For most people these days, if you spend any time on the Bay, it’s usually to relax. Kayaking, sailing, taking the kids out for a day on Conquest Beach in your motorboat with a cooler of drinks and sandwiches, fishing off the town dock. Watch the sun set, enjoy the view, that sort of thing. Serene, fun.

This is a purely modern approach towards our watershed, though, when you compare the present to the Bay’s tumultuous past. It’s hard to conceive of the Chesapeake being a place where you literally risked your hide for access to its resources or land. But from plenty of historical accounts, we can see that it was anything but serene.

A perfect example of the life-or-death history of the Chesapeake is the ‘seasoning’ time of the 17th century, where you either survived virulent bouts of malaria and were considered 'seasoned’, or you summarily kicked the bucket, and were therefore 'unseasoned’. Seasoning was a risky prospect, but as with many of the foolhardy, ignorant, or rash decisions made by many colonists bound for different parts of the New World in the 17th century, it was considered to be the price of admission for a part of the land rush in the New World. The Chesapeake’s price, though, turned out to be mighty steep.

This skeleton, courtesy of Smithsonian’s 'Spelled in Bones’ exhibit, clearly 'unseasoned’.

Immigrants from England expected the seasoning process, and letters from new colonists reflect commonplace nature of the illness. William Fitzhugh wrote in 1687 that his sister, a new Virginia resident, had experienced, “two or three small fits of fever and ague, which has now left her, and so consequently her seasoning [is] over.”

Although bouts of 'seasoning’ were commonplace and frequently fatal, very little was known about it at the time. Mostly differentiated from other ailments by a very high body termperature, malaria in those days was commonly referred to as “ague” (pronounced 'egg yoo’), a general term for fever. The cause was attributed to bad air (in Italian, literally mal aria), and Chesapeake residents were especially wary of exposure to the torpid humidity of the Bay’s marshes and swamps in September and October, when cases of ague peaked.

Now we know that seasonality reflects the life and breeding cycle of the malarial carriers, mosquitoes. But then, colonists feared the very indian summer air they breathed, terrified of a death like Landon Carter’s daughter Sukey suffered in 1758: “-her face, feet and hands are all cold and her pulse quite gone and reduced to the bones and skin that can cover them and dying very hard- severe stroke indeed to A Man bereft of a Wife and in the decline of life.” Sukey was only 7.

For 35 to 40 percent of Chesapeake population to come down with malaria, this was the consequence of the 'seasoning period’: agonizing death over several days, prefaced by intensifying cycles of raging fever, drenching sweats, and violent chills. For those who survived seasoning, relapses were common, in addition to a weakened immune system that was susceptible to a host of other horrible-sounding ailments: the “bloody flux”, “bilious fever” and the disturbingly vague “swellings”.

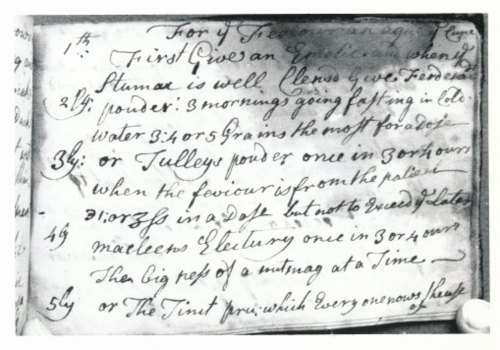

Attempts at treatment sound similarly awful. In this 18th century document titled, “Ye Fever, an Ague, ye Cure,” fasting, emetics, and vomiting are prescribed for the ailing patient (read full transcription here: http://bit.ly/vcqGG7). All this, if you survived, for a life of expectancy of about 45 years for a man, and 4 to 8 years less for a woman.

So the next time you watch the sunset over the Chesapeake, ice tinkling in your glass, ask yourself: would you risk it? Risk fever and chills, 'swellings’ and agony, for a chance to make a new start? And then take another sip of your gin and tonic and enjoy the fact that you don’t have to.

* I relied on a few great resources for this piece that I’d like to acknowledge: “Ague and Seasoning” by Robert T. Whitlock, M.D., from CBMM’s periodical, The Weather Gauge, and “Living and Dying on the 17th Century Patuxent Frontier” by Julia A. King and Douglas H. Ulbelaker, available to read online at the Jefferson Patterson Park website here: http://bit.ly/s5TJx9