Kayak Scenes

There has been much written about the magic of sailing the Chesapeake Bay. Wide open water, slightly salty note in the humid air that strokes your face like a silky palm, and fills the sails. Harnessing the elements of the Bay’s brackish tide, bound for Reedville, St Michaels, Annapolis, or destination unknown. But there is another, more intimate way to connect with the engorged tidal coves of the Bay’s thousands of miles of shoreline: by kayak.

Kayakers are tourists on a surgical scale. They explore the twisting oxbows of shallow Chesapeake tributaries in a precise, minute fashion alien to the racing speeds of sailors and power boaters. They amble. They prog. Their behinds are sodden with the tannin-rich water of the hardwood canopy streams, and they have pollen in their hair from dusting along ripening chaffs of wild rice. They are getting nowhere fast, but somehow, the aimlessness itself is the journey- there is so much to see.

Sounds, amplified by proximity, make up an essential element of the landscape at the kayak level. It is a noisy place, these Chesapeake marshes. Red-wings blackbirds cry out in a trilling melody as they sway back and forth like a metronome from the tops of frothy cattail. Osprey chirp, silhouetted by the sun, angling for their supper from a cloud-level vantage point. Bullfrogs belch out some bass notes that will echo as the sun sets and the mosquitoes teem. Every creature, it seems, vies for the spotlight in this backwater stage. It’s supposed to be peaceful, but people think the city can be peaceful, too. In their own way, these creeks are just as bustling, their din just as ceaseless as a metropolitan center. Traffic streams silver down the rivers, raptors substitute for airliners, and insects crowd on tuckahoe leaves like bargain hunters at a flea market.

Kayakers often liken the landcsape they enjoy to a “John Smith” view. Meaning, as untouched, pristine, and unspoiled as the 1607 Bay that Smith explored on his forays from Jamestown. And though much has changed- the bottom is siltier, the water cloudier, the plants pushed aside by non-natives, the crabs and otter confounded by the blue catfish and the nutria, there is much that feels unchanged. Little development has reached these shallow, isolated creeks and streams of the Bay’s tide line. Heron rookeries aren’t uncommon to discover, or beaver dams as wide as a two-lane dirt road. Abandoned houses, half covered in scuppernong vines with glassless windows, stand sentinel along the shorelines. Their fragrant sweetheart roses still perfume the air, unaware that the scenery has changed since the 1920’s. By kayak, the Chesapeake can feel like the world has ended and you are the only person left in the vast wilderness. It can be eerie, but is is generally a good feeling.

But even better are the paddles shared with others, where you raft together and point out all the incredible things to see with too many legs, scuttling away in the sand. You share the sunset like a heaping plate of food until you paddle back home, satisfied and kingly. To paddle around in a low vessel is a slow moving method of exploration, as John Smith well knew, but its also a way to observe and savor the Bay’s heartbreaking beauty both intimately and together.

When you need a reminder that the Bay isn’t done for, and those dead zones they keep talking about on the news aren’t the last word, put some bug spray on and find some shorts that can see a little mud. We’re going for a paddle tonight.

“House in Negro section of Baltimore, Maryland." July 1938. Medium-format nitrate negative by John Vachon. For a larger version: http://bit.ly/1sqTn73

After a sweaty-palmed trip over the long Chesapeake Bay Bridge, many beachgoers make habitual yearly stops on their annual exodus to Ocean City at many of the crab houses on Kent Island. But they weren’t always massive waterfront establishments with gorgeous views of loblolly islands and watermen coming and going. As this photo reminds us, the original "crab houses” would have been the kitchen in a private home, where a local lady made some extra cash by cooking up and serving crabs to her hungry neighbors. In the sweltering belly of a Baltimore summer, the smell of a proprietary blend of spices would have clouded in the humidity, a savory London fog and invisible shop sign. Crabs, clams, fried or cakes wrapped in newspaper, all to be carried off and eaten on a quiet stoop with salty fingers and a glowing, greasy chin.

YMCA Camp Pawatinika

Anne Arundel County, Maryland

circa 1929

Unidentified photographer

4x5 inch glass negatives

A. Aubrey Bodine donation

Baltimore City Life Museum Collection

Maryland Historical Society

MC7913 .1

MC7913 .2

MC7913 .3

Any waterman will tell you- sometimes the best action happens away from the dock! This yellow lab takes an unsupervised opportunity to get up close and personal with a striped bass (or rockfish, to us Chesapeake people).

Photo courtesy Walt Hubis, flickr: http://bit.ly/1hhozi7

Not too much has changed about a summer’s day spent on the Chesapeake- except, perhaps, for the bathing suits! Wool one-pieces like these worn by Virginia bathing beauties in 1910 were considered modest as well as “healthy” (the wool was thought to keep the swimmers warm). It’s no surprise, however, that drownings occurred frequently as a result of the voluminous costumes.

While we may not always relish the imminent arrival of bathing suit season and the subsequent exposure of our winter-plumped figures, its clear that things have certainly changed for the better, where swim suits are concerned!

From the collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

For more on the history and changing hemlines of the modern bathing suits, check out this great post by Consuming Cultures: http://bit.ly/1jH5Jl6

Fishing for gudgeons

Patapsco River, Maryland

1929

A. Aubrey Bodine

4x5 inch glass negative

Baltimore City Life Museum Collection

Maryland Historical Society

MC8254 B, D, Q, R

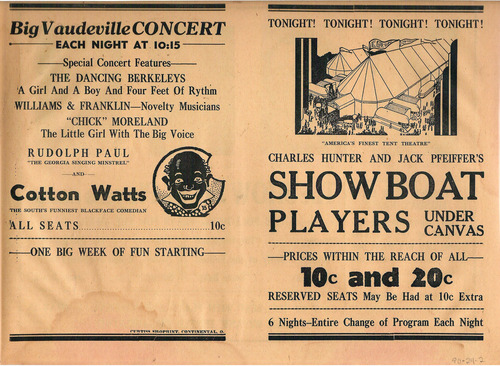

The James Adams Floating Theatre

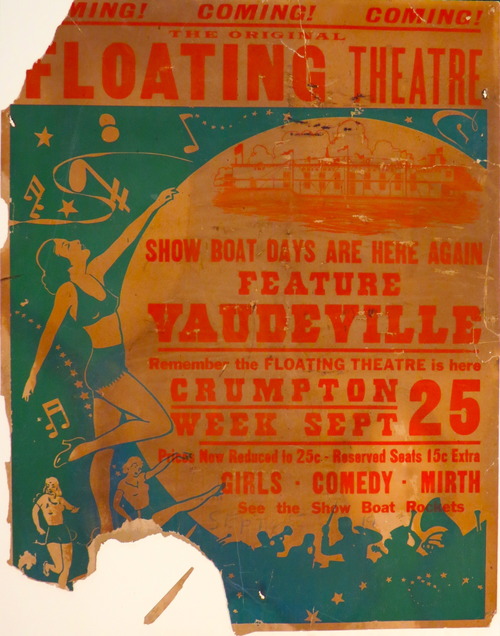

A “herald” for the James Adams Floating Theatre. Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

The posters came first. Screaming with gaudy colors and emblazoned with ladies emerging from a haze of stars and clouds with legs extended in a Jazz-Age salute, the imminent appearance was heralded: “Coming! Coming! Coming! Show Boat Days Are Here Again!"

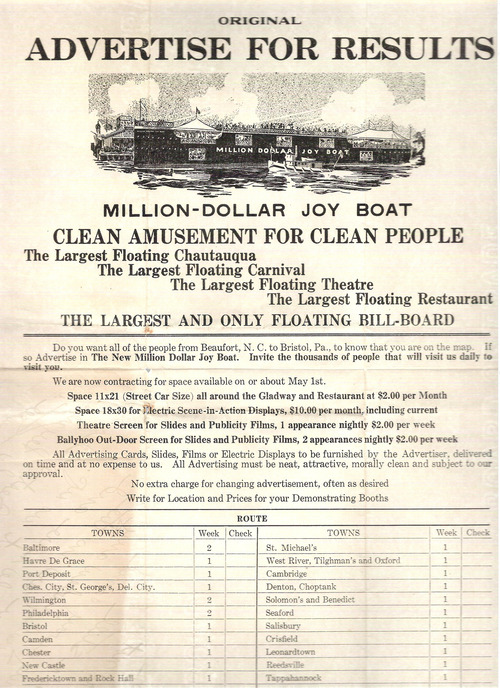

Pasted on the walls of remote river towns in Maryland and Virginia, these visual whoops of excitement shared the news of the James Adams Floating Theater’s hotly anticipated arrival. In the deeply rural and isolated Chesapeake of the early 20th century, tidewater communities like Crumpton, Tappahannock and St Michaels were places where life revolved around seasonal cycles on the water and the land– tomatoes, peaches and crabmeat in summer, oysters, waterfowl and muskrat in winter. For Bay folk tethered to the river, it was a quotidian life, stable but utterly devoid of glamour. From Reedville to Chestertown, Chesapeake communities were starved for an infusion of glittery escapism.

The Floating Theatre. Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

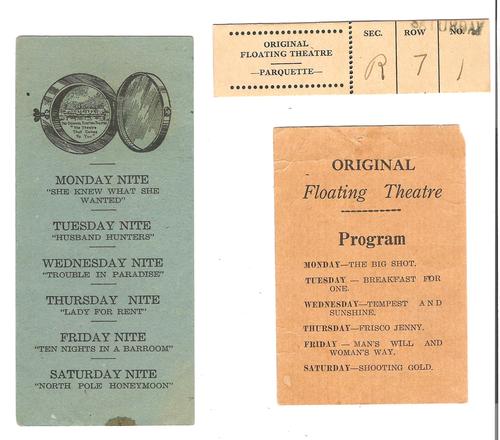

The James Adams Floating Theater’s bulk dockside was a Faberge egg of delights that promised a panacea for humdrum hamlet life: a week of nightly romance, adventure, comedy, and music in the 800-capacity auditorium. As long as they had a water access and a few dimes squirreled away, audiences along Bay tributaries could sigh with the lovelorn ingénue in Tempest and Sunshine, discover ‘whodunnit’ in The Boy Detective, and shout with encouragement as winsome cowboy defeated the magnificently-mustached villain in Sunset Trail. From 1914 to 1941, the James Adams Floating Theater enchanted small towns and cities throughout the Chesapeake’s tributaries. Long after its circuit was abandoned for newfangled talkies and colored pictures, the legacy of the magical little showboat lived on in the memories of its audiences.

The Floating Theater was the brainchild of a seasoned entertainer and vaudevillian, James Adams, who had made his fortune in the travelling carnival business. In the late 19th century, while a retinue of showboats plied their trade throughout the rivers of the Midwest, Adams discovered while working the carnival circuit in the Southeast that the East Coast was still wide open to the opportunity.

A write up on the Floating Theatre from the Baltimore Sun, November 22, 1925. Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

It was a time period when, according to the US census, over 60% of the American population still lived in rural, agricultural communities. But even the humblest of towns often boasted its own theater, an outpost of civilization and culture in remote locales. These small stages, ranging from utilitarian platforms to elaborately appointed entertainment palaces, hosted various troupes of travelling performers during the heyday of the “American Repetoire Theater Movement.” During a peak of popularity that lasted for the first four decades of the 20th century, travelling Repetoire companies, comprised of a corps of versatile actors and musicians, provided the main source of entertainment for small town America. Melodramas, musicals, and romantic comedies were the most popular offerings, followed by farces and minstrel shows. Modern audiences would find the fare low-brow and hammy, but in farm towns and fishing villages, it was an escape from the hard physicality of a world where machines had just begun to make everyday life easier.

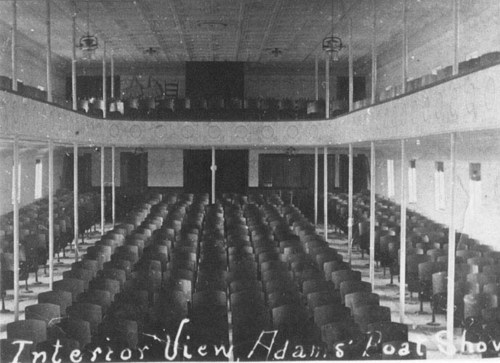

James Adams, a savvy showman, knew well the demand for small-town travelling entertainment, and set about capitalizing on it in 1913 with the construction of a 128-barge in Washington, North Carolina, named Playhouse. Within its 30-by-80 foot auditorium appointed in a cream, blue and gold color scheme, there was room for 500 on the floor and 350 in the balcony, providing the capacity to perform to entire towns. Adams spared no expense- his “Floating Theater” boasted a stage, room for a 10-piece concert band and a 6-piece orchestra, a galley, a dining room, running water, and room for 25 live-aboard cast and crew. The exterior was painted an immaculate white, with dark trim, porches and balconies.

The Floating Theatre’s interior. Image courtesy floatingtheatre.org

Its design, however, was pragmatic as well as pretty- drawing only 14 inches of water when it was empty of audiences meant the Playhouse could easily reach the little towns crowded like barnacles alongside the Chesapeake’s shallow tributaries. Towed by two tugs, Trouper and Elk, on either end and emblazoned with “James Adams Floating Theatre” in lettering 2 feet tall, the theater’s buoyant bulk made its leisurely way to river communities throughout the watershed in the season between April and November.

Once the Floating Theatre appeared dockside, its small-town hosts could anticipate a week of nightly entertainment, from plays and musicales to concerts of the latest popular tunes. Vaudeville bits and specialties performed by actors and musicians in the company added variety and comedic relief to the playbill. While the company was in a state of constant change, with new members being added and subtracted every season, a few regulars cottoned to the nomadic lifestyle of the Playhouse and became featured stars of the theater’s reviews. Beulah Adams, the sister of James, performed trademark roles as the paragon of the blushing ingénue. Known as the “Mary Pickford of the Chesapeake,” with her trademark sausage curls, dimpled smile and petite stature (as well as the help of some artfully-applied stage makeup), she continued performing convincingly as a young girl on the Floating Theatre’s stage until she retired at the age of 46.

An solicitation for advertisers along the route of the Floating Theatre. Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Charles Hunter, Beulah’s husband, was another longtime Floating Theatre troupe member, playing character roles from straight men to love interests. During the vessel’s second season in 1915, he joined the cast, eventually moving up to direct plays and provide artistic oversight. Hunter, although a versatile and competent actor, was dogged by his extremely poor eyesight. To look younger for roles, he’d remove his thick glasses before going onstage, but had to cling to the curtain while entering and exiting and blindly grope his way back to the wings once his act was over.

Pop Neel was another longtime Floating Theatre cast member. A grizzled veteran of the carnival circuit, Neel had played with scores of circus bands until he came aboard the Playhouse in 1914 at the age of 56. A cornet player, Neel played competently until his age and health began to take their toll on his teeth. By the early 30’s, his dental state was as dilapidated as an old picket fence, and in order to have him continue to perform, the Floating Theatre’s management bought him a bass fiddle that he played until his retirement in 1939 at the age of 79.

Locals were encouraged to support the Showboat’s visits, which resulted in some special perks for those willing to pitch in. Young boys were often singled out for minor chores, toting and fetching, in exchange for tickets to that evening’s entertainment. Hartley Bayne, a Crumpton resident in the 1930’s, remembers the thrill of “working” for the Floating Theatre as a ten-year-old: “The actors had their private rooms on the Showboat. They had to have fresh water, water to bathe in. So the boys in Crumpton, and I guess, Centreville and Chestertown, we carried buckets of water up and I would do two different actors’ rooms at a time, so all of them had fresh water. And that night, I’d get in free, because I was a waterboy.”

Bayne later became a pen pal with one of the actors, Thayer Roberts, whom he’d befriended during a visit in 1935. Roberts, a seasoned vaudeville performer, went on after his stint with the Floating Theatre to transition from theater to film and played bit roles in B movies for the rest of his career. Though his life took him far from the sweltering tidewater where he’d trod the boards for small-town audiences, it seems he never quite managed to forget his summers aboard the Floating Theatre. From time to time for the next decade, he’d sit down in his home in the Hollywood hills to write to the scrappy water carrier from Crumpton who would grow up to be my grandfather.

Floating Theatre tickets and playbill. Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Not all audiences were equal, however, for the Floating Theatre. This was the heart of the Jim Crow era in the Chesapeake, when separate-but-equal was anything but, and the showboat was no exception. Anticipating mixed-race audiences, the balcony was originally advertised in 1914 as “reserved for colored people exclusively,” a novel arrangement for the time that galled many conservatives who preferred their entertainment be strictly segregated along racial lines.

Charles Hunter would go on to take his Floating Theatre bits on the road. This playbill from his "Showboat Players” and its inclusion of a minstrel show conveys the sharp disparity between what historical and modern audiences consider to be “entertainment.” Collections of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

However, the attempt to draw more diverse audiences proved to be a failure for the showboat- regardless of their ‘forward-thinking’ separate seating. For African-Americans in the Bay region, many restricted to low-wage menial jobs, the ticket prices were far beyond affordable. James Adams acknowledged this disparity when interviewed for The Saturday Evening Post in 1925 commented to the interviewer, “The 20-35-50 cent scale is a bit beyond the range of the negro population. Most of them… (wait) on the wharf, listen to the music inside, and wait for the 15-cent concert after-show.”

A showboat staffer in the late 20’s and early 30’s, Maisie Comardo, identified another reason that African-Americans avoided the Floating Theatre- curfews. Commardo reflected in an interview years later that many African-Americans did not want to linger in the white part of town as late as the concert ended. Frequently, small Chesapeake towns restricted their main streets after hours for white-only use, with violent repercussions if those restrictions were ignored. For many locations throughout the circuit, that curfew would have started before the showboat’s final curtain call- effectively eliminating any chance of attendance for all people of color in the community.

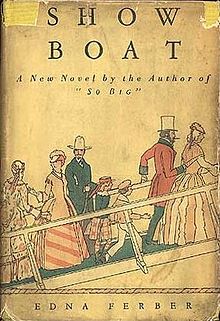

First edition cover of Edna Ferber’s “Showboat.”

The Chesapeake’s racial disparities highlighted by the James Adams Floating Theatre were to become nationally famous when the Playhouse was immortalized in Edna Ferber’s novel, Showboat. Ferber had first visited the Floating Theatre in 1924, while the vessel was in Crumpton, Maryland for a week, and later travelled to North Carolina in the spring of 1925 for a second, longer stay. Through her own observations and interviews with cast on the Floating Theater, especially Charles Hunter, Ferber compiled extensive notes onboard the Playhouse, documenting the culture and community of the little showboat and the isolated tidewater towns it visited. Ferber later described the rich content of her interviews with Charles Hunter, who was a bit of a raconteur once he finally opened up: “Tales of river. Stories of show boat life. Characterizations. Romance. Adventures. River history. Stage superstition. I had a chunk of yellow copy paper in my hand. On this I scribbled without looking down, afraid to glance away for fear of breaking the spell.”

Ferber published Showboat to public acclaim in 1926- it spent 12 weeks on the New York Times Bestseller list, and inspired a blockbuster Broadway musical of the same name in 1927. Although the story was fictionalized with a Mississippi setting and an imaginary cast of characters, the glories of the Floating Theatre’s limelight and the cruelties of the Jim Crow Chesapeake were addressed with arresting realism on Ferber’s Cotton Blossom. Immortalized on the page, the stage, and in 1936, on the big screen, the success of Showboat helped to ensure that the memory (albeit slightly embellished) of the James Adams Floating Theatre might fade from public recollection, but it would never disappear entirely.

The publication of Ferber’s Showboat and the subsequent adaptations that followed marked the acme of the Floating Theatre’s history. As its star set, the movie industry and radio were becoming powerful cultural juggernauts, supplanting Repetoire companies as the small-town choice for entertainment. By the late 1920’s the Floating Theatre was facing hard times. In 1927, she sank near Norfolk Harbor, requiring expensive repairs, and again in 1929, near the Great Dismal Swamp. The Great Depression only continued the downward spiral for the showboat. Entertainment became a luxury for down-on-their-luck audiences who keenly felt the pinch in their pocketbooks.

By 1933, it was the end of an era. James Adams sold the Floating Theatre to a St Michaels woman, Nina B. Howard, who managed the boat with the help of her magnificently-monikered son, Milford Seymoure. Although Beulah Adams and Charles Hunter stayed under the new management, times had changed and business continued to fall off. Audiences throughout the showboat’s circuit were no longer transported by the sentimental romances and slap-stick comedy after experiencing the elaborate sets and subtle, emotional acting of the moving pictures. By 1936, Hunter and Adams finally quit and began a land-based touring company. In 1938, the showboat sank for the third time in the Roanoke River.

Three years later, again under new ownership, the Floating Theatre caught fire in Savannah, Georgia. Her flocked wallpaper, dressing rooms with knotty pine, cramped, oil-splattered galley, and the gold and silver painted seats of her auditorium flickered in the blaze of her final curtain call. It had been a good run. So many dusty Chesapeake towns had drowsed under the Floating Theatre’s spell, roaring with laughter, crying in sympathy, clapping their hands and singing along to “Buffalo Girl” and “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.” Through World War I, the Depression, the great monolithic hulk of the Floating Theatre approaching downriver meant diversion from your troubles, a blissful cocktail of comedy, razzle dazzle, and glittery fantasy.

Although audiences would never again gather each night by the town wharf, ticket in hand, her music and her mugging entertainers would live on in their delighted memories, and in the stories they told to their children and grandchildren. Certainly, my grandfather was no exception. “It was special to be picked, and I went to help every day, so I could go at night,” said my Pop-pop, Hartley Bayne, reminiscing about his water boy days in Crumpton. “It was the best week of the year, and everybody in the whole town was there, at the showboat.”

William “Wit” Garrett recalls taking a date to see a show at the Floating Theatre in his teens:

An effort is being made to recreate the James Adams Floating Theatre. Read more about the project here: http://floatingtheatre.org/

It’s getting to be that time of year- crabbing season opened a few weeks ago, and the first scuttlers should begin swimming up the rivers and emerging from their winter beds in the next month or two.

Photo courtesy Tracey Munson.

A late 19th century shad planking celebrates the first major catch of the spring. Now part of the Chesapeake past, the commercial harvest is closed due to low shad populations, but during its heyday, shad was ubiquitous- cheap, plentiful and delicious. The only downside was the thicket of tiny bones inside. Planking the fish over a slow, hot fire allowed the tiny bones to dissolve in the even heat, and produced a crispy, oily fish perfumed by the hickory it had sizzled on.

Shad plankings were large community gatherings to celebrate the return of spring, and as such, attracted politicians looking to curry favor while bellies were full and spirits high. Today, the term “shad planking” is synonymous with political stumping.

In this 1905 photograph, a burst of dockside activity at Baltimore’s working waterfront harbor has been captured for posterity. Oysters by the bushel-full are unloaded from bugeye to wagon. Unlikely characters for such muddy labor are dressed in bowler hats, ties, and jackets, while dockhands, better attired for the job, hoist their cargo in creased, stained work clothes. The harbor’s surface is fouled with a scum of refuse and slime, a reminder of the fact that Baltimore’s sewer system was built 7 years after this photo was taken. In the foreground, a bowsprit thrusts almost into the camera, while another, with sail furled, crosses below.

A photo is worth a thousand words, but a picture like this, rich with detail down to the oyster shells crushed into the cobblestones, can be better than time travel.

Photo courtesy of shorpy.com

For a high resolution image: http://bit.ly/1hFpJ6G

Blackwater Refuge

The Blackwater National Wildlife refuge looks, from google earth, like the arteries of a great, mossy giant- the low forest and marshes drained and refreshed by thin, branching veins of tidal tributaries. As your eyes adjust, attempting to discern the difference between green canopy and greyish water, you feel disoriented- how can so much water and so little land still make up a destination? So extensive and switchbacked are Blackwater’s myriad tributaries, that within its 27,000 acres is 1/3 of Maryland’s tidal wetlands. This is alpha and omega of Chesapeake marshes- a place where land and water overlap, interconnected and symbiotic.

The guts, coves, and marshes that stitch together the damp high ground reflect the wild, backwoods nature of the place- “Otter Pond,” “Snarepole Gut,” “Wolfpit Pond,” “Hog Rooting Pond.” Blackwater, the names suggest, is not a refuge for humans, but an untamed relic from the Chesapeake’s less civilized past. A walk along the numerous nature trails is an immediate reminder that you are, indeed, the interloper from the tamed modern world. Bleached, rasping marsh grasses barely part above you as your sodden shoes squelch through cake batter mud. Cicadas scream in loblollies and, far above, eagles wheel in funnel shapes, following the warm drafts up, up.

Winter sunset at Blackwater.

The refuge is fed by the tannin-rich water of the Blackwater River and the Little Blackwater, which derive their distinctive tea-colored tint from the ancient peaty soils of the region’s pine woods. Once a haven for Nanticoke Indians and a hiding place for Harriet Tubman and other runaway slaves as they journeyed north to freedom, Blackwater is now a sanctuary for the wildlife that teems within its verdant 25,00 acres of brackish tidal wetlands and evergreen and deciduous forests. Over 250 different species of wildlife are concealed within rustling treetops and the flattened dunes of salt meadow hay: eagles, falcons, hawks and osprey, the meaty silver bulk of the Delmarva Fox squirrel, and in the mud-baked tidal flats, the spiked fur and distinctive tail drag-marks of the omnipresent muskrat.

Where land and water intertwine at Blackwater.

Muskrat tracks at low tide.

Seasonally Blackwater is visited by fluttering flocks of migratory waterfowl in the tens of thousands, which feast on the refuge’s thick underwater grasses and paddle contentedly in its icy shallows. Birdwatchers and photographers are drawn to the spectacle, documenting the mouth-dropping ascendance of snow geese in flickering white drifts, the glossy chestnut plumage of the dapper canvasback, the aloof red-tailed hawk winking across the path of the sun. Countless photographs in galleries, posted on Flickr and Instagram, are visual testimony of the feathered eye candy so brilliantly on display at every Blackwater creek and cove.

Migratory waterfowl overwintering on a Blackwater inlet.

A nest of spring-hatched osprey.

Established in 1933, the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge was created during a period when the enormous flocks of migratory waterfowl that had once visited the Chesapeake along the Atlantic Flyway were recovering from a deep decline, due to overzealous harvesting. Now protected from most forms of market hunting after the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, refuges like Blackwater provided rich habitat for waterfowl while restricting access to the still-legal sport hunting.

Photo by Chris Koontz/Flickr

Today, Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge has been referred to by the Nature Conservancy as the “Everglades of the North” -a protected, jewel-like place that has produced a dynamic, deeply interconnected Chesapeake environment seething with biodiversity. But even as the refuge shelters hundreds of species within in its drowned forests and slow, quiet inlets, it is also threatened by sea level rise and erosion. The Chesapeake Bay reclaims more than 300 acres of Blackwater’s low land each year. Through the efforts of the Conservation Fund, higher land surrounding the refuge has been purchased and added on to the original acreage, creating a cushion for the inevitable slow creep of the water level.

A songbird clings to a reed of marsh grass.

Dissolving into the ever-widening maw of the Bay, Blackwater is a paradise for a protected population of wild things with feathers, fins, and fur. Even as its marsh tumps fade below the waterline, Blackwater’s loblollies are ornamented with heron rookeries, its grasses cloud with insects, and its water churns with spawning fish runs. While the future of Blackwater’s shores might be imperiled, for now, it is still a vibrant sanctuary where life goes on untroubled by the glowering clouds of climate chamge. Push through the wet feet and mosquito bites, and a visit might reward you with glimpses of a untamed Chesapeake past , as elusive and slippery as an otter, darting just below the water’s surface.

A Library of Congress photo with what appears to be a Pungy and a Bugeye (square sterned) or pilot schooner, being repaired on the Potomac River, 1862.

This may be the earliest documented photo of a Chesapeake Bay Pungy. The fact they are being rebuilt on a railway makes them even older.

Sturgeon Creek by jon_beard on Flickr.

Thinking about Chesapeake summers, at the end of a long, cold winter.

This month in maritime history:

For proof that Chesapeake history does not always create an air of nostalgia, one needs to look no further than the devastating Great Fire of 1904- an event that destroyed much of Baltimore’s harbor neighborhoods- and paved the way for the modern Baltimore harbor we know today.

Looking southeast from Continental Trust building

Baltimore, Maryland

February 1904

Unidentified photographer

The Great Baltimore Fire Photograph Collection

PP179.174Full image with detail.

Maryland National Guard, Great Baltimore Fire of 1904

Baltimore, Maryland

February 1904

Unidentified photographer

Subject Vertical File

SVF (Baltimore - Fires & Explosions)Full image and detail.

Burnt District map, The Sun Magazine (detail)

1904

The Great Baltimore Fire Photograph Collection

PP179.727

It’s the 110th Anniversary of The Great Baltimore Fire of 1904.The Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 started on Sunday, February 7, at 10:48 a.m. with a fire alarm sounding the Hurst Building, Liberty Street and Hopkins Place on the south side of German Street (now Redwood Street). The fire would continue until approximately 5 p.m. Monday. The Great Fire was the largest municipal disaster in American history up until that time. The cause of the fire has been speculated as beginning with a discarded cigarette or cigar butt falling through a two-inch hole in a glass deadlight in the sidewalk above the basement of the Hurst Building.

Brisk winter winds spread the fire easily, and suddenly Baltimore’s fire department realized that they would not be able to contain the disaster solely and help from the surrounding area, including Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia, was requested. The fire destroyed 86 blocks and resulted in one direct fatality from the fire and four fatalities from illness attributed to the fire. More than $70 million in property loses were reported.

19th century advertisement for Chesapeake Bay oyster distribution company. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Our Bronza Parks-built draketail, Martha. The prettiest deadrise north of Hooper’s Island.

One of the most gorgeous Chesapeake views is our campus at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in early morning, after a fresh snow. With a frozen harbor and a chilly hush over the town, only the call of the geese, far overhead, is a reminder that it isn’t just a picture.

A 60’s version of the perfect, modern Chesapeake Bay landmark- sitting on one of the richest archaeological sites in the region, and commanding some of the best views in the entire watershed.

Swanning About

Tundra swans on Eastern Neck Island.

Over the frozen Bay a high fluting call echoes off the ice and resonates. It heralds a flying wedge of some of the most magnificent migratory waterfowl to grace the Chesapeake, come wintertime- swans. These arctic natives, all chilly white, populate the coves along the shoreline throughout the Bay’s deepest winter. Along with scores of ducks and geese, swans seek refuge in the Bay’s many rivers, creeks, and marshes, punctuating the icy shallows with their distinctive woodwind calls as they feed on the Bay’s underwater meadows. Once these enormous, powerful birds were the most coveted game a hunter could bag, and swan decoys, poised in repose or bottom-up in full feed, were added to a mixed rig in hopes of attracting an unsuspecting tundra swan.

Swan hunters at Miller’s Island, late 19th century.

Swans were a waterfowler’s prized trophy. Traditionally, swan populations were smaller in number than the other waterfowl, and their ivory feathers and huge wingspan stood out distinctively from the rest of the flock, making them both relatively rare and easy to spot. In that era, when every Chesapeake marsh was crowded with waterfowl in the wintertime, a light dusting of indigenous Tundra or Trumpeter swans was part of the landscape. Their oboe-like calls made them just as identifiable by sound alone.

Swan hunting was effectively ended in 1918 with the Migratory Bird Act, which protected hundreds of species of birds from killing or capture, whether for their flesh or their feathers. It was exoneration for the magnificent migrators, and ensured that countless new generations of swans would continue to wing their way south towards the Chesapeake once the days began to shorten. By 1972, according to the Mid-winter Waterfowl Survey, the Chesapeake wintered more than 70% of the tundra swans in the Atlantic Flyway.

Tundra swan, Kent Island. Photo courtesy of chesapeakebay.net

But since the 1960’s, there’s been a beautiful impostor infiltrating the Chesapeake- the mute swan. As year-round residents, these European swans devour the already-imperiled underwater grasses of the Bay, and addressing the problem of their population boom and its impact has created controversy among Chesapeake residents and landowners, bird lovers, and the Department of Natural Resources.

Mute swan, photo courtesy of chesapeakebay.net

The mute swan, an invasive species, was first introduced to the Chesapeake as an ornamental bird. Native to Europe, these elegant-but-voracious domesticated birds were used as scenery, decorating ponds on private estates. In 1962, five mute swans escaped from an estate in Talbot County, not far from where the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is today. These birds went on to reproduce expansively, and their offspring evidently found the Bay’s grassy bottom and protected shoreline to be a perfect new home. In 1999, their population count hit an all-time high, with 4,000 estimated birds.

But if swans are already native to the Chesapeake Bay, then what’s the harm in adding a few more? The answer- seasonality and territory. Mute swans (distinguishable from their native cousins by their curved necks and orange bills) are year-round residents, while tundra or trumpeter swans are migratory. That means mute swans, constantly grazing, are clearing swaths of bay grasses year-round without pause. In addition, their highly territorial nature causes them to trample the nests of other seabirds, and drive off tundra swans when they arrive in the fall.

Mute swans take flight.

Addressing the problem of the mute swan population stirred up much controversy. Beginning in 2001, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources attempted to limit the mute swan’s population growth by removing and relocating adults, addling eggs before they hatched, and when necessary, by hunting. It was a successful strategy in terms of swan control, but the reduction initiative struck a highly emotional note for many in the watershed, from animal rights activists to ordinary citizens. In a letter to the Washington Post in 2011, an Arlington resident summed up how many felt about the control measures:

“Thousands of mute swans have been cruelly killed by wildlife officials over the past couple of years because the birds consume aquatic plants. Only a few hundred mute swans remain in this region.We must teach our children to live with wildlife — native and non-native. Unnecessary killing of mute swans is not a substitute for the humane and enlightened management that these wonderful animals deserve.”

It is worth noting that while the plight of the mute swan was contentious, population control for other, less majestic species has not been so disputed- the eradication of homely nutria, for example, has caused no real public outcry.

By 2012, fewer than 100 mute swans were counted in the Chesapeake- a major victory for the native tundra swans, which now have abundant stretches of shoreline for shelter and sustenance. It also means that the chances have just gotten much better for that magical moment,when the wind dies down and sound carries far over a wintry Bay, that the woodwind peals of a tundra swans, far overhead, can be heard.