Harper's Weekly illustration of a Baltimore packinghouse, March, 1872. Collection of author.

Oystering in the 19th century was a nasty business. Shellfish harvests were highly competitive, prices were high, and little heed was paid to harvesting regulations (or the Oyster Navy enforcing them). People killed over access to oysters and the money they represented, and whether that meant a oysterman murdering an immigrant crewmember or a tonger gunning down a rival skipjack captain, anarchy prevailed. By the late 1800's, oyster poaching and general lawlessness was rampant on the Bay's byways- all to feed the ceaseless demand of the oyster packinghouses in Baltimore, Crisfield, Solomons, and Norfolk. In each city, hundreds of packinghouses competed for dock space and consumer adoration, turning out hundreds of thousands of cans from each brand every year. Transported by rail, these cans of Chesapeake oysters brought the brackish taste of the Bay to hungry Americans across the country, in communities thousands of miles away from the coast.

Oyster shuckers, Rock Point, Maryland. Image from the Library of Congress collections.

Oyster packinghouses, although far less likely to incite murder, were another often unsavory link in the processing chain that moved oyster from the Bay to markets across the country. As the image above shows, these were wet, dark, cold places where oysters were shucked, packed and shipped by an immigrant or African-American workforce. An industrial report in 1886 described the workers in one of Baltimore's 45 packinghouses: " The oyster shuckers are a vert hard working, good-tempered- if not very clean- community; their morals are not very strict, if their conversation is a criterion, and the standards of intelligence is certainly low." The reporter went on to state the average wage for one of these maligned workers- a paltry 5 cents per can.

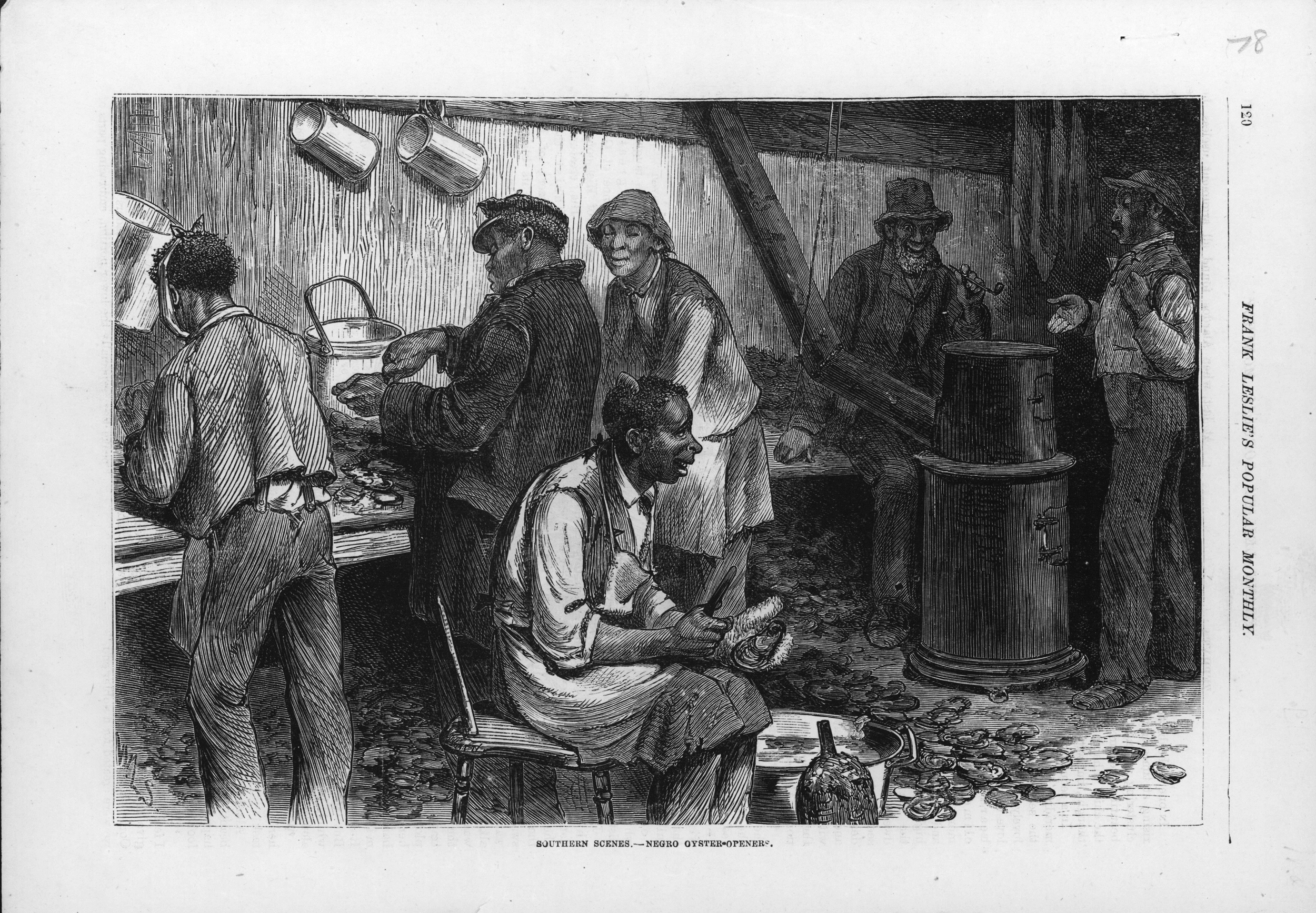

Image of a crisfield packinghouse, Frank Leslie's Weekly, 1878. Collection of Author.

Crisfield, Maryland's packinghouses were largely supplied by African-American labor, unlike Baltimore, where German and Irish immigrants made up the majority of the workforce. Many of these shuckers, washers, blowers, measurers, and fillers were once slaves who now toiled for nominal wages at the town's 16 different packinghouses. In 1880, one report estimated that out of 678 employees working for oyster packers in Crisfield, 500 of those were African-American. Together, these shuckers had packed 427,270 bushels of oysters in a single year.

"Little Lottie, a regular oyster shucker", by Lewis Hine, 1911. Library of Congress Collections.

Children frequently worked alongside their parents in the gritty, steamy packinghouses, shucking oysters while standing on drifts of slowly rotting shells. It was a frequent sight in the era prior to child labor laws, and a reminder that like New England's mills or West Virginia's coal mines, oyster packinghouses were one part of the vast Industrial Revolution that ground along on human cogs. Indeed, Thomas Kensett, one of the founders of Baltimore's oyster canning industry, proudly stated in 1869, "Were it not for the shucking of oysters, many children, from twelve to fifteen years of age, would spend much of their time in the streets and around the wharves and docks, being trained up to immorality and crime, and preparing to fill up our jails and warehouses."

A Baltimore worker individually solders the oyster cans before shipping. Harper's Weekly, 1872.

For 60 years, packinghouses were the lifeblood of the Chesapeake's waterfront communities. Even small towns might have one that packed tomatoes in summer, and oysters in winter, or later when the oyster harvest declined, transitioned to picking and packing crabmeat.

Today, all but a notable handful of these packinghouses are gone, and the few that are left often employ a combination of locals with an influx of immigrants from Central America on H2B visas. JM Clayton's in Cambridge, Metompkin in Crisfield, Chesapeake Landing in St Michaels- these businesses have managed to survive even as their traditional workforce has moved on to jobs with benefits, salaries and indoor heating, and as the Chesapeake oyster industry has plummeted and started to rise again. Despite these changes, much remains the same for the Bay's remaining oyster packinghouses. It is still dirty work, it is still a job where shuckers get paid by the pound, and one where English is still intermingled with many different languages- all down a long packing table where oysters are shucked by deft hands, faster than the eye can see.