The Thomas Point screwpile lighthouse, off Annapolis, correct down to the privy hanging over the water-is there anything Legos can’t do?

Thomas Point Lighthouse (by rabidnovaracer)

Winter on the Chesapeake Bay, Maryland 1977.

In honor of tonight’s temperatures, which will dip to 9 degrees Fahrenheit, a little photographic reminder that when it comes to a cold Chesapeake, nothing is new.

The Mystery of the Chesapeake Christmas Tradition

Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum shipwrights on Old Point in 2011, after decorating her mast with the annual Christmas Tree.

It’s a lovely little nautical Christmas tradition, with just enough pomp to make it memorable. Every year, our shipwrights dutifully cut, light, and trim a tree, then join together to raise it up the mast of one of our historic wooden boats as part of our annual holiday decorating customs. Here, it’s utterly routine, and the St. Michaels harbor wouldn’t look quite the same without its yearly starburst of colored lights at dusk, hoisted gaily over the dark water. But when did this Maritime Museum tradition begin? The mystery of who started this annual ritual and why is something we’ve never really questioned at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

The boatshop Christmas tree waits to be raised.

Our Assistant Curator of Watercraft, the very salty Rich Scofield, has been carrying on the Christmas tradition for his lengthy tenure at the museum, and has a few guesses as to its St. Michaels beginnings:

“I think it is boat tradition, and certainly I have seen and heard about it on Bay boats. I do not remember when we started it. I think when I worked at Higgins (Boatyard), we put a tree up the gin pole we used to pull and step masts. It was about 30 ft high… and I said it was the tallest tree in St. Michaels.

My brother was working in the (CBMM) boat shop then and I think they decided to top us and put one up our skipjack, Rosie Parks. I came back to the museum in 1985 and was given the job of finding a tree and putting it up Rosie’s mast and I have done it ever since.”

Scofield and other CBMM shipwrights haul the Christmas tree up the mast of the recently-restored skipjack Rosie Parks.

The traditional hoisted-tree is a annual ritual observed outside the museum among a few other Bay watercraft, but the origins of the custom are similarly murky. Is a Christmas tree on the mast a boating thing? A Chesapeake thing? A St. Michaels thing? A little sleuthing turned up only more questions, served up with a couple of great anecdotes.

Nathan of Dorchester, a Cambridge skipjack decorated annually with lights, garlands, wreaths, an angel, and a masted tree by local volunteers and a little help from the local fire company. Image courtesy Nathan of Dorchester.

Captain Wade Murphy, owner and captain of the skipjack Rebecca T. Ruark, has seen a lot of Chesapeake boats in all seasons in his 60-year career. Although the Rebecca is part of the masted Christmas tree tradition and typically boasts a decorated tree from Christmastime until the end of the oystering season, Wade’s not too sure where it started, either. However, he had this theory about the custom, based on the Rebecca’s previous owner, Captain Todd, who raised a tree up the mast, too: “This fella that owned my boat (in the 60’s and 70’s), liked decoration. He thought so much of this boat that he dressed her up, like jewelry on a woman.” The urge to spruce and prettify is not a stretch for a truly devoted sailor (and it certainly can explain the Rebecca’s decorating tradition, if nothing else), but surely lashing a tree to a mast has roots extend further- perhaps even beyond the brackish Bay waterways?

Christmas takes place during the heart of the Chesapeake oystering season.

Some research reveals that there may be an international historic precedent for masting trees in another the tree-raising tradition, called “topping out.” A Northern European ceremony for the completion of a building or boat, the custom called for raising a small decorated tree or branch of greenery on a beam or mast above the finished construction. The practice can be traced back to Scandinavia, where natural features, like streams and trees, were revered as deities in the ancient Norse religion. To honor the tree-dwelling spirits that been sacrificed for the construction of a wooden vessel or structure, a symbolic tree was placed on the top of the new boat or building. The practice migrated throughout Europe with Scandinavian immigrants, and eventually lost its religious connotations, simply becoming a way to commemorate a completed construction or shipbuilding project.

CBMM crab dredger, Old Point, all lit up along the waterfront on St. Michaels harbor.

Whether started by tree-worshipping Vikings or captains with a desire for decor, the tradition of hoisting a little tree blazing with light and color to the top of a tall mast is carried forward at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum every year. It’s a bit homespun, and certainly no equal to the flashing LED’s and singing reindeer boasted by some of the grander homes along the harbor, but our one little tree doesn’t need newfangled conceits to get its message across the still water:

All is calm. All is bright.

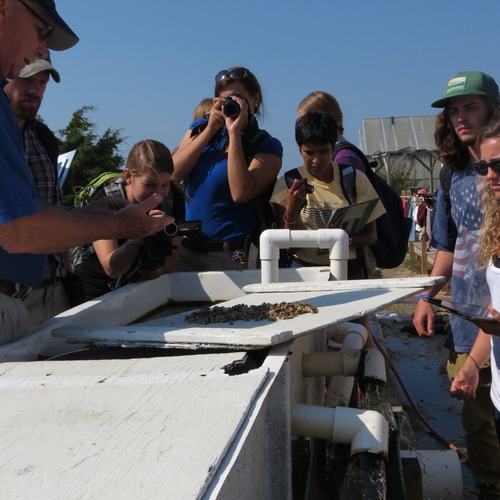

"Growing" Aquaculture at Ballard Oyster and Clam

A salt marsh in Chincoteague, with oysters breaking the water’s surface.

All the way down the long stem of the Eastern Shore of Virginia’s peninsula, a thriving industry exists in the salty marsh inlets and tidal coves. Where the water line breaks, they emerge: oysters. Thick and toothy, their grey backs crest above the surface as the water recedes with the tide. Exposed, these oyster reefs of peerless productivity show their complex structures, and all the hangers-on that survive inside: barnacles, mussels, shrimp, sea squirts, mud crabs, anemones. Oyster catchers, with their bright red bills and rabbit-red eyes, wade through the rubble spearing the finger-nail shells of spat. It all seems utterly untouched, wild, and timeless. But looks can be deceiving. These oysters, so expansively productive, are also intensely cultivated. Down here in Virginia, oyster leasing has been a part of the seafood industry for the last hundred years. After a century of farming, it’s clear even to the casual kayaker- this method has produced oysters so fertile every reed of marsh grass, piling, and submerged stick is covered in clusters of their spat.

Shellfish, especially the farmed variety, is big business down here- according to a recent article in the Washington Post, over two-thirds of Virginia’s current harvest of 405,000 bushels came from aquaculture. Currently, about 100,000 acres of the state water bottom is farmed by aquaculture leases. Clams as well as oysters are produced and shipped throughout the United States, where the terms “Chincoteague” and “Cherrystone” are synonymous with the best salty delicacies the Chesapeake can provide. Especially in the last ten years, this traditional bottom-leasing has been booming, with large-scale farms providing a substantial support to the growth of the oyster economy. On the deeply rural Eastern Shore of Virginia, this expanding aquaculture market may be the only kind of rapid growth many folks can support, if their bumper stickers are anything to go by.

Our guide, Ron Crumb, a longtime Ballard employee, showing off Ballard’s harvest. Photo courtesy of Ballard Oyster and Fish company.

One of the best examples of the humble farmed oyster’s economic power is the Ballard Oyster and Fish Company, largest Eastern Shore producer of aquaculture oysters and clams. The company’s origins can be traced back to 1895, when a member of the Ballard family began working as a waterman. Throughout the early 20th century, the business was primarily run as a wild oystering concern, and the company grew as hundreds of additional leases were purchased. When MSX and Dermo began to impact the oyster population in the 1960’s and 70’s, the owner, Chad Ballard, turned the company’s energies to the stable hard-shell clam market, only reentering the oyster market in the mid-90’s.Today, they have two divisions- oysters and clams, each with several different lines to meet every market demand, and their employee roster includes as many as 120 people in the summertime.

On a recent tour of the Ballard main site in Cheriton, Virginia, we were met by the gregarious Ron Crumb, a longtime Ballard employee and the son of a waterman. He showed us the process of growing clams and oysters, both of which are produced in their on-site nurseries and then grown at multiple Ballard-leased locations offshore once they’re large enough. The tiny hard-shell clams were about the size of peppercorns, and there were millions of them in the outdoor tanks that continuously flushed with seawater.

Along the docks, the oystering side of the business was obvious- a towering pile of oyster cages, scarred with dessicated algae; bins full of spat ready to be moved into flats; a huge quick-sort machine on a barge laden with oysters. Bits of broken shell and crusted mud crunched under our feet. The smell of spent shell and the brine of decay was ripe in the day’s heat. Millions of oysters were transferred to and from the water here, and the evidence was clear to all of your senses.

Bags of baby clams being picked up by a worker in Ballard’s co-op.

Much of Ballard’s clam stock comes from co-operatives, where local watermen will buy the baby clams from Ballard, grow them on their own leases, and then sell back the surviving mature clams at a profit. It’s a method of aquaculture that has meant survival for many watermen in an era when its getting more and more difficult to make it as one-person enterprise, and there are dozens of members in the co-operative taking advantage of the arrangement.

Central to the facility is an immense packing house, where clams are separated by size and bagged, and oysters are packed and readied for wholesale. The first thing you notice is the temperature- it’s right around 40 degrees- perfect for keeping shellfish fresh, but a serious contrast to the 90 degree day outside. In these chilly conditions, dozens of workers guide clams into the sorter, bag them according to size and weight, and in the back, culling hammers help separate individual float-grown oysters from their clusters. There are also several packing houses offsite in Willis Wharf and Chincoteague, where Ballard’s bottom-grown oysters go for shucking and canning. It’s a massive enterprise that takes parts of the oyster and clam industry that were formerly separate and streamlines the process into multiple stages of a single system- Henry Ford would be proud.

The final products– cherrystones as sizeable as paperweights, and oysters whose edges curl like hair ribbons– are shipped via truck and plane to customers throughout the United States, where they impart the flavor of the Chesapeake environment to savvy shellfish connoisseurs. Ballard’s model has proven so successful that they’ve branched into multiple lines of oysters, each differentiated by size, taste, and origin. It would be no exaggeration to state that a consumer could eat a Ballard oyster every night of the week and not enjoy the same variety twice.

Some of Ballard’s different oyster varieties.

While aquaculture may not be the only way to successfully make it in today’s oyster industry, it is a method growing wildly in popularity in Virginia, where the concept of a bottom-raised oyster is a century-old news. Maryland has taken the first real steps to welcome aquaculture into its primarily wild-caught oyster industry, but in the last two years alone, multiple small companies have been founded by individual growers. It marks a change in tradition, technique, and culture, and there is no doubt that the inclusion of farmed shellfish in a primarily wild Chesapeake market will involve anxiety and an undertone of panic. But if Ballard is any indication, there is room for companies of this approach and scale in the Bay without the exclusion of the waterman’s trade- and if the co-operative example shows, perhaps to its benefit.

A future with more oysters in the Bay, a stronger oyster economy, and more fat, half-shelled beauties to enjoy is exemplified by Ballard Oyster and Clam’s present approach, a model for successful Chesapeake aquaculture.

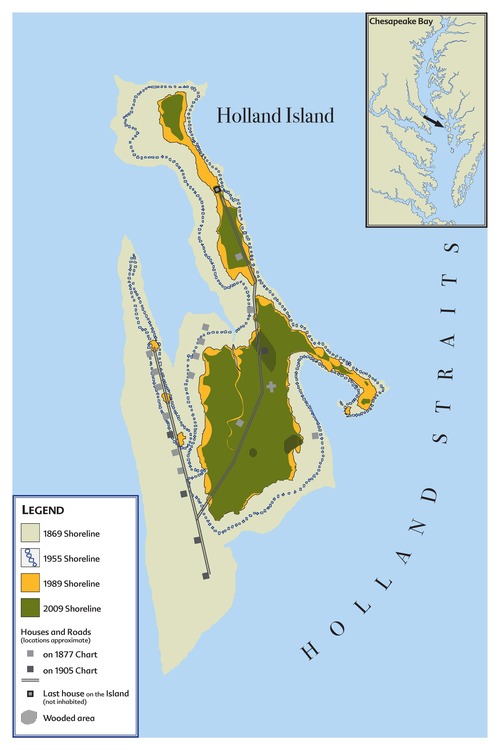

Holland Island, Against the Tide

Once upon a time, there was a small marshy island in the Chesapeake. A fragment in a spinal strand of islands stretching from Bloodsworth to Tangier, Holland Island had a thriving community whose vitality reflected the richness of the Bay’s cornucopia. Finfish and crabs, oysters and turtles were harvested in their seasons by the residents of Holland Island, who numbered 360 souls by the beginning of the 20th century. Over the years, they established community hubs around which the wheels of island life turned: a church fringed by bay grasses, a two-room school, stores, a post office. Island afternoons in summer were peppered with the crack of baseball against bat at the island’s own white-limed diamond.

19th century image of Holland Island houses, located on the island’s highest ridge.

Holland Island’s church, school, and hall from a late 19th century photograph.

Holland Island’s mainstay was referred to as the “water business”, and a prodigious fleet of flat-white-painted workboats connected the islanders to the ballooning seafood industry in Baltimore, Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia. These were the island’s years of milk and honey. The tidily-prosperous Victorian houses that marched down the island’s backbone were a testament to the Chesapeake’s vast productivity in what would be later recognized as the “Golden Era” of Bay harvests.

Holland’s Island watermen checking their pound nets in the 19th century.

But Holland Island’s boom years were soon to turn with the tide, quite literally. Because every wave that kissed the islands shoreline also washed it away, at first imperceptibly, but with increasing speed and impact as the years went on. The slender ribbon of land that comprised the island, 1.5 miles in all, began to break up into smaller pieces as the Chesapeake encroached. The little community was now menaced by the same natural forces that had ensured its early prosperity.

The map above shows the erosion of Holland Island over the course of 140 years. Once it was made up of 3 peninsulas which would become fragmented as the waterline reached further onto the land. Houses once located hundred of yards from the Bay became waterfront properties over the course of 100 years. A tropical storm in 1918 that severely damaged the church was the killing blow for the morale of Holland Island’s families. With few other options, the island’s residents began to relocate, dismantling their fine homes and rebuilding them in Crisfield, a town 8 miles away on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. They left behind foundations, bottles, buttons, and other miscellaneous detritus of everyday life. They also left behind their dead.

Photo courtesy of David Harp, http://www.chesapeakephotos.com

Aerial photo of Holland Island, 2011. Photo courtesy of David Harp, http://www.chesapeakephotos.com

For years, only one house remained on the island, which was eventually purchased by a former watermen and minister, Stephen White, who had visited Holland Island as a child. In interviews, he proclaimed his plans to rebuild the island, stating, “It’s a matter of will and ability. I have those, but I don’t have the funds.” For years, he lead a one-man crusade to stop the erosion of the now-depopulated island, traveling from Crisfield by motorboat each day to continue his efforts and forming a nonprofit tasked with saving Holland Island. He applied fruitlessly for state grants to reinforce the island’s shorelines, but the island was privately owned. So, with sandbags, rocks, and an old backhoe he toiled, one man against the tide.

Photo courtesy of David Harp, http://www.chesapeakephotos.com

For years, only one house remained, its toehold on the island’s extreme perimeter perilously shrinking with each rainy season. Well known to sailors, the Holland Island house became a visual touchstone for travelers passing through the island chain to the main stem of the Bay. Seabirds of all description were often lined up on the roof peak, a clamorous audience to the island’s final act. In mid-October 2010, the old Victorian house, peeling and hogged as a scuttled skipjack, finally crumbled into the Chesapeake that had so long labored to claim it.

Today, birds rule the island’s marshy acreage, safe in the knowledge that not a single predator lurks in the spartina. Each tide brings ghosts back of the families and community that once existed here: salt-stained porch trim in a whimsical pattern, a frosted green bottle for digestive tonic, the outlines of the last foundations and headstones, parting the verdant grasses before they, too, are finally submerged.

Jamestown's Skeletons

Reenactment from the Jamestown 400 Anniversary Celebration

Jamestown, as the birthplace of (successful) European colonization in the Chesapeake, is the focus of much historical romanticism, locally and nationally. A few years ago, in 2008, there was a 400th anniversary commemoration of Jamestown’s settlement that clearly represented how the little colony continues to capture our country’s imagination. The celebration, held at the location of the original fort, was attended by the Queen of England, Miss Virginia, representatives from Chesapeake Indian tribes, sweaty people in replica period clothing and lots of American flags. Much ado was made, and there were many uplifting speeches about the bravery of Captain John Smith and the other colonists who persevered in the face of dwindling supplies, a long, hard winter, and the constant threat of death in the savage, untamed wilderness.

Jamestown reenactors recreate the colony’s early days, before sickness, starvation and conflict decimated their population.

Often repeated, too were Smith’s own quotes about the Chesapeake bounty from his accounts of the colony’s founding days, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England & The Summer Isles. In it, Smith described the Bay in effusive terms: “Heaven & earth never agreed better to frame a place for man’s habitation; were it fully manured and inhabited by industrious people. Here are mountaines, hil[l]s, plaines, valleyes, rivers, and brookes, all running most pleasantly into a faire Bay, compassed but for the mouth, with fruitfull and delightsome land.”

It hardly seems possible, given the lofty hyperbole of modern orators and period explorers, that Jamestown’s origin story could hide a considerably darker side- at least, not one that was a foil for ultimate triumph. But recent archaeological discoveries have confirmed the brutal realities of life in the “Fruitfull and delightsome land” and revealed the banal regularity with which Jamestown settlers succumbed to starvation, disease, chaos, and even cannibalism.

A map of “Jamestown Fort” as drawn by the Spanish Ambassador to London, Pedro de Zuniga, in 1608.

From 1607 through 1609, the Jamestown colony had a failure to thrive, despite the arrival of several vessels full of physical reinforcements and additional supplies.These were not the stout pioneers of the 19th century, after all. These were artisans and farmers, lords, bricklayers, and musicians, hardly equipped by their previous life experiences to live off a deeply foreign land.The pressure was on the Jamestown settlers, ill-equipped as they were, to make the community a financial success for their investors at the Virginia Company of London. John Smith wrote to the backers, imploring them: “When you send againe I entreat you rather send but thirty Carpenters, husbandmen, gardiners, fishermen, blacksmiths, masons and diggers up of trees, roots, well provided; than a thousand of such as wee have: for except wee be able both to lodge them and feed them, the most will consume with want of necessaries before they can be made good for anything.”

Smith knew from experience. Under his leadership, the colony had only just managed to eke out a meager survival during the winter of 1608, foraging off oyster bars and a few remaining rations. Self-sufficiency was a goal that seemed far from achievable. But conditions were about to become markedly worse. After Smith was forced to return to England following an explosives accident, the colony was lead by George Percy, whose bungling attempts to negotiate with the regional Indians had incited hostilities and brought tensions to a head, effectively severing much-needed trade parlay for corn and other foodstuffs. As the fall’s seasonal malaria epidemic swept through the camps, the few settlers who survived were hardly able to lay by any provisions for the oncoming winter.

It was a recipe for mayhem and disaster. As the freeze locked down in earnest, the desperate colonists who managed to survive the malarial plague proceeded to eat the leather from their shoes, the starch from their Elizabethan ruffs, and finally, rats and mice. It was hardly a leap from there to the previously unthinkable- cannibalism. Ironically, the settlers had greatly feared the rumors of a savage, flesh-eating race inhabiting the Caribbean islands during their voyage to the Chesapeake- but the savages turned out to be much closer to home. “Now” Percy later wrote, “famine (began) to look pale in ghastly in every face that nothing was spared to maintain life and do those things which seem incredible.”

There have been written accounts of the cannibalism at Jamestown during what came to be referred to as “the Starving Time.” In his book, Love and Hate in Jamestown, author David Price describes the most famous example:

“A man by the name of Collins…cast a hungry stare at his pregnant wife and murdered her in her sleep. He then chopped apart her remains, salted them, and feasted on them. He stopped short of consuming his own child… When Collins’ depravity was discovered, Percy had him hung by his thumbs with weights on his feet until he confessed.” This was not, unfortunately, an isolated incident.

The reconstructed face of the cannibalized Jamestown girl. Photo courtesy of Smithsonian.

While written accounts have described the cannibalism, there had never been any hard proof. But recent archaeological discoveries by Preservation Virginia and the Smithsonian’s physical anthropologist, Doug Owlsley, have finally found evidence: a skeleton and skull of a 14-year-old girl, with cut marks showing that her brain and flesh were removed. Her remains were later discarded in a dump containing horse and dog bones and then forgotten for 400 years, until excavated by the archaeological team.

Cut marks on the skull and skeleton of the remains were clear testimony to the desperate, unhinged acts that had taken place shortly after she died. Her brain, cheeks and tongue had been consumed. It’s a horrifying end for a voyage that started in England, thousands of miles away, and lead a young girl to a land that would soon take her young life.

This grisly story is quite different from the the heroic speeches retold at Jamestown’s anniversary and the romantic legends attached to Pochahontas. But it’s one that makes the colony’s dogged survival all that more remarkable. While not the stuff of speeches, Jamestown’s skeletons have their own history to share, written in bone and waiting to be discovered. They remind us that for every success lauded in America’s history, there were millions of unnamed, uncounted victims that fell, fodder in the quest for obtaining European land in an untamed Chesapeake Bay.

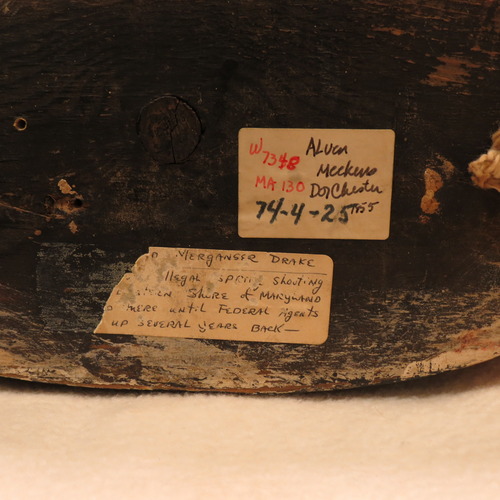

Cool Things from Collections- the Poacher's Decoy

Just a few of our 10,000 treasures in our Collections Building at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

One of the most magical places here on our campus at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is the Collections Building. Tidily arranged on sterile-looking white shelves are a pirate’s horde of Chesapeake treasure: ship models and oyster cans, one-of-a-kind Bay boats from over 100 years ago, sail maker’s benches, steamboat menus, cork life jackets, the first Evinrude outboard motors, antique eel pots, and that’s just on the first row. Each object tells the story of some aspect of Chesapeake life or work, a talisman of a past Bay where the water represented sustenance, stability, and income.

A red-breasted merganser drake decoy, by Alvin Meekins, 1955. CBMM Collections.

Some of the the most interesting things in our collection are the most unexpected. As a maritime museum in the middle of the Atlantic Flyway, it makes sense that our collections would include decoys, as waterfowling is a big part of the Chesapeake’s unique heritage. Generally these are grimy, battered working decoys used for sport hunting, but there are a few decorative ones as well by big names like the Ward Brothers. Within that comprehensive collection of decoys there are a few surprises- like the merganser pictured above. These are working decoys, too, but these are special- created for use in the off season, or for birds that were illegal to shoot. They are examples of poacher’s decoys.

The bottom of the merganser, with a torn detail label.

This merganser drake decoy, made by Alvin Meekins of Hooper’s Island, Maryland, was confiscated at an illegal spring shoot in Dorchester County in the 1950’s, and both the decoy and its use are full of information about the Chesapeake’s environmental history. It was created during a ‘golden era’ of Chesapeake decoy carving, after the Migratory Bird Act of 1918 created limited seasons and shooting methods for waterfowl hunting.

Prior to that time period, there were very few limits to hunting at all, and those regulations that did exist were a patchwork of different limits, seasons, and rules that changed depending on which Chesapeake county you hunted in. Birds could also be baited, trapped, and shot on the water. There was no great need for decoys, which are primarily used in on-the-wing sport shooting.

With the new regulations in 1918, restrictions were federally placed on hunting, regulating seasons, limits, techniques, and locations. On-the-water shooting was eliminated, which suddenly made concealment and camouflage a necessity for anyone who hoped to get a shot at a bird in flight- and opened wide the market for decoys as key element of a waterfowler’s “gunning rig”.

Red-breasted Merganser detail- note the crest.

Decoys varied from river to river, reflecting the migratory birds that sought refuge in different parts of the Chesapeake. The northern Bay, the celery-grass-rich Susquehanna Flats in particular, were famous for canvasbacks, while the southern Bay was the winter home for a large variety of diving ducks.

Dorchester County, Maryland, where the merganser decoy was created, historically offered migrating waterfowl shelter in its expanses of salt water marshland and its reedy shallows, which teemed with small finfish. The mergansers, along with other fish-eating diving ducks, congregated by the millions in these open southern Bay tributaries.

But the drawback with mergansers is that they are what they eat- though filling, their flesh reeks of fish. This was no deterrent for the highly practical waterfowlers in Dorchester County, however, who merely piled the fishy duck on top of the muskrat and woodpecker that already filled their plate and had at it.

Similarly undeterred was the poacher who used this decoy for a spring shoot, several months outside of the winter hunting season. For many years after the waterfowling regulations went into practice, wardens had their hands full and their ears pricked for the sound of gunshots as they attempted to control the waterfowler’s longing to return to the limitless good ol’ days.

Delbert “Cigar” Daisey recalled poaching mergansers and avoiding wardens, “The bulk of the money I made back then was from trapping ducks. You just had to worry about the wardens. Hell, they knew all your traps and who you were selling to. I’d shoot mergansers, sometimes twenty-five to thirty-five a day from February to April, and then sell them to the people who worked in the oyster shucking houses. The good birds, black ducks and pintails, I’d sell to the other professional people during the week.”

As creative as poachers could be in attempting to skirt the law using decoys, baits, traps, or big guns(their backfiring homemade guns were truly works of eyebrow-scorching art), wardens were just as artful at catching them, as our out-of-season merganser proves. Wardens used boats, airplanes, dogs, and ingenuity to catch poachers, and our collections and exhibits have proof of their success, in decoy, gun, and photograph form.

It’s a lot of history in just one decoy, and its just one decoy in a row of hundreds in the CBMM collections, packed carefully away until their story gets a chance to be shared.

Disaster on the City of Baltimore

City of Baltimore as she looked in the early 20th century. CBMM archives.

In the most recent edition of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum’s magazine, The Chesapeake Log, I wrote a story about a disastrous fire onboard a steamboat on July 29th, 1930. The ship, City of Baltimore, was a luxury vessel in the Chesapeake Steamship Company’s fleet, and had 40 passengers onboard blithely enjoying one of the line’s sumptuous repasts in the forward dining room as the steamer left the Patapsco bound for Norfolk. It was a fine night and as the ship steamed past Seven Foot Knoll lighthouse out of the Patapsco into the Bay’s main stem, a light breeze and clear skies held not a hint of foreboding.

The brochure for the Chesapeake Steamship Company advertising their “floating hotels of the most modern type.” CBMM archives.

Around 7:30 PM, a steward noticed smoke snaking up from the hold and set off the fire alarms. Fires onboard steam boats in this period were fairly common and some fire safety was in place- for suppression and for evacuation. The crew immediately responded to the alarms as they had been trained to do by reporting to fire stations, but when they began to unfurl the water hoses, they found to their horror the hoses were dry. The passengers, some still with napkins tucked into their collars, were moved to the fore and aft decks, farthest from the blaze, as the captain and crew tried desperately to quell the fire. It was a busy night on the Chesapeake, with many recreational sailboats and steamers about, and as the situation worsened, vessels began to come to the aid of City of Baltimore as horrified onlookers watched from the shoreline.

Images from the Baltimore Sun show the throngs of shoreline onlookers watching the blaze. CBMM archives.

Without any fire suppression, the flames soon created a holocaust of smoke and light visible for miles around. The captain and crew were running out of options. Captain Brooks attempted to beach the vessel, grinding to a halt on a sandbar before it could reach land. A following steamboat, Arkansan, attempted to come alongside the distressed vessel to rescue passengers and crew, but her forward momentum was so powerful she glanced ineffectually off the side of the City of Baltimore’s hull with a screech of steel-on-steel before retreating. Meanwhile, the metal of the ship’s railings and hull was heating up with the conflagration, and passengers were becoming increasingly desperate to escape. Skin was blistering and summer clothes were scorching in the relentless heat. As other vessels approached to rescue passengers, people began to leap overboard, encouraged by a brave young woman and her setter, Judy, who together made the first plunge off the reddening deck.

The City of Baltimore’s contorted hulk and salvage crews on the morning following the disaster. CBMM archives.

Eventually, all but 4 of the passengers and crew were able to escape the City of Baltimore, picked up by pilot boats and passing sailboats. The vessel was left to burn unfettered, and the hungry flames tore their way through the elegantly appointed staterooms, the dancing salons, the opulent galleries with their chandeliers and fine carved molding, blackening the sky with the char from the finest steamboat money could buy. Though burning of the City of Baltimore would ultimately prove to be a catalyst for the United States to create and implement legislation to improve fire safety on ships throughout the country, it cost 4 lives and the very public destruction of the steamboat in front of a crowds of thousands. Due to the visibility of her demise, The City of Baltimore’s legacy would live on in the stories and photographs that shared the devastation witnessed by so many local Chesapeake families that night.

Horace Plummer’s aerial shot of the City of Baltimore wreckage. Photo courtesy of Bob Plummer.

Horace Plummer was one of those people. Upon the publication of this article, the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum received an email from a man, Bob Plummer, whose father, Horace, had explored the wreck and photographed it the next day by airplane. He had a couple photographs and an artifact, if we were interested. And what treasures they are! In Bob’s pictures, the smoke from the husk of blackened steel hangs in the sky. Several salvage boats are pulled alongside, with Bob’s father, Horace, soon joining them. He found one item to save, a capstan cap inscribed with the ship’s name and its birthplace, Sparrows Point, which remained in his sister’s kitchen in Saluda, Virginia, for over 76 years.

Capstan cap salvaged from the City of Baltimore. Courtesy of Bob Plummer.

It’s a reminder of how much of the past is still in our present, here in the Chesapeake, and how many people and vessels have been lost below the Bay’s placid surface. It’s also a reminder of the power of objects and how much history and emotion can be contained by these tangible relics of the people, places, and vessels that knew the Chesapeake Bay long before we did.

To read the full article on the City of Baltimore, check out an online version of CBMM’s Chesapeake Log here: http://www.cbmm.org/ab_communications.htm

Beauty Under the Old Bay

Nothing says summertime in Maryland like a steaming pile of crabs piled hot and high on a newspapered picnic table, ringed by cold National Bohemians and a throng of hungry people impatient to pick. It’s a slow process, meant for whiling away the long, humid July afternoons with friends and family. Hands around the table are busy prising the white lumps of flesh from their thin crab compartments and mouths are full with the delicate taste of fresh crab meat alternating with the peppery bite of Old Bay. Wash it all down with sips of beer or lemonade, sigh, and start all over again. It might take a few hours to tackle the pile, and even by the end, you might not be full. It doesn’t matter, though- satiation is not really the point, it’s all about the process, the savoring, and the conviviality of a summer gathering. Crabs are a symbol of the best Maryland tradition that represents so much about what’s great and unique about life here; a slower pace, seasonally working the water, and a close connection between the brackish tide and the dinner table. All these things are embodied in those gorgeously red and viciously clawed apples of the Chesapeake Bay’s bottom.

The translated Latin name for the Chesapeake Blue crab, callinectes sapidus, hints at some of the other, more subtle characteristics symbolized by our native sideways swimmer: “Beautiful Swimmer That Tastes Good.” There, right in the name, is the first, obvious thing we all immediately recognize- that crabs are food. Good, tasty food. The food most commonly asked for by visitors to Maryland, summertime or no. But the ‘beautiful swimmer’ can seem like a bit of a misnomer until you poke around under the Old Bay. There’s a lot more to crabs, the process that got them to your picnic table, and the customs surrounding how we enjoy them, than most of us ever consider or imagine. Crabs are a symbol of pleasant living, sure, but they are also a modern-day survivor of much older Chesapeake traditions, history, and the Bay environment of the past.

First off, take a closer look at a live blue crab sometime if you want to observe an animal whose form directly reflects the Chesapeake environment. Sure, the red cooked carapace is pretty (and rings a Pavlovian hunger pang in most of us), but that rich, vibrant blue of the claws, the Bay-toned camouflage of the top shell, and the glistening white of the underbelly are some sort of tidewater firework. Color- coded to be invisible from the top, and pearly white where they touch the Chesapeake’s sandy bottom, the blue-green kaleidoscope of their tinted shell perfectly lends to the crab’s Bay habitat. The construction of a blue crab’s form is another example of their beautifully-evolved functionality. Powerful front claws defend, menace, and form a sort of directional tiller, while the powerful backfins propel the crabs tirelessly from the mouth of the Chesapeake, where they start their lives as zooplankton, to the shallow grassy river bottoms that serve as their sparking spots and marriage beds.

‘Beautifully evolved’ also describes the relationship watermen have developed over centuries of working with crabs, observing their life cycles, their eating and mating habits, watching them scoot off in the water when they see a shadow, or how they’re drawn in by the smell of a mature male or female of their ilk. Watermen have refined their technique by noting even the smallest physical changes that indicate a window for maximum profit. Looking for ‘the sign’ is a classic technique, wherein a waterman looks for an impossibly thin red line on a crab’s backfin that shows up when a crab is about to near the end of its molting cycle. This “sign” also indicates that hard crab, worth maybe $1 to $2 retail, is about to transform into a soft crab, doubling their value to $3 to $5 dollars. It’s a bright red little hairline of pure profit to a waterman who knows where to look, and it reflects generations of working summer after summer surrounded by growing bushels of grabbing, waving, scrabbling crabs.

The techniques surrounding the crab harvest can be things of beauty, but so are too some of the traditions developed around how we enjoy eating them. In particular, adding flavoring to a pot of crabs while steaming is an old custom- older even than the widespread trend of crabs as ‘the’ go-to Maryland seafood, which started in the early 20th century as the availability and prevalence of the oyster market declined. Beer and cider, for example, are a frequent addition to the water for steaming, a foodways holdover from the 18th and 19th centuries. No batch of Chesapeake blue crabs are complete without the classic Old Bay spice mix generously frosted over the whole lot while in the pot, so that it comes off the red shell in thick sheets as the biggest crabs are unearthed from the mound on the table. Named after the “Old Bay” steamboat line, Old Bay was trademarked in the 1940’s by Gustav Brunn, a German immigrant from Baltimore. At the time, crabs were so plentiful and ubiquitous that bars frequently offered them to patrons for free, and salty, spicy seasonings like Old Bay were served on crabs as a means of encouraging the customers to buy more beers.

The tradition of using spices to add ‘heat’ to your crabs goes back even further than the 1940’s, however, and one particular flavoring, fish peppers, can even be traced to a specific Bay location and culture. Fish peppers bear a striped fruit that pack quite a wallop of heat. Developed by Chesapeake African Americans in the Washington D.C. area in the 19th century, fish peppers were used primarily as a spice for seafood- and when crabs went into the cookpot in homes along the Potomac during the 1800’s, a fistful of these vengeful little peppers got tossed in as well. Over time, this piquant and delicious custom transcended cultural lines and was adopted throughout the Chesapeake. Old Bay and other fiery crab seasonings reflect the blistering influence of the fish pepper, and today is one of the reasons we prefer our crabs to not just be served hot, but to taste hot, as well.

Crabs are not just a food in the Chesapeake Bay, but the conveyance of a venerable series of traditions that underscore the fundamental place that seafood and the Bay itself have in our identity, our culture, and our stomachs. So, the next time you turn over your basket of piping hot crabs on a picnic table, dislodge the biggest and fattest, and aim that claw meat dusted with Old Bay towards your eager mouth, think for a moment about the icon that is the Chesapeake Blue crab. Perfectly constructed to swim from the ocean to a river near you, plucked from its eelgrass habitat by a watermen who knows just how it’s done, cooked up in a brine that our colonial predecessors might have enjoyed, and sprinkled with an intense peppery seasoning influenced by the foodways of slaves, the ‘beautiful swimmer’ truly reflects the legacy of the Chesapeake and its people.

This article by CBMM director of education Kate Livie ran in the Chesapeake Log in June, 2012.

The Littlest 1812

In conjunction with our new exhibit “Navigating Freedom: The War of 1812 in the Chesapeake" at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, our volunteer Model Guild worked like feverish Keebler elves on a special diorama to put on display. The idea was to depict a St Michaels shipyard as it would have looked during the conflict, with a ship in progress on the rails and the scores of craftsmen and workers necessary to complete the enormous task.

This busy scene would represent the frenzy of privateer-outfitting that exploded on the Eastern Shore of Maryland after Congress passed an 1812 act giving private ships the right to attack and seize enemy vessels. Legal piracy had a huge appeal and the Chesapeake was at the center of it, turning out nimble clipper ships that sailed at lighting speed and could outrun and outmaneuver their foes- the Chausseur (the later Pride of Baltimore) being a key example.

So enjoy these small-scale snippets of Chesapeake life, 300 years ago, when the Bay was the producer of some of the fastest and deadliest ships the world had ever seen. It’s a step into the life of a St Michaels shipwright in Lilliputian scale with all details intact- right down to the shipyard’s privy.

The shipyard’s rails, outbuildings, and wharves.

Timber arrives, to be shaped into the ship’s planks and frames.

The framing continues, with frame pieces being hoisted into place.

The boiler for shaping the planks.

The master shipwright oversees the construction.

Workers on the scaffolding.

Hoisting the mast with a horse-drawn capstan.

Shipwrights working on the rudder hinges.

The blacksmith’s shop.

War of 1812 boat builders- they’re just like us!

Want to see our new exhibit “Navigating Freedom: War of 1812 on the Chesapeake" for yourself, check out information and visiting hour here on our website: CBMM’s War of 1812 Special Exhibit

The Lloyd's Place

The Eastern Shore of Maryland is a place that feels intensely and seductively timeless. As you move away from the clutter of Kent Island’s Route 50 corridor, the land opens up expansively into vistas that haven’t changed much since the colonial era: wide fields criss-crossed by tough osage hedgerows, dropping their yellow, brain-like fruits into the corn below. Small river towns of peeling clapboard houses with front porches sagging hunker in the humidity, their only concession to the passage of time marked by the direct tv dishes that bristle on their roofs. By and large however, this feeling of the past-as-present is an illusion- modernity has touched every part of this rural landscape. DSL and 24-hour Taco Bells and any store with a “Wal” in its name sidle incongruously with 18th century farmhouses and drug stores where they still make sodas by hand.

Corn crib at Wye House, Library of Congress.

Which is why the true time capsules are all that more rare and remarkable. Wye House in Talbot County is one of these places- a refuge of an elite past Chesapeake, largely untouched and so much richer because of its stasis. Owned by the same family for over 360 years, Wye House is the insect in amber of the Eastern Shore ruling class in its heyday: luminously beautiful from a distance, but with a dark center composed of human sweat, blood and flesh.

Wye House’s long approaching drive and formal facade. source

As you drive to Wye House, each turn down wooded and corn-field-fringed farm lanes seems to husk away another layer of time until your tires on dog-day asphalt could be wagon wheels clattering over dust. The giant oaks and cedars cast deep shadows, almost meeting overhead as you pass beneath, just another of the millions of people who have traveled this way since the Lloyds put down their roots here in the 1650’s.

At the vanishing point of the looped gravel drive, the manor house spreads wide, pillared and hyphened in elegant Palladian rigidity. Around it are gathered tidy outbuildings and barns like chicks flocking to a yellow brood hen. It is prosperous and peaceful, it is seductively old- in short, it is everything we like our history to be: clean, affluent, and seemingly innocuous. But this too is an illusion. It is a monument to the Lloyd’s that owned it, certainly, but just as importantly it is a testament to the slaves that built, maintained, staffed and and farmed it. Like all American history, there are many facets to the past of Wye House and the Eastern Shore property it dominates, and not all of them are appealing.

To this day, a Lloyd family descendant owns the property, which has been handed down, generation after generation, breaking away from its original, vast 20,000 acreage to its current (and still considerable) 1,300 acres today. Land patents of this immense size were not unheard of in the 17th century Chesapeake. It was an era when tobacco cultivation was the economic lifeblood of the region and most farms had huge fallow tracts in states of recuperation from the nutrient-leeching tobacco crop. Tobacco not only needed rich soil to sap, but many human hands to tend- and the Lloyd family, of great influence and puritanical religious leanings, had plenty of ready capital to equip their immense estate with the slaves needed to tend the “16-month crop”.

Names of slaves from an 1805 century ledger kept at Wye House. source

By the turn of the 18th century, the plantation was centered around the grand manor house that remains today, with scores of specialized outbuildings and expensive follies, huge fields and orchards and gardens, fleets of schooners, all staffed, maintained and serviced by 700 slaves. In the 1820’s Frederick Douglass was among them, owned by Aaron Anthony, chief overseer of the Lloyd farms. Douglass lived in one of these dependencies called “the Captain’s House” with Anthony and his family, and was part of the daily life that centered around Wye House, its slaves, and its inhabitants. He later wrote in My Bondage and My Freedom:

“Just such a secluded, dark, and out-of-the-way place, is the "home plantation” of Colonel Edward Lloyd…it is far away from all the great thoroughfares, and proximate to no town or village. There is neither schoolhouse nor townhouse in its neighborhood, for there are no children to go to school, the children and grandchildren of Colonel Lloyd were taught by…a private tutor…The overseers children go off somewhere to school; they bring no influence from abroad to embarrass the natural slave system of the place…Its blacksmiths, wheelwrights, shoemakers, weavers, and coopers, are slaves.“

Exterior and Interior of the Captain’s House, Wye House Farm, from the 1930’s survey of historic American buildings, source

Douglass found Wye House to be the location of some of the most formative experiences in his young life: the place where he witnessed whippings, starvation, and brutality by overseers, and escape attempts by Wye House slaves to North and freedom. He was chosen to be the companion to the young master of Wye House, too, and was introduced to white men of power and influence, inspiring Douglass to ultimately question his place in Wye House, in society, and the existence of slavery itself.

The Orangery at Wye House- a rare,18th century greenhouse, heated by wood fire and a system of hypocausts that supplied Wye House with citrus fruits and hothouse flowers year round.

About the house itself Douglass wrote:

"There stood the grandest building my eyes had then ever beheld, called, by every one on the plantation, the "Great House”. This was occupied by Colonel Lloyd and his family. The occupied it; I enjoyed it. The great house itself was a large white wooden building with wings on thee sides of it…The great house was surrounded by…kitchens, wash-houses, dairies, summer-house, greenhouses, hen-houses, turkey-houses and arbors, of many sizes, all neatly painted and altogether interspersed with grand old trees… that imparted to the scene a high degree of stately beauty… These all belonged to me, as well as to Colonel Edward Lloyd, and for a time I greatly enjoyed them.“

A map by Henry Chandlee Forman of the Long Green at Wye House, location of the outbuildings and activity referred to by Douglass in his autobiography. Source

As in Frederick Douglass’ accounts of Wye House, it remains today a very beautiful, yet very dark reminder of a terrible time in our collective Chesapeake past. The current Lloyd family descendants who own Wye House understand this, and the value the property holds today as a rich repository of physical information that can deepen our understanding of slavery, history, and the foundations of Chesapeake culture. The estate, with their permission, has been the site of ongoing and intensive archaeological digs through the University of Maryland and other partners to uncover some of the secrets interred around and within Wye House. Much of their work is focused on the physical remnants of slavery, which have been obscured by time, vegetation, the slow march of decay. Their digs have unearthed the foundations of slave cabins, charms secreted to ward off spirits in the greenhouse and attics, and the buttons, dishes, broken tools, nails and personal effects discarded, forgotten, and now uncovered.

The Orangery interior, the current site of archaeological investigation by students from the University of Maryland.

Wye House persists, a reminder of the nature of the Chesapeake’s history, at turns both lovely and harrowing. It is our own history, as well as Douglass’ to understand and internalize. The foundations of the country, the Eastern Shore, and Wye House itself were created on the backs of men like Douglass, his family, and his forebearers- a terrible truth, with beautiful, conflicting results nationally, locally, and on a quiet cove on the Wye River. Douglass understood this strange, haunting, captivating quality Wye House possessed. Though it was the place of his enslavement, and was created by a system he spent his adult life trying to destroy, he still said of the house and grounds in his autobiography: "Nevertheless (Wye is) altogether…a most strikingly interesting place, full of life, activity and spirit.”

For more on the ongoing archaeology at Wye House, check out: http://www.aia.umd.edu/

A wonderful resource, “The People of Wye House” compiles all the records of Wye House’s slaves into a searchable database: http://wyehousedb.host-ed.me/

Lost at Sea

From the cemetery at Cold Spring Church.

An article in the New York Times this morning explores the discovery of the Griffin, at 16th century French sailing ship lost in Lake Michigan and its reemergence from the sediments at the bottom of the inland sea. Headed by up a man arguably described as ‘obsessed’, this find has all the makings of a classic treasure hunt story- the devoted but slightly-crazed explorer, a ship full of treasure lost in mysterious circumstances, red tape, international intrigue.

Sunken ships and buried treasure are not sole property of the Great Lakes, or Outer Banks, or the coasts of Maine and Nantucket. The Chesapeake certainly has a slew of her own. Notoriously shallow, shoaled with sand and oysters, and difficult in which to discern bottom soundings, the Bay’s reputation in the 17th and 18th centuries was labyrinthine and deadly.

Scuttled WWI wooden steamship at Mallows Bay, Potomac River. source

According to Don Shomette, who worked for National Geographic in 2011compiling data regarding all known shipwrecks into a map, as many as 2,200 may exist as sand-covered ghosts on the bottom of the Chesapeake’s Bay. His results, published through the National Geographic Press as the Shipwrecks of Delmarva, document the lives and vessels lost forever to the Chesapeake’s capricious tides, wind, and weather. The tiny symbols that thickly pepper the map, each representing a sunken schooner or steamboat, is a reminder that the Bay is a treacherous place, regardless of its placid surface.

Closeup from the Shipwrecks of Delmarva map detailing wrecks at the mouth of the Patapsco River.

While many of the map’s shipwrecks are unidentified, there are plenty of famous wrecks, tantalizingly known and accessible- though the largest challenge to would-be treasure-hunters is the Chesapeake’s notoriously turbid water. Some of the most famous, like the Peggy Stewart, are also made memorable by the fantastic stories of their demise (burned by the owner to quell an angry mob, in that case). But even the less spectacular wrecks are getting attention, thanks to modern methods of bottom sleuthing, like side scan sonar. Amateur underwater archaeologists and hobbyist shipwreck seekers can combine historic charts and state-of-the-art technology to uncover vessels long obscured by thick black sediment, as exemplified by a recent post on Shawn Kimbro’s blog, Chesapeake Light Tackle.

Image from Chesapeake Light Tackle.

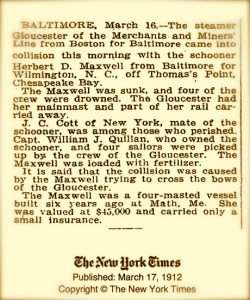

Kimbro dug into the historic background of a known shipwreck off of Sandy Point, the Herbert D. Maxwell. A four-masted schooner bound for Maine with a cargo of fertilizer, she was sunk initially in a 1910 collision with the steamer Gloucester that took the lives of four men. She was sunk again (or rather, deeper) by the US Army Corps of Engineers 1912, as her masts and other wreckage were blocking the shipping channel. Since then, she’s faded from view and memory, until resurrected in a series of spectral images by Kimbro’s side scan sonar unit.

Images from Chesapeake Light Tackle.

Like sepia photos in a shoebox, or discovering your grandma’s cache of cigarettes in a 30-year-old raincoat, these scans are tangible connections with a past that, as Faulkner once said, “is not even past.” It’s what makes them so fascinating- and in general, why we are so interested in shipwrecks. Time capsules, buried by sediment and protected the same water that ultimately drowned them, these vessels powered by steam, sail, and oar linger in brackish purgatory. Their treasure is rarely gold- more often, it’s detritus of a distinctly human scale- ivory toothbrush handles, copper coins, pierced lanterns, nails, canteens, and dice. They wait, lurk, dinosaur bones of a bygone era. Often nameless, these shipwrecks contour the Chesapeake’s bottom by the thousands- which means though many can claim knowledge of their whereabouts, the fresh excitement of new discovery is yours for the taking. All you need, it seems, is a decent depth-finder.

Pleasure House Oysters

This week’s post comes courtesy of Julie Qiu, author, photographer, and oyster connoisseur over at inahalfshell.com on Pleasure House oysters, an aquaculture brand from the Lynnhaven River in Virginia. This year alone, Virginia’s aquaculture industry has produced 28 million oysters- an incredible amount that underscores Virginia’s traditional pro-lease oyster culture and their future as a heavy-hitting oyster producing state. A growing number of discerning consumers like Julie are interested in the provenance of their oysters, which is a good thing for aquaculture ventures like the Ludford Brothers, producers of the Pleasure House oyster. These small companies can capitalize on their oyster-farm-to-table business model, which has never been more popular than in today’s slow food movement. It’s a win for oysters, for oyster farms, for oyster lovers, and for the future of the Chesapeake Bay’s unique culture and environment.

A hefty box of Pleasure House Oysters from Lynnhaven, Virginia were dropped off at my office in Times Square. Little did I know these were a modern day homage to a historically iconic oyster. I shared them with a select group of the most avid oyster loving colleagues, and here’s what we had to say…

The verdict was unanimous: Pleasure House Oysters are amazing. Everyone who tried an oyster most certainly wandered back for a second… and third… maybe a forth, accompanied by big wide puppy eyes. No one could get enough of these supremely plump and toothsome oysters from the great Lynnhaven River.

Back in their heyday, Lynnhaven Oysters were requested by the rich and the royal during the 18th and 19th centuries. European elites loved them for their taste, texture, and tremendous size. Unfortunately over-harvesting and pollution rapidly deteriorated the water quality, and decimated the oyster population along with it. In recent years, there has been a turnaround in the area’s productivity thanks to rigorous water conservation efforts. So much so that the areas where Pleasure House Oysters grow are still occasionally closed for safety reasons*. Fortunately, I had the opportunity to taste Chris Ludford’s oysters in their peak condition back in March.

The Pleasure House brand was created by the Ludford Brothers, who have been growing their own since 2010 as a method of quality control. They care for their oysters by hand from start to finish, only using a motor boat to get them to and from the farm. Talk about a sustainable and artisan product!

But let’s pause for a minute and talk about the name. I mean, I’ve come across some pretty saucy names in my day (i.e. The Forbidden Oyster, Naked Cowboy Oysters, French Kiss…etc), but when I received that first email from Chris, I definitely raised an eyebrow. Here’s the scoop, straight from the creator:

The name of our oysters is a reference to the proximity of our farm to Pleasure House Creek and Pleasure House Point which are both on the Lynnhaven River. The area was settled in 1635 and not long after a tavern was opened on what is now Pleasure House Road which is also near all of the previously named locations. It had no other name other than The Pleasure House. There are many rumors as to what could be found at this tavern from 1700 through the late 1800s but the only facts that are widely accepted point to it as one of the first taverns in the New World where spirits could be had. During the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 it was used by the British and Americans (respectively) as a base and observation point for nearby enemy shipping traffic on the Chesapeake Bay entrance. Unfortunately the structure burned in the 1980′s and has been lost forever.

So there you have it. These oysters are now forever tied (in my mind) to the unimaginable debauchery that was had back then. Their type of fun probably made Gatsby parties look like kids play. Either way, it’s quite provocative and exciting. As a brand strategist, I applaud this level of storytelling. I think it’s a smart way to reel the consumer in and have them associate you with an interesting idea. But of course, branding and marketing isn’t everything. Now it was time to see for myself what they were all about.

The shells were hearty and solid, which made them easy to open without much crumbling. One of my favorite moments when I’m shucking an oyster is hearing and feeling the unlocking of the hinge. It’s like opening a icy can of beer on a hot summer day or popping the cork off a fine bottle of champagne.

The meat, as you can see from the photos, was superbly plump and white. The oyster bellies bulged from their shells, which still contained a great deal of clear oyster liquor. No mud, no grit, and no oyster crabs either.

Tilting the bill of the shell to my lips, I sipped the chilled oyster liquor. It was smooth and had a well-balanced medium salinity that tasted fresh and lively. Next, I slurped the oyster back and chewed carefully. The first sensation that I felt was a sensory awakening. These were extremely clean and crisp oysters! Harvested merely 24 hours before, I could feel the vivaciousness in the flesh.

They were quite plush and varied in mouthfeel. Some bits were as elastic as a clam, while others were soft and supple like sea urchin. I’m a huge fan of interesting texture, and these definitely had it. The flavor was a brothy mix of vegetal flavors: soybean, seaweed, and subtle grassy notes rose to the top. The sweetness was subtle, but rose in force near the finish. The more you eat, the sweeter they seemed to taste.

Overall, Pleasure House Oysters delivered a wonderfully pleasurable experience for me and my colleagues. I hope to see them soon on oyster menues around the city.

*A Side Note: In April, I was informed that the river had a large part shut down for harvest and Pleasure House Oysters was part of it. The oysters that I consumed were perfectly safe, free of contaminants. This closure was the result of, “a general degradation of water quality” as put by the Virginia Department of Health. The readings of poor water quality stemmed from an abnormally wet February and March. Pleasure House Oyster farm had the lowest readings in the closed area and was unfortunately just barely inside the closed area by about 750 yards! Anyway, they are well on their way to reopen at the beginning of June.

All photographs courtesy of Julie Qiu. Check out the rest of her posts on in a half shell but be prepared- they’ll make you hungry!

Underwater Meadows

Widgeon grass. Photos in this post courtesy of chesapeakebay.net

Below the waves of the Chesapeake Bay, trillions of tiny life forces are moving. They flash translucent fins, their claws snap at passing minnows. They creep from their white shells and unfold their feet, waving at passing morsels of plankton. They release a whoosh of water, and with it, a smoke ring of sediment. Although each takes a different shape, these oyster, fish, crab, snail, mussel, and barnacle residents of the Bay proper all have something in common- they are breathing. Their hearts beat their blue or black foreign blood, and tiny lungs force oxygen out of their atmosphere of brackish water and swirling sand. The source of much of this essential element is all around, waving in rhythm with the ceaseless currents: grasses. Dense underwater meadows throughout the Bay are steadily taking in carbon dioxide, sunlight, and nutrients, and releasing oxygen’s breath of vitality into the surrounding waters.

Grasses in the shallows off of Poplar Island.

There is much talk about these grasses today, due to their integral role in the balance of the Bay’s equilibrium. This submerged aquatic vegetation (or SAV for short) supplies not only oxygen, but food, habitat, and tidal buffers for the myriad residents that populate their green, verdant kingdom. Like trees in a forest, SAV in the Chesapeake shape their environment and the animals that have adapted to dwell symbiotically under their protective canopy. Where the grass grows, the Chesapeake’s animal populations thrive and the water slows, dropping sediment and gaining clarity. But when those meadows shrink, the bottom of the Bay becomes a cloudy wasteland of unproductive mud. Without Bay grasses, crabs lose their spawning grounds, migratory waterfowl go hungry, perch gasp for air, and waders at the water’s edge lose sight of their toes once their knees get wet. SAV have a huge impact on the health of the Chesapeake- quite a feat for something that seems so easy to ignore.

A carp peeks from a carpet of bottom grasses.

Knowing this, it seems no surprise that as the Chesapeake Bay grasses decline for the third year, so too has the population of the Bay’s blue crabs. The Baltimore Sun reports:

“An aerial survey flown from late spring to early fall last year found 48,191 acres of submerged vegetation, down 21 percent from the extent of grasses seen in 2011, according to scientists from Maryland and Virginia.

It was the third straight year of reported declines, following a 21 percent drop in 2011 and a 7 percent dip in 2010. Since hitting a peak of sorts in 2009, the bay’s grasses have shrunk to a level last seen in 1986, shortly after scientists began conducting annual surveys of the bay’s grasses.

Scientists attributed the losses in large part to an extended run of unfavorable weather, with extreme summer heat in 2010 killing off lower bay grasses and heavy rains and tropical storms knocking back vegetation in the upper and middle bays. Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee flushed millions of tons of sediment down the Susquehanna and other rivers, turning the bay murky brown for months afterward.”

A crab in the grass.

For blue crabs, the loss of Bay grasses has been a severe blow. Underwater meadows provide food and shelter for crab during the summer, when the courtship and reproductive season are well underway. But summer is also a time when grasses are particularly susceptible to the warm-weather algal blooms, which block sunlight and stunt the growth of the grass beds. Nutrients from septic tanks, from farm fields and pastures, and from car exhaust that have collected in the Chesapeake’s tributaries throughout the spring encourage the growth of these malignant blooms, which expand with oily rapidity as temperatures rise. On the Bay’s bottom, shaded over, the oxygen-producing grasses wither, leaving blue crabs homeless and focused on survival rather than romance.

It’s a vicious cycle, but one that reminds us how deeply and irrevocably interconnected the Chesapeake’s life forms are. For a healthy Bay, one that is productive, clear, and vibrant, we must look to maintain the lawn. Not the clipped, manicured kind in our yards, stretching to the water’s edge, but the kind down below the waves, with roots in the Chesapeake’s sandy bottom where the crab couples hide to find some privacy.

Want to track the rise and fall of Chesapeake grasses over time? Check out this AMAZING time-lapse interactive map, over at the Chesapeake Bay Program:

Not Your Grandma's Tea Party

It’s when the first raft disintegrates; dumping its cargo of flamboyantly-costumed rowers unceremoniously into the tea-tinted water of the Chester River, that you know for sure this isn’t your grandmother’s tea party. The thronging crowd along the shoreline roars in support, cheering the homemade rafts as they smoke, wobble, paddle, perambulate, and yes, even, fall apart, along the length of their route out from Wilmer Park, around a buoy, and back again to the soft mud of the shoreline.

Photo courtesy of chestertownteaparty.org

Shoes, wigs, and even a few rogue beer cans float on the river’s surface, while some rafts sink and others row to victory. All for the promise and bragging rights of a trophy proclaiming their status as “Fabulous Flotsam,” or to achieve the distinction of “Da Vinci,” “Van Gogh,” or the “Junior Cup,” raft race contenders vie for glory. Greatness can be earned through spectacular failure as “the Flop” or through overall prowess as winners of coveted (and elusive) “Tea Cup.”

Raft Race 2012 featured a life-sized replica of the Delorean from Back to the Future called (of course), “Raft to the Future.” Author’s husband as Marty McFly, author’s sister as his time-travelling girlfriend, Jennifer.

It’s Raft Race- an annual event that truly reflects Chestertown’s longstanding history since the 18th century as a maritime refuge for eccentric, irreverent and fun-loving folk. It’s simply one of the best things, and also one of the oddest things, that Chestertonians do.

Photo courtesy of bstar at flickr.com

Held on the Sunday of Tea Party weekend each year (Memorial Day weekend to you), the premise is simple: build a raft of non-nautical materials that can carry at least four people. No engines, no boat parts, and at least half of the competitor’s bodies must be above the water. A few other safety concerns are ticked off, and what you now have are blank canvases for artistic expression, engineering marvels, and personal quirks that seem more akin to Burning Man than the Chesapeake tidewater.

Photo courtesy of chestertownteaparty.org

Rafts from the past have been built to look like full-sized giraffes with safari guides inside, the A-Team with a replica of their GMC Vendura Van (complete with mohawks and medallions), a giant butterfly, a pirate ship overtaken in a male ballerina mutiny, and those were just the ones that floated. Many more have succumbed to the yoo-hoo-colored waves of the Chester due to faulty construction, half-baked propulsion, or hubristic flights of awkward and unwieldy fancy. But in the end, everyone who enters the raft race wins, even if they were passed over for a trophy. It’s an event that’s about embracing the kids and adults that participate, supporting your local community, and letting your freak flag fly high and proud. It’s just enough to make a person patriotic.

2012 winners of the Tea Cup celebrate their victory.

This year’s Raft Race will be held Sunday, May 26th, 2013. Want to see the spectacle with your own two eyes? Check out the schedule for Chestertown’s Tea Party weekend events here: http://www.chestertownteaparty.org/?page_id=131

Chesapeake Spring's Most Savory Species

Often, staff at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum are tapped for information on Chesapeake history, culture, or the environment. What follows is an op-ed written by the author of this blog for the Bay Journal News Service expressing her personal opinion on the historic shad fishery. Learn more about the Bay Journal News Service here or read the original article as it appeared in Southern Maryland Online: http://bit.ly/15KXDp9

Shad fisherman, early 20th century. Courtesy of shorpy.com

Environmental Commentary by Kate Livie

Alosa sapidissima––the American Shad. In Latin, its name translates to “most savory herring,” yet the shad’s exquisite flavor so craved by Chesapeake people for thousands of years is unknown to most folks in today’s watershed. For millennia, as March howled away leaving April in its wake, our ancestors hungrily anticipated the signs that would indicate the spring shad spawn had arrived, with its rich filets and roe, meaty and restorative. Access to the seething hordes of shad, a water-borne salvation after the starving winter months, was so hotly contested that early denizens of the estuary burned, plundered and murdered over the fishing rights.

That annual ritual of springtime feasting was stopped by the widespread proliferation of dams, first for milling, then for electricity, that barred upriver passage for millions of north-bound shad. Today, there is no shad harvest of any consequence in the Chesapeake. Our scrambled eggs in Maryland and Virginia are unadorned by the shad’s savory roe, herald of springtime in the Bay.

Meanwhile, our estuary lost a vital life force that once pulsed through its tributaries signaling rebirth, renewal and survival. We, the inhabitants of the Chesapeake watershed both bipedal and finned, are dammed.

Marshall Hall Shad Planking, 1893. Courtesy of shorpy.com

Shad are anadromous fish that spend most of their lives in the ocean, returning by the millions to spawn in freshwater tributaries once the water temperature warms. This springtime inundation historically defined the bitter edge of winter in the Chesapeake. Indians developed techniques to harness this raging abundance, constructing nets and weirs to corral the frenzied, thrashing shad. After settlement, shad were so ubiquitous in colonial communities that they were distributed to paupers (gaining them the nickname “the poor man’s salmon”).

Shad was also the first fish exported from the Chesapeake in large numbers. Pickled in salt and packed in barrels, shad could be found from the mid-1700s in major city markets like Philadelphia and New York. An early spring shad run has even been attributed to the survival of American troops at Valley Forge during the late winter. That tale (though probably apocryphal), along with the creation of large-scale shad fisheries at the Virginia estates of Washington and other prominent statesmen, cemented shad’s status as the “first fish.” One hundred years before crabs, oysters, or rockfish were established as large-scale fisheries, shad were the most important seasonal harvest in the Chesapeake.

“The Washington Navy-Yard, with Shad Fishers in the Foreground”, Harper’s Weekly April 20, 1861.

Today, the traditional shad fishery has been shut down, leaving only the scanty few caught as commercially regulated bycatch, or through recreational catch-and-release. Prevented from continuing their migration by ever-multiplying dams—the modern Susquehanna watershed alone has 19—the shad population’s precipitous decline began in the early 20th century. Overharvesting quickly followed, as commercial pressure to maintain the fishery took its toll on the dwindling shad schools. As a remedy, generations of human-raised shad were released, only to be obstructed by dams where few of the shad managed to navigate fish ladders or lifts. Within 100 years, the silvery shad that had flooded in numbers beyond catching—beyond counting,—were reduced to a thin trickle weeping through cracks in our barricaded Bay. In 1980, Maryland enacted a moratorium on the shad fishery. Virginia followed in 1993.

The solution to this tragic tale may be in our past. Beginning in the 18th century, Susquehanna access to shad created a series of conflicts so regular they were termed the “Shad Wars.” Documented in scores of legal cases over the next 100 years, river dwellers broke dams, raided, burned, and in some cases, murdered each other for fishing rights. Shad was seen as a birthright, and it represented the difference between poverty and solvency, starvation and plenty. Our Chesapeake forbearers, unlike us, were anything but complacent about their rights to a Bay, commonly owned, whose balance and productivity meant survival.

The modern Conowingo Dam, the largest obstruction today on the formerly shad-rich Susquehanna.

To restore the iconic Chesapeake shad, we must clamor unequivocally for an unobstructed estuary. While some small effort has been made to create fish ladders or passages, the results are sadly inadequate. Many existing dams are outmoded or abandoned and could be easily breached, allowing access. By advocating for an unimpeded Bay, we make a stand for the culture, the fishery, the economy and the natural equilibrium of a Chesapeake Bay—a place where shad have meant spring and renewal for millennia or more.

Kate Livie writes from Chestertown, Md. Distributed by Bay Journal News Service.

Just a Little Bit Better

Oyster tin collection, Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum

Whenever leading a tour of our Oystering on the Chesapeake exhibit, I never fail to stop at the wall of oyster cans so everyone can take a good look. Candy-colored and eye-assaulting, each tin jabs visual elbows with its neighbor, fighting to be noticed among a riot of text and imagery that present a collective homage to Chesapeake capitalism. The sheer diversity of the cans, each insisting on the superiority of their brand’s freshness, cleanliness, purity, location of origin, and taste, makes the answer to my question harder than you would think: “Are the contents of these cans different, or all they all the same?”

“Just a Little Better”: Cans from the oyster packing house that once occupied the Museum’s grounds in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Coulbourn and Jewett.

Of course, each can contained Chesapeake oysters, whose variances in taste were imperceptible to the average palate. But to the 19th century consumer, perusing a shelf where competing brands lined up like soldiers in a battle for attention, those visual indicators shouting every possible difference would have been highly persuasive. Even today, when we modern, world-weary shopping sophisticates are presented with a panoply of oyster cans, it can be hard to tell that only the splendid exteriors deviate from their slick, briny sameness inside.

When most of the cans in the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum were produced, marketing was anything but the constant barrage of pictures, sounds, and slogans we 21st century denizens absorb. It was the late 19th century, and for the first time in history, images (of any kind, even the most humble) were available widely to the public. Just 50 years earlier, most Bay folks would have possessed only a few books, and most of those were unillustrated. Newspapers and signage were comprised of forests of unrelieved inky text. The ghostly results of early photography had yet to be invented, and paintings were generally owned by only the rich. Thanks to the wonders of the industrial age, however, that all quickly changed as advances were in made in technology that could reproduce pictures en masse, on a myriad of mediums.

Examples of artwork, logos, slogans and photography used by oyster packing houses to shill their products from the collections of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Canning itself was a new novel technique, also produced by innovation during the Industrial Revolution. Prior to its invention in early 19th century France, food had to be dried, salted, or pickled to maintain freshness. Although recipes for pickled oysters existed, it isn’t hard to imagine why they would have never truly tickled the fancy of American oyster consumers, accustomed as they were to fresh shellfish that tasted of the sea rather than of vinegar. So oysters, isolated from a larger market their quick spoilage, remained a slow and local seafood economy for most of the Chesapeake until the wonders of canning made them widely available. Distributed in iced refrigerated cars, the garishly cheerful Chesapeake oyster cans traveled far from home across the spiderweb network of train tracks to destinations as far-flung as Colorado, Kansas, and even Australia.