of the Susquehanna flats, the sinkbox was almost imperceptible from above. Ringed with canvasback and redhead decoys, the sinkbox, with reclining market hunter inside, merged seamlessly with silver water, wispy fog, and grey sky to paint a perfectly Chesapeake (and perfectly deadly) trompe l'oeil. Recounting his days market hunting the Flats in 1878 in Harry Walsh’s The Outlaw Gunner, Bennett Keen recalled, “Our kill out of a sinkbox often ran to well over 100 ducks in a morning… We’d get maybe as much as $1.25 for a pair of canvas and as little as 25 cents for a pair of blackheads.”

Image from Walsh Collection, Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Hunting transitioned in the late 19th century to include the first generations of recreational gunners. A trend that mirrored the larger national craze for all things outdoors (the Boy Scouts, bicycles, and national parks all had their origins at the tail end of the 1800’s, too), hunting was a way for prosperous, middle and upper-class residents of Philadelphia and Baltimore to spend time along the Chesapeake connecting to their latent survival skills. Under the direction of a skilled guide, weekday office workers in natty new tweeds and stiff oiled canvas would track the canvasbacks waffling in with their shotguns poised, ready to reestablish their position on the top of the food chain with a single shot.

Image from Walsh Collection, Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Towns with access to the Susquehanna Flat’s superior gunning grounds, like Havre de Grace, swelled with city folk anxious to bag some birds come the opening of hunting season. Sinkboxes were favored above all other methods for their efficiency and success rate- although the sport gunners from out of town were a little soft to stay in them too long, recalled Keen in another excerpt from The Outlaw Gunner: “ For many years I capitalized on the desire of sportmen to shoot the celebrated flats in a sinkbox… I remember once my brother took out Grover Cleveland, and another time J. Pierpont Morgan. The hunters on the boat took turns in the box. If it was very cold they could only take an hour or so of it at a time; then they’d hold up their gun, a signal that they ‘wanted out,’ and to bring another hunter.”

Image from Walsh Collection, Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

The downfall of the sinkbox was the Migratory Waterfowl Act of 1918, which limited hunters to a sustainable, population-protecting rate of a few birds per day- far below the records of 200 to 300 canvasbacks or redheads a day during the height of the market hunting boom. Sinkboxes were notoriously cumbersome to set up- with rigs including hundreds of lead and floating decoys, corn and other bait, and sometimes even live birds to add an element of realism- and for only three or four ducks per day, it was a lot of work for a little reward. By the time they were outlawed in 1935, sinkboxes had already become a rare sight on the wide open water of the Flats- almost as rare as the canvasbacks themselves, which suffered a precipitous decline as their main food, aquatic Bay grasses, were buried under layers of silt as agriculture expanded in the 20th century Chesapeake.

Sinkboxes in the collections of the Upper Bay Museum.

Today, the only sinkboxes that remain are housed in private collections or museums like ours, where they represent the by-gone hunting traditions of the Chesapeake. But on a cold October morning, when the sun slips just over the edge of the horizon and the Chesapeake comes aflame with light, the fusillade of shotgun reports remind us that although the sinkboxes are gone forever, the hunting experience continues as fresh and timely as the day is young.

Bottoms up- there's an oyster in your cup!

“He was a bold man that first ate an oyster.” This quote from Jonathan Swift in 1738 has resonated through the centuries, largely because of its utter accuracy. Looking down with gusto into the cupped shell where the gob of living, wet mollusk lies, awaiting its trip down your gullet, is not for the faint of heart. There are plenty of other ways to consume oysters, however, if you need a few degrees of separation from their filtering little lives down on the Bay’s bottom. Stewed, steamed, fried, casseroled, creamed, sauced, frittered, and pickled- over the ages, we’ve developed a dish for every kind of oyster eater.

Feeling particularly bold?

The Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum has even had an oyster ice cream on offer at one of our festivals, thanks to a local ice cream innovator, Victor at Scottish Highland Creamery. (The author has unfortunately not had the chance to sample it, but the fact that it has not been added to their list of permanent flavors says it all.) But oyster ice cream isn’t the final frontier of culinary exploration using the oyster as the main ingredient. Recently, thanks to a partnership with Fordham Brewery, there’s an even more adventurous way to savor the flavor of Chesapeake “merroir”: a newly launched oyster stout, named after the Maritime Museum’s iconic skipjack, Rosie Parks.

The Rosie Parks Oyster Stout sounds radical, but oysters stouts are actually a brewing tradition that can be traced back to 19th century England. The middle of the 1800’s were oyster boomtimes not just for the Chesapeake but also for the British, whose oyster economy exploded thanks to preservation (canning, refrigeration) and transportation (steam locomotives) innovations out of the Industrial Revolution. Oysters were so ubiquitous and so cheap as to be an everyman food. In the Pickwick Papers, Dickens described the 19th century English oyster culture in this scene:

“It’s a very remarkable circumstance, sir,” said Sam,“that poverty and oysters always seems to go together.”

“I don’t understand, Sam,” said Mr. Pickwick.

“What I mean, sir,” said Sam, “is, that the poorer a place is, the greater call there seems to be for oysters. Look here, sir; here’s a oyster stall to every half dozen houses. The streets lined vith ‘em. Blessed if I don’t think that ven a man’s wery poor, he rushes out of his lodgings and eats oysters in reg’lar desperation.”

Oysters today are considered a bourgeois food, but in that era, oyster harvests were so high that even the humblest of incomes might afford them. Oysters were often served as a breakfast food, and came with another staple of the working man’s diet: beer, stout to be precise. Stout (essentially bread in liquid form) and oysters were considered a hearty, healthy way to begin a long day, and it was this classic pairing that lead to the original oyster stouts: beers named after the food they were paired with, rather than including oysters as an ingredient. The earliest oyster stouts, therefore, were the beers that you drank with your oysters, rather than the oysters that you drank in your beer.

Guinness is the classic example of a stout paired with oysters.

Image courtesy Brookstonbeerbulletin.com

But the two went together so well it wasn’t long before the idea of adding oysters to the beer itself bubbled to a head. Initially, it was only the shells that were used as a fining agent to clarify beer without filtration, reducing the bitter taste and softening the texture of the brew. Eventually, oysters with insides and all were added to the batch, with the earliest documented example produced by a brewery in New Zealand in the 1920’s. The subtly salty, briny marine flavor of the oysters complimented the rich, smoky notes of the stout, and oysters became a periodical addition to small batches of oyster stout (rarely is an oyster stout available all year long, much like the oysters themselves).

A batch of the Rosie Parks Oyster Stout is written up on the Fordham chart as it ferments, in preparation for its October release.

Today, a handful of enterprising craft breweries like Dogfish Head, Flying Dog, and Rogue have embraced the oyster stout seasonal style, with some including shells in the brewing process, and others using the oyster meat as well. Locally, though, it’s taken a while for Chesapeake oyster stouts to catch on- ironic, given the Chesapeake’s storied past as one of the richest and most prolific sources of shoe-sole-sized oysters (and their ardent consumers) on the East Coast. With Fordham’s launch of the Rosie Parks Oyster Stout, it would seem that the perfect audience for an elixir combining the Bay’s finest filter feeders and the roasted notes of malt is waiting with pint glasses primed.

Members of the Parks family gather to honor the liquid legacy of the Rosie Parks

The proof, as they say, is in the pudding- or in this case, the beer. Laced with the taste of the Chesapeake’s best oysters, the Rosie Parks Oyster Stout was rolled out to thirsty and appreciative tipplers at Annapolis’ Rams Head Tavern on October 4th. Just blocks away from a harbor that once teemed with the flaking white paint and salt-stained sails of skipjacks and bugeyes, laden with heavy cargo of the Chesapeake’s “white gold,” members of the family of famed shipwright Bronza Parks gathered to raise their oyster-flavored glass to the man that built the iconic skipjack the stout’s been named for. Oysters, stout, history and Chesapeake skipjacks- all happily married in a pint, with the proceeds going to support the restoration of one of the Bay’s last remaining workhorses. That’s one combination everyone wanted to raise (and drain) a glass to.

Want to taste some of the Rosie Parks Oyster Stout yourself? Come to Oysterfest on November 3rd at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, when it will first be served to the public! http://www.cbmm.org/oysterfest/index.htm

For more photos of the Rosie Parks Oyster Stout release party, click here: http://on.fb.me/URCcsA

Interested in some nitty gritty details about how Fordham makes the Rosie Parks Oyster Stout? Check out this video about how the beer was developed and recipe involved in making the stout below:

Cheers!

Postcards from the past

This weekend was the last calendar day of summer. But the signs of the transition to early autumn are everywhere- wedges of geese, calling high overhead, begin trickling down from the Great North; the slowed rasp of the crickets in the weeds; the movement of combines and big tractor equipment to the fields to reap the summer’s harvest. Even the air carries the copper-colored tang of decaying leaves and dry grass, gone to seed. These undeniable indicators of the end of summer’s halcyon days are bittersweet, and twinges of nostalgia for the long, sultry Chesapeake afternoons settle in once the summer’s end is just a few weeks gone.

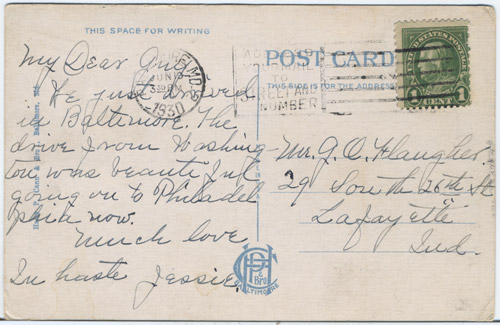

For a few generations, postcards were one of the ways best to capture summer like a lightning bug in a jelly jar. These colorful little travelling mementos fluttered from resort town to the folks at home during the summer high season, bearing cheerful sentiments and vibrant imagery that could be savored throughout the winter months. Functioning much like text messages do today (the style of writing was termed ‘postcardese’), postcards were meant to be brief but sweet, and often the message they bore was only a sentence or two in length. In contrast to the traditional lengthy missives, sometimes inscribed both horizontally and diagonally with text, postcards were a radical new form of casual communication in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“My dear Aunt, We just arrived in Baltimore. The drive from Washington was beautiful, going on to Philadelphia now. Much love In haste Jessie.”

While postcards made their debut in the 1870’s in the United States, they were slow to catch on- mostly because they weren’t very appealing. Initially, the US Post Office was the only entity in the late 19th century permitted to produced postcards, and the majority of these had no imagery, just space for writing. This regulation was lifted in 1898 when “souvenir cards” were allowed to be printed and circulated legally, opening the door to flocks of small rectangles of color and word that became faddishly popular. Postcards proliferated in popular culture, with pictorial mementos printed up of almost anything the Gilded Era could concoct- from vacation destinations, to national landmarks, to holiday sentiments, to cartoons and satirical novelty cards. Some were even a little racy (even if they don’t exactly look it, to our modern eyes).

Don’t look now, but there are women in the water with their ARMS showing in the daytime- scandalous!

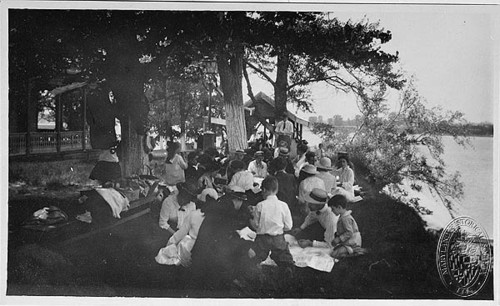

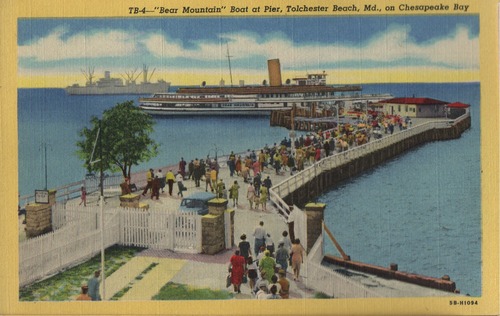

Mostly, postcards celebrated the everyday enjoyments of the era- travel, time spent with family, days at the beach, boat rides, carnivals, evenings listening to music. Of course, they represent an idealized slice of life, but in terms of communicating personal experiences, conveying a sense of the rituals of 19th and early 20th century social interaction, and documenting the trips and treats that comprised leisure time for the growing middle class, they are a treasure trove.

Tolchester Beach picnic Image courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society.

Here at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, we have hundreds of postcards from throughout the Bay’s numerous resort towns from the 1900’s onwards. Postcards from the era typically feature a saturated color spectrum, a vista of a summer scene, and throngs of folks whiling away their summer afternoons in yards of white linen and hundreds of straw boaters. Bearing brightly terse messages, these postcards help us better understand how a generation of bygone Chesapeake people enjoyed and remembered their experiences on the Bay. Unpacked from a dusty shoebox or exposed to the light of day when the pages of a disintegrating scrapbook are turned, these snapshots of an idyllic summer day, a hundred years ago, bring the full sensations of of the season closer for just a moment. And even when the nights cool, and the first brushes of rich claret tones touch the trees along the shoreline, those fond paper love notes to the past hold the warmth and fun of a day on the Bay, if only for an instant.

Blue Cats

As long as humans have lived throughout the Chesapeake, we’ve altered our environment. The Indians used controlled burns to reduce understory coverage below the soaring canopy and between massive trunks to allow for easier hunting. The first colonists slashed and burned their fields to cultivate tobacco, growing the seedlings in mounded hillocks around the charred stumps that were left behind. The 19th century saw the Bay’s bottom completely reshaped as thousands of years of accrued oyster reefs were demolished by the teeth of the dredges, pulled by sailing skipjacks.

Today, our changes to our environment are ever more obvious, and the footprint of their impact is as wide, deep, and extensive as the Chesapeake itself. The poster child is Phragmite australis, an invasive reed that uses disturbed marshes as its entree into an ecosystem, which has proliferated throughout the Chesapeake as humans have turned over swampland to create docks, lawns, and bulkheads. Now it waves gaily, a fronded impostor, welcoming passengers crossing the Bay Bridge to the Eastern Shore where its choking roots have stifled hundreds of thousands of miles of native marsh grasses.

Sure is pretty, though.

Below the dun-colored waves of the Bay are other non-native bullies, who arrived as released pets, or in ballast-water, or sometimes even on purpose. Snakeheads, the east Asian fish famously behind the draining of a Maryland pond in a failed attempt at eradication, are the ugly, snaggle-toothed face of the Chespeake’s aquatic invasives. Released into the pond by a man who had purchased a live pair in a New York Asian market where they were being sold for food, dramatic attempts at wiping out the snakehead proved fruitless. To date, 40 snakeheads have now been found in the Potomac River. There’s even an annual “snakehead catching contest” run by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources to encourage management of the species through recreational fishing. Snakehead control is also being promoted through the same thinking that brought them to the Bay in the first place: as a delicacy. Apparently, they make for some good eating.

Not all aquatic invasive species look so dramatically alien, however. Many can pass as native Chesapeake creatures, so completely at home are they in the Bay’s brackish environment. The blue catfish is an especially good (bewhiskered) example. They look and live very similarly to their relative, the white catfish, that evolved in the deeper tributaries of the Chesapeake. But at their largest, whites cats can grow up to 4 feet and weigh 50 pounds- which seems like a real Bay bruiser, until you compare them to the blue catfish whose maximum size tops out at 5.5 feet and scale-crushing weight of 100 pounds.

A fish that size needs an enormous amount of sustenance to maintain its energy as it silently cruises along the sedimented channels of the Bay’s bottom, consuming molluscs, insects, crabs, and fish with a ravenous appetite. Blue cats are such voracious predators, in fact, that they’re classified as “apex” predators- like wolves or lions. But in their native Mississippi River environment, they are surrounded by prey that has evolved defenses against the barbed behemoths. Here in the Chesapeake, however, these year-round residents hoover up humbler species, growing more fearless as they gain size and mass. Their endless consumption has hit certain Chesapeake fish hard- like shad, whose population has already suffered a major decline since the 19th century due to river damming, pollution, and overfishing.

A monster blue catfish, caught in the Potomac by a staff member from the District Department of the Environment.

Believe it or not, the blue catfish was purposefully introduced to the Chesapeake by the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries in 1977 to encourage recreational fishing. 300,000 small blue cats were released in the James, and over the next few years, several more nearby river systems were stocked. The blues took to their new environments with ease, quickly dominating the food chain with gusto. Their population increase was swift and expansive- within four decades, they’ve explosively reproduced, making up 75% of the fish in Chesapeake rivers like the Rappahannock and the James.

Blue catfish are monitored in Virginia through electrofishing.

Today the blue catfish makes up just one of the dozens of invasive species making their expanding mark of the Chesapeake’s forests and marshes, streams and channels. Some you can catch and control, some you monitor, and others you just watch as they silently replace the animals and plants that were once the trademark features of our environment. The Chesapeake has always been inarguably a changing land- but we residents of the Bay proper have ensured, since the first days that humans explored the piney woods along the shoreline, that the transformation would be continuous and complete. Who knows if hundred years from now, will we recognize the water we swam in, the fish that swim in it, or the land surrounding it? Once the cat’s out of the bag, the future is anything but clear.

For more on the blue catfish:

Chesapeake Bay Program- blue catfish field guide

Chesapeake Bay Journal- Blue catfish boom threatens region’s river ecosystems

Summer Drought, Summer Flood

Over the weekend, the heavens opened up and poured into the dry summer soil of the Delmarva Peninsula. The entirety of Sunday was a cacophony of thunder rumbles and lightning blasts, all underscored by the rushing patter of inches and inches of water falling. A fragment of a hurricane was stalled over us, and for hours, the furies of the weather continued unabated by an eye or a twinkle of sunshine.

From our little hill, in the slightly elevated part of the upper Eastern Shore, all was safe, if saturated. But an hour south, in Talbot County, some incredibly dramatic events unfolding, precipitated of course by the day’s seemingly endless precipitation.

Photo courtesy of the Talbot Spy.

In Easton, Maryland, just about the mid-point of the Eastern Shore, it was raining too- but in wet, wild torrents, that submerged the town in 8 inches of water and rising. Cars were stranded, with waves from the flooding runoff lapping at their windows. Drivers were rescued, as the town’s arteries surged and overflowed with rainwater that bypassed the usual storm drains and instead created temporary rivers where the traffic usually flowed.

Photo courtesy of the Talbot Spy.

Farther south, in St. Michaels (home of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum), the rain had also swamped the low-lying town. People gamely plowed through the rushing water, attempting (bravely or foolhardily, depending on how you look at it) to go about business as usual as if a foot of water wasn’t obscuring their passage.

This storm was certainly an unusual occurrence for the Eastern Shore- and particularly this summer, when much of the state suffered drought conditions and record-breaking temperatures for much of the sultry summer months. For weeks, it seemed as if the only sign of rain was the constant presence of a veil of humidity, softening the edges of the horizon with a suffocating wetness.

Smoky the Bear warned visitors at Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in Cambridge, Maryland of the heightened possibility of summer blazes in July. source

Thought the drought this summer has touched almost every corn field with its withering finger, there is a silver lining. For the Chesapeake Bay, a summer with hardly any rain also translates to a summer with almost no pollution. And when there is no pollution (read: fertilizer both animal and chemical, sewage, or exhaust), the dead zones in the Chesapeake shrink to a size not observed since 1983.

A 2005 chart of the Chesapeake's record high dead zones.

To translate, dead zones are simply expanses of water where the oxygen levels are not high enough to support life. They are caused when pollution, including nitrogen and phosphorous from fertilizers on lawns and farm fields, is washed by rains into the Bay, where it spurs algae blooms during longer, warmer summer days. When the blooms die off, bacteria that break down the dead algae consume oxygen in the water. Dead zones tend to be found in the Chesapeake’s main stem, where the runoff from rivers with high populations collect and merge (see chart above).The algae blooms that precede them can be green, brown, or even red, and often, though a harbinger of foul conditions, are quite beautiful from above.

An algae bloom in Hampton Roads, Virginia, in the Leehaven River. (Ryan C. Henriksen | The Virginian-Pilot)

This year, only 11.8% of the Maryland portion of the Bay had official dead zones, but normally the number is at least twice as high. It’s especially interesting since all predictions for this summer were dire. With 2011 Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee sending torrents of water and sediment coursing down the Susquehanna, through Conowingo Dam, and into the Bay, the assumption was the Bay this summer would be its least life-sustaining yet. But the extreme Chesapeake crisis was averted, though it was through an unpredicted but just-as-extreme summer drought that left many Bay farmers examining fractured soil and dried corn stalks for signs of life.

A Maryland farm field in July 2012.

In today’s modern Chesapeake, it takes a killing drought on land to restore balance below the water. Simply put, that’s the definition of unsustainable- and on a scale that seems to huge as to be insurmountable. But this very question of restoring balance to the Chesapeake, especially when the effects are so visibly obvious, hasn’t deterred or dispirited advocacy at all. Rather, the Chesapeake’s distress has become a lightning rod for innovation- and most of it is humbly human-sized. From oyster restoration to cover crops, organizations and individuals throughout the watershed are cooking up potential solutions to the problem that can be addressed by one person at a time. A great illustration of this outpouring of ideas is summarized, for a youthful audience (though we can all benefit), in Sunday’s Washington Post: http://wapo.st/Nm0oWH

The flood we endured this weekend was one of torrential rains, but the flood we need is one of ideas, to help create a Chesapeake we can all live in, whether we farm, mow, garden, swim or filter. Sometimes it takes a deluge, a profound drenching that swamps our cars, our yards, and our complacency to remind us that we still have a lot of work to do, if we want to take care of this place we call home.

Dinosaur fish

Down in the swirling sediment of the Bay’s bottom, an ancient creature combs the sand for small sea life to consume. Its bottom-feeding mouth descends from its jaw as white and elegant as a a lady’s elbow length glove unrolling down a slender arm. Sturgeon like these, holdovers from the era of the dinosaur, are mammoth reminders of a Bay where the scale of everything- fish, trees, predators- was once much, much larger. Plated beneath their tough, starburst-patterened skin with scutes, hard bony armor that protrudes along the fish’s belly and back, sturgeon seem perfectly suited for a Chesapeake where what was under the water was just as fierce and massive as the things that dwelt above.

There are two kinds of sturgeon that have lurked in the Bay’s channels: the shortnose sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum) and the Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrhynchus). Both grow incredibly slowly, but can attain a size of (in a few stunning examples) 15 feet or more, and over 800 pounds. They also are not quick to replenish their stock, as the females take almost 20 years to mature. But in the Chesapeake of millennia past, that hardly mattered. Their gargantuan size meant that they had almost no natural predators when they returned to the Bay twice a year to spawn, and the small mollusks, crustaceans, and other benthic organisms they hoovered off the Bay’s bottom were richly abundant. Sturgeon could originally be found in all of North America’s Atlantic tributaries, and in the fall and spring, courses of them moved along the rivers that connected to the ocean, occasionally breaking the water’s surface with a mighty thrust skyward.

As long as there have been people living along the Bay’s tideline, the residents of the coves and inslets of the watershed have been subsisting off of the living Chesapeake cornucopia. Sturgeon, of course, are no exception, especially considering the sheer mass of food provided by the capture of just one fish. The first Chesapeake people to land sturgeon were Indians, as evidenced by archaeologist’s findings of enormous scutes still haunting their ancient trash pits, known as middens. Early colonists described the daring technique the Native Americans traditionally used to captured the sturgeon:

“The Indian way of Catching Sturgeon, when they came into the narrow parts of the Rivers, was by a Man’s clapping a Noose over the Tail, and by keeping fast his hold. Thus a Fish fmding it self intangled, would flounce, and often pull him under Water, and then that Man was counted a Cockarouse, or brave Fellow, that wou’d not let go; till with Swimming, Wading, and Diving, he had tired the Sturgeon, and brought it ashore.” Robert Beverley, 1705.

Given the lack of an Algonquian written language, the only accounts that exist to describe the enormous fish are from the first wave of colonists. John Smith, in particular, wrote often about sturgeon and its roe, which were a familiar luxury food in Europe and therefore quickly became a regular part of the meager diet for the colonial transplants. But even the most savory delicacy will lose its appeal after weeks on the menu, and as the Jamestown settlers had little else to sustain them, they soon got creative with their sturgeon meals:

“We had more sturgeon than could be devoured by dog or man, of which the industrious by drying and pounding, mingled with caviar, sorrel, and other wholesome herbs, would make bread and good meat.” John Smith, 1608.

Smith also described the abundance of sturgeon during the first few years of European settlement in the Chesapeake:

“In summer no place affords more plenty of sturgeon, nor in winter more abundance of fowl, especially in time of frost. There was once taken fifty-two sturgeon at a draught, at another draught sixty-eight. From the latter end of May till the end of June are taken few but young sturgeon of two foot or a yard long. From thence till the midst of September them of two or three yards long and a few others. And in four or five hours with one net were ordinarily taken seven or eight; often more, seldom less.” John Smith, 1608.

As the surge of colonists continued, sturgeon remained a staple of the diet in the tidewater for the newcomers as they fanned out across the watershed to establish tobacco homesteads on remote creeks and rivers. There were also hopes that sturgeon could be an early driver of the colonial export engine, with the flesh, the caviar, and the oil packed and sent back to turn a hefty profit in Europe, where the overfished European counterpart was already commanding a princely sum. However, preservation was inadequate, and the arrival of barrels of spoiled fish at the docks in London ensured Chesapeake sturgeon wouldn’t take off internationally for several centuries.

Sturgeon being processed dockside, 19th century.

By the 19th century, with technological innovations during the Industrial Era, preservation techniques had made great strides forward, and almost overnight the fisheries along the East Coast boomed as millions of mouths suddenly had the opportunity to buy preserved fish, far from the ocean. Sturgeon was no exception. Initally, harvests were high and the flesh, skin, caviar, and oil was exported internationally to enormous profits. Even the swim bladder was used to create isinglass, a gelatinous material used in confectionaries, and to clarify beer and wine. But given the ponderously slow rate of sturgeon growth and reproduction, the boom didn’t last long.

Sturgeon at a Maryland dock, 1901.

“Catch records from the 1880s show a great abundance of Atlantic sturgeon; with catches of 17,700 lbs from the Rappahannock River, 51,661 lbs. from the York River and tributaries, and 108,900 lbs. from the James River. However, by 1920, the catch of Atlantic sturgeon for the entire Chesapeake Bay amounted to only 22,888 lbs. and the fish was considered scarce (Hildebrand and Schroeder 1928). By 1928 Virginia had enacted a law asserting, "that no sturgeon less than 4 feet long may be removed from the waters of the State” . The Chesapeake Bay Atlantic sturgeon fishery continued to harvest fish, but at a fraction of its previous rates.“ source

Sturgeon continued to make rare photo-worthy cameos in Bay-area fish shops throughout the 20th century.

Today, the sturgeon fishery is completely closed in the Chesapeake, as it has been since 1997. Due to overfishing, the creation of dams that block their spawning habitat, and the decline of the Chesapeake’s water quality, sturgeon are incredibly rare in the Bay (with the majority of the remaining population found in the James River or occasionally in the Chesapeake’s main stem). This February, Atlantic Sturgeon was even classified as an endangered species. But it isn’t too late for the dinosaur of the Chesapeake deep. In Maryland, an environmental research center in Cambridge is working on spawning a solution to the sturgeon’s population problem.

Sturgeon fry from an experimental stock raised to replenish threatened Bay populations.

Hundreds of tiny sturgeon are raised at Horn Point Labs every year. A satellite campus of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, these Horn Point sturgeon are destined to be raised and studied for information about sturgeon reproduction and growth, and ultimately may provide part of a restoration, along with water quality and habitat improvements. Until then, you can get up close and personal with these lingering remainders of the dinosaur era through the webcam at Horn Point’s laboratories here. Watch these primordial sturgeon and imagine a Chesapeake where the water ran deep and clear, and longboard-sized giants like these cruised the arable meadows on the bottom, plucking their meals delicately from the sandy substrate.

A Buyboat Returns to the Bay